Of the 243 people who invested money in 1824 to finance the construction of the Thames Tunnel, only eight were women. Five of these eight were sisters.

In this blog, Jack Hayes uncovers the story of the five orphaned sisters who invested in the Thames Tunnel Company. Shrewd international businesswomen from Rotherhithe, the sisters navigated financial markets of the 1820s with confidence. Their story provides an insight into the types of people, women as much as men, who funded the construction of the world’s first tunnel under a navigable river.

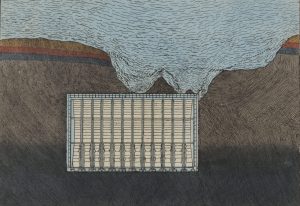

View of the tunnelling shield showing effects of flooding, 1827. Possibly attributable to Joseph Pinchback. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.24

If you were looking to make a profit in early nineteenth-century London, buying shares in the Thames Tunnel Company wasn’t a good idea.

In 1828, as the project faltered under the pressure of flooding and the Company attempted to raise more capital,, an anonymous shareholder printed a letter, criticizing failures and lamenting the poor chance of a return:

What prospect have we of being remunerated for any further outlay? Our original capital is sunk and gone, and in the present state of the Tunnel we can get no return for it.[1]

Modern studies have assumed the anonymous author of this letter to be male.[2] Why? This was not an assumption made by those who drafted the Thames Tunnel Company Act 1824, which clearly acknowledges the existence of female shareholders.[3]

Still, only eight of the 243 people who invested money in 1824 to finance the construction of the Thames Tunnel were women, around 3% of the total.[4] All are largely unknown. Glancing down the list of investors, however, one feature is immediately evident: three of the named women have the same surname. In fact, further investigation reveals a total of five sisters, all of whom held shares in the Thames Tunnel Company in their own right.[5]

Why did five sisters invest together in Marc Brunel’s Thames Tunnel? What led them to put their money at risk in a project whose aim was to build a tunnel beneath a river, an endeavour which had failed twice before in the previous twenty years?[6]

By tracking what is known about their lives and careers, and reading it alongside a growing body of research into women investors in the 1800s, the sisters come to light as capable and sometimes wily financial operators. For them, the Thames Tunnel represented just one of many business interests.

I do hereby give and bequeath all my property unto my five daughters

On 17 June 1818, Daniel Meilan, a merchant of Dutch descent, died aged 82 in London.[7] Meilan had been very successful since the 1760s as a member of the East India Company and a merchant working between the Netherlands and London.[8] Engaged in his local communities, he served variously at as both Elder and Deacon at London’s Dutch Church, located next door to his City offices in Austin Friars; and gave often to charitable causes, especially after he became a widower in 1803.[9] Little is known about Meilan’s family life; however, his family were clearly wealthy and well-connected. A composition by pianist to the Prince Regent, Jean Théodore Latour (1766-1837), and dedicated to two of Meilan’s daughters around the date of their mother’s death, implies the family moved amongst fairly elite social circles.[10]

The Dutch Church, London, 2024. The original building was destroyed in World War II, and rebuilt in the 1950s

On Daniel Meilan’s death, his five unmarried daughters – Ann (1784-1840), Frances (1785-1839), Sophia (1787-1836), Louisa (1792-1848), and Amelia (1795-1887) – became orphans. In a will drawn up two months earlier, their father had divided his entire estate equally amongst the five women.[11] The sisters now had to take control of the money for themselves.

In the first instance, two sisters continued their father’s business, operating between London and the Netherlands just as he had. In 1819, Sophia and Frances Meilan signed a contract with their father’s former business partner Jabez Exsham, and the young Dutch nobleman and politician, Gustaaf Willem van der Feltz (1793-1870).[12] The following year, the sisters were importing goods directly from Rotterdam into London.[13]

In 1820, Frances Meilan married Nicolaas Warin (1776-1843), a Dutch merchant.[14] Two years later, in 1822, Sophia married Thomas Wilkinson (c. 1770-1840), a banker.[15] Under English law married women faced restrictions on their freedom to deal with finances and own property.[16] As such, while one record perhaps implies the sisters retained the odd client, as a general rule Sophia and Frances Meilan disappear from financial or commercial records after their marriages.[17]

‘Spinsters, all of London’, and International Businesswomen

In 1813, the narrator of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice – a novel that charts the fortunes or, perhaps, the potential fortunes, of five daughters – could famously declare it a ‘truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife’.[18] It did not stand to reason, however, that a single woman in possession of a good fortune must necessarily be in want of a husband, since unmarried women had more financial freedom than wives.

The Great Hall, Bank of England. Thomas Rowlandson, after John Hill, 1808. Smithsonian Design Museum, Washington, D.C. 1961-505-230

Luckily for the Meilan family business, three sisters, Ann, Louisa, and Amelia, remained unmarried and took up the mantle. The trio operated much as their sisters and father before them, acting as financial agents or brokers. They dealt particularly in consolidated annuities – so-called ‘consols’, akin to modern government bonds – held by clients in the Netherlands at the Bank of England. This was a big business. Claims of dividends from, or transfers of, consols had to be made in person at the Bank in London.[19] At the end of the 1700s, 85% of all foreign holders of British consols had been Dutch and over 50% of Dutch capital invested abroad had been invested in England.[20] Though Dutch clients’ share of the English market gradually declined, and though the Dutch government attempted to ban overseas investment between 1816-24, in the 1820s there were still many people who required London brokers to claim payments or to trade on their behalf.[21]

Document nominating Ann, Louisa, and Amelia Meilan as financial brokers of Dutch clients, 7 October 1823. Nord-Hollands Archief, Haarlem, Notariële protocollen en akten van notarissen te Haarlem, 1617/90/1743, fol. 783r.

The sisters’ clients included the royal physician and professor Josephus Chrisostomus Bernardus Bernard (1774-1852); the newspaper editor and printer of Dutch banknotes, Johannes Enschedé III (1785-1866); and the mayor of Haarlem, David Hoeufft (1762-1836).[22] All former clients of their father, they were retained by the sisters for at least a decade.[23] Despite the Bank of England’s efforts, fraudulent brokers posed a key risk to investors in this period.[24] That these influential men entrusted the sisters to act on their behalf thus implies a high degree of certainty that they were competent and trustworthy.

The sisters’ international business also made them privileged conduits of news and information across the North Sea; they appear as intermediaries in advertisements seeking missing Dutchmen in British newspapers.[25] Beyond the purely altruistic, these notices sometimes served to identify heirs who would require the sisters’ financial services.[26]

As well as being capable agents with high-profile clients, the sisters deftly navigated the legal intricacies of business partnerships. Around 1822, they were joined in partnership by their new brother-in-law, Thomas Wilkinson. Wilkinson did not have a stellar track record, having previously been involved alongside his father and two others in a bank which collapsed somewhat spectacularly in 1809.[27] In the early 1820s, he was engaged in another banking partnership which also collapsed, with Wilkinson being declared bankrupt in 1825.[28]

The Meilan sisters, however, had planned ahead. Four days before Wilkinson was declared bankrupt, the partnership with his sisters-in-law had been terminated.[29] This shrewd move avoided saddling the women with any liability for Wilkinson’s debts, guaranteeing their financial stability. The sisters then continued in partnership together. They were later joined by another of their father’s former colleagues, eventually entrusting the business to him in 1836 when two of the sisters began to grow ill.[30]

Alongside their work as financial agents, the five sisters began to invest. Given their client work, this is unsurprising: the sisters were manifestly comfortable navigating and negotiating financial transactions of this sort. In 1820s London, prospective investors had various options, and the sisters followed in a long line of women investors, active since the emergence of modern capital markets in England around the end of the 1600s.[31]

Even before her father’s death, Ann Meilan had purchased a Naval Annuity (the so-called ‘Navy 5 per cent’), a short-lived but very popular financial instrument used to fund the Royal Navy, which offered a high 5% return.[32] Within about a decade of their father’s death, the sisters held £1,000 in such annuities, alongside other investments worth some £15,000.[33] In the context of early nineteenth-century London, their holdings made them quite notably wealthy.[34]

Shareholders of the Thames Tunnel Company

As well as buying government debt, the sisters could also invest in private companies. This was not unusual; one study of 151 companies formed between 1780-1851 notes that only 17% of companies had no women investors, clearly suggesting the presenve of women investors was the norm.[35] By the 1830s, a boom in women’s shareholding began.[36]

![Text from an old book - reads: AN ACT FOR Making and maintaining a Tunnel under the River Thames, from some Place in the Parish of Saint John of Wapping, in the County of Middlesex, to the Opposite Shore of the said River, in the Parish of Saint Mary Rotherhithe, in the County of Surrey, with sufficient Approaches thereto. [ROYAL AsSENT, 24th June 1824.]](https://thebrunelmuseum.com/app/uploads/2023/10/investor002-238x300.jpg)

Detail from a copy of The Thames Tunnel Act 1824. Courtesy of the Institution of Civil Engineers, London.

Perhaps, given their knowledge of finances, high-risk investments did not faze them. There was, however, a compelling reason for investing: while operating across increasingly interconnected global financial markets, the Meilan sisters had a clear connection to Rotherhithe.[39] Their grandfather and mother had been born in Rotherhithe, and the family owned property in the area, which in 1818 the five sisters had inherited.[40] The Thames Tunnel, running between Rotherhithe in the south to Wapping in the north, could be very useful.

The towers of the City in 2024, seen from Rotherhithe; the Thames Tunnel runs directly below the this section of river.

Firstly, the Tunnel promised to facilitate the movement of cargo north and south; it would therefore assist their work bringing goods from the Netherlands into and across London. Secondly, it stood to dramatically simplify journeys related to their financial dealings. Setting out from Rotherhithe in the 1820s, the Meilan sisters would have had to take a boat across the river – impossible in poor weather – or a lengthy detour across London Bridge, to reach the Bank of England in the City and make deals on behalf of their overseas clients. With the Thames Tunnel completed, the sisters should have been laughing all the way to the Bank.

While many shareholders had a connection to Marc Brunel, or were engineers, the Meilan sisters’ example emphasizes that wealthy Rotherhithe landowners also participated in the project, perhaps interested in the Tunnel less as a miracle of engineering and more because it promised real, practical benefits.

The five sisters, alongside their brothers-in-law, held a total of 85 shares in the Tunnel Company, valued at £4,250. This amounted to just over 2% of the total funds initially raised to construct the Tunnel. Each woman held 10 shares in her own right, double that of the next largest female shareholder, Ann Roberts (5 shares).[41] Nicolaas Warin likewise held 10 shares, while Thomas Wilkinson purchased 25.[42]

Together, the family’s holdings came close to those of the wealthy Twining family of tea merchants, who held 100 shares at a value of £5,000.[43] This made the Meilan sisters and their brothers-in-law a key shareholder bloc. Indeed, the family’s centrality to the endeavour included one of them – Thomas Wilkinson – becoming one of the first Company Directors; he sat on a committee which dealt with the Company’s finances (though he appears to have done little or nothing, and disappears swiftly from the records following his bankruptcy in 1825).[44]

The Meilan sisters apparently utilized their relationship to male shareholders to important effect, underlining the women’s adroitness in financial dealings and their ability to navigate the societal restrictions placed on them. In this period, proxy voting was the norm for women shareholders.[45] Since the Thames Tunnel Company Act 1824 required that proxies be fellow shareholders, Nicolaas Warin and Thomas Wilkinson would have been convenient choices ensuring the women’s voices as shareholders were heard.[46]

Most pertinently, the sisters also used their male relatives to increase their voting power. In the 1800s, many women’s shares were held for them in trust by a male relative – this was likely the case of the share bought by Marc Brunel for his daughter Emma, but held in the name of her brother, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.[47] As such, the vast majority of women shareholders were unmarried and it is therefore striking to find that the two married sisters, Frances and Sophia, held shares in their own name alongside their husbands.[48]

This, too, was done for a reason: under the 1824 Act, the number of votes each shareholder could cast was capped.[49] By splitting shares between spouses, they benefitted from a larger number of votes, using a tactic often employed by family shareholders to increase voting power.[50] Each sister, and their brother-in-law Nicolaas Warin, received 3 votes for their 10 shares. Thomas Wilkinson received 5 votes for his 25 shares. Had either Frances and Nicolaas or Sophia and Thomas combined their shares, the Meilan family bloc would have received 19 votes (5 votes per couple, plus 3 votes each for the 3 single sisters). By splitting votes among spouses, they benefitted instead from 23 votes (3 votes each for the 5 sisters and Nicolaas, plus 5 votes for Thomas).

‘Spirited’ Women and a ‘Grand Commercial Enterprise’

Artists’ impression of the finished Tunnel, 1836. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.28(b)

The Tunnel was not a good investment, a fact which was probably quickly apparent as the project began to encounter a range of problems. None of the family appear on the list of those who offered further money to the project in 1828.[51] By 1830, following two floods and the suspension of works, their shares in the Tunnel were likely little more than worthless; neither Ann nor Louisa Meilan listed them in their wills drawn up that year.

Though the sisters’ investment in the Thames Tunnel ultimately failed to provide any great income, this did not make much difference to their vast investment portfolios largely focussed on holdings of securities and annuities which promised essentially risk-free steady rates of return. As each in turn died, in 1848 just one sister – Amelia Meilan – was left holding all the land, property, and investments built up by her siblings. Amelia Meilan had no need to work; having inherited everything, in the 1851 census she is listed simply as a ‘fund holder’.[52]

Canon Beck Road in 2024; the buildings behind stand roughly on the site of Amelia Meilan’s Ragged School

She outlived her sisters by quite some way; when she died aged 93 in 1887, the London Illustrated News proclaimed her ‘the last of her generation’, noting that she was well-known for her ‘kind and charitable acts’.[53] Such acts included the 1857 purchase of houses near the Thames Tunnel’s entrance, in what is now Canon Beck Road, ‘for the erection of the Ragged School’ for impoverished children.[54] On her death, Amelia Meilan left an estate valued at over £11,000.[55] Despite poor investment returns on the Thames Tunnel, the Meilan sisters’ business acumen had kept them quite wealthy.

Only two of the five sisters, Louisa and Amelia, lived to see the Thames Tunnel completed. Their brother-in-law, Nicolaas Warin, died on 24 March 1843, just one day before the Tunnel opened to the public.[56] Yet, thanks to their investments, from 25 March 1843 onwards those looking to cross the Thames, for commerce or otherwise, could do so with far greater ease. Though it cannot have seemed likely at the time, the confident prediction of one anonymous shareholder in 1826 would become reality:

Among the numerous projects started by Joint Stock Companies, none appears so likely to transmit to posterity the daring ingenuity of the present generation as the Thames Tunnel […] future generations will, I trust, reap the advantages of the spirited individuals who now direct this grand commercial enterprise.[57]

In 2024, the towers of Canary Wharf, one of the world’s foremost financial districts, can be clearly seen from Rotherhithe, and the Thames Tunnel now carries many of those who work there. While information about the sisters’ business dealings has to be pieced together from brief and broken records, only a small leap of the imagination is required to think these ‘spirited’ women would approve.

With thanks to Kim Boursnell and Simon Brinkley at the Parliamentary Archives (find out more about the move of the Parliamentary Archives to The National Archives in Kew here); and to Marja Kingma at the Dutch Church in London for their generous assistance in accessing and using materials cited here.

References

[1] A Letter to G. H. Wollaston, Esq., Deputy Chairman of the Thames Tunnel Company, on the Present State of the Affairs of the Company, by a Shareholder (London: James Ridgway, 1828), p. 9 (emphasis in the original).

[2] cf. e.g. Derek Portman, The Thames Tunnel: A Business Venture (unpublished MS, 1998), pp. 44-5, online via www.derekportmanhistory.info. On the drive to raise share capital, see pp. 47-96; and Paul Clements, Marc Isambard Brunel, 2nd edn (Chichester: Phillimore & Co., 2006), pp. 98-100.

[3] cf. e.g. Thames Tunnel Company Act 1824 (5 Geo. 4 c. clvi), para. V, which provides that all shareholders ‘shall have a Vote or Votes by himself, herself, or themselves, or his, her, or their Proxy or Proxies’ (my emphasis).

[4] There exist, to my knowledge, three lists of investors. One is provided in the preamble of the Thames Tunnel Company Act 1824 (5 Geo. 4 c. clvi); it gives only names, without enumerating associated shareholdings. Two more detailed manuscript lists were submitted to Parliament and enumerate both shares held and their monetary value: Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/3/plan1824/T2, fols 31r-35r; and HC/CL/PB/6/plan1824/60, fols 2r-3r.

[5] The others are: ‘Miss M. A. Hawes’ (1 share, £50); Sarah Hawes (3 shares, £150); and Ann Roberts (5 shares, £250).

[6] Two previous attempts had been made, the first between Tilbury and Gravesend in 1798-1802 by Ralph Dodd, the second between Rotherhithe and Limehouse in 1805-09 by Robert Vazie and Richard Trevithick. See Graham West, Innovation and the Rise of the Tunnelling Industry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 104-7.

[7] The European Magazine and London Review, vol. 82 (London: James Asperne, 1818), p. 543; Graham Jefcoate, An Ocean of Literature: John Henry Bohte and the Anglo-German Book Trade in the Early Nineteenth Century (Georg Olms Verlag, 2020), p. 233.

[8] For Meilan’s activities between London and the Netherlands, see e.g. University of Nottingham Library, Nottingham, Ne D 629/2 and Ne D 629/3; and Door W. J. de Leur, ‘Anthony en Anthonetta Kuijl en de stichting van Kuijl’s Fundatie’, Rotterdamsche Jaarboek 9.1 (1983), 305-28 (p. 315). For his membership of the East India Company, see A list of the names of the members of the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East-Indies, who appear qualified to vote at their general courts (s.l. [London]: s. n. [East India Company], s.d. [1795]), p. 56.

[9] For Meilan’s activities at the Dutch Church, around the corner from his office in Austin Friars, see The Marriage, Baptismal, and Burial Registers 1571 to 1874, and Monumental Inscriptions, of the Dutch Reformed Church, Austin Friars, London […], ed. by William John Charles Moens (Lymington: ‘Privately Printed’, 1884), pp. 210, 213; and The London Gazette, no. 15572, 2 April 1803 p. 390. For his charitable donations, see e.g. cf. e.g. A List of Members of the Philanthropic Society to 31st of March, 1809 (London: The Philanthropic Society, 1809), p. 31; Account of the Lying-In Charity for Delivering Poor Married Women at their own Habitations (London: S. Gosnell, 1818), p. 57. For the death of his wife, Fanny King, see The Lady’s Magazine or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex […], vol. 34 (London: G. & J. Robinson, 1803), p. 504.

[10] Jean Théodore Latour, A Duet for Two Performers on One Pianoforte, with or wihtout the Additional Keys, in which is introduced the Favorite Air Away with Melancholy. Composed and Dedicated to Miss Meilan and Miss Sophia Meilan (London: Bland & Weller’s, 1803).

[11] The National Archives, London, PROB 11/1607/78 (Will of Daniel Meilan, drawn up 4 June 1818, proved 6 August 1818): ‘I Daniel Meilan of London merchant make this my last Will and do hereby give and bequeath all my Real and personal property of what nature or kind soever unto my five daughters viz. Anne Meilan Frances Meilan Sophia Meilan Louisa Meilan and Amelia Meilan […] officially to be divided between them share and share alike…’

[12] Drenthe Archives, Assen, 0114.03, Doc. 30. For Daniel Meilan and Jabez Exsham’s partnership, see The London Gazette, no. 15554, 29 January 1803, p. 131.

[13] Customs Bills of Entry, Ships Reports, London, 22 August 1820 and 7 September 1820, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool, C/BE/7/LON/1820/Jul-Sep/45.

[14] The European Magazine and London Review, vol. 77 (London: James Asperne, 1820), p. 274. Nicolaas Warin arrived in Britain from the Netherlands in 1804; he was naturalized in 1805, at which stage he presumably also anglicised his name to Nicholas Warin or Waring cf. 45 Geo. III c. liv (‘An Act for Naturalizing Nicholas Warin’, 1805, Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/1/1805/45G3n159); Report from the Select Committee on the Usury Laws ([London]: ‘Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed’, 1818), pp. 41-44.

[15] Galignani’s Messenger, no. 2251, 18 May 1822, fol. 2v. Scant little appears to be known about Wilkinson; see below for some further indications.

[16] David R. Green and Alastair Owens, ‘Gentlewomanly Capitalism? Spinsters, Widows, and Wealth Holding in England and Wales, 1800-1860’, The Economic History Review 56.3 (2003), 510-36 (p. 516); Anne Laurence, Josephine Maltby, and Janette Rutherford, ‘Introduction’, in Women and their Money, 1700-1950. Essays on Women and Finance, ed. by Anne Laurence, Josephine Maltby, and Janette Rutherford (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 1-30 (pp. 5 and 7). Note, however, that in some circumstances these restrictions could be ignored: see Robert J. Bennett, ‘Interpreting Business Partnerships in late Victorian Britain’, The Economic History Review 69.4 (2016), 1199-1227 (p. 1206).

[17] Sophia Meilan’s marriage certificate is pasted into a record of annuities, alongside manuscript marginalia indicating that in 1825 she was ‘one of the attornies to P. van der Boogaart’, who held a £10 annuity: see National Archives, London, NDO 2/49, fol. 93v. He may well be the Pieter Alexander van der Boogaart who, like Sophia’s father, served as deacon and as elder of the Dutch Church (cf. Moens, ed., The Dutch Reformed Church, pp. 210 and 213). He was perhaps retained because he was known personally to Sophia.

[18] Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice: A Novel, 3 vols (London: Printed for T. Egerton, 1813), vol. 1, p. 1.

[19] Green and Owens, ‘Gentlewomanly Capitalism?’, p. 528. Anne L. Murphy, Virtuous Bankers: A Day in the Life of the Eighteenth-Century Bank of England (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023), pp. 105-7 details the Bank’s standard processes for dealing in and transferring consols.

[20] J. F. Wright, ‘The Contribution of Overseas Savings to the Funded National Debt of Great Britain, 1750-1815’, Economic History Review 50.4 (1997), 657-74 (p. 666); Kenneth Morgan, ‘Anglo-Dutch Economic Relations in the Atlantic World’, in Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680-1800. Linking Empires, Bridging Borders, ed. by Gert Oostindie and Jessica V. Roitman (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 119-39 (p. 124). On Dutch money invested in Britain, see also Stefan E. Opers, ‘The Interest Rate Effect of Dutch Money in Eighteenth-Century Britain’, The Journal of Economic History 53.1 (1993), 25-43.

[21] Wright, ‘Overseas Savings’, p. 672; Michael Wintle, An Economic and Social History of the Netherlands, 1800-1920. Demographic, Economic and Social Transition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 99.

[22] See Nieuw Nederlansch Biographisch Woordenboek, ed. by P. J. Blok and P. C. Molhuysen, 10 vols (Leiden: Sijthoff, 1911-37), vol. 4 [1918], pp. 142-3 (Bernard), and 573-4 (Enschedé III); and vol. 7 [1927], pp. 595-6 (Hoeufft).

[23] Nord-Hollands Archief, Haarlem, Notariële protocollen en akten van notarissen te Haarlem, 1617/90/1739, fols 395r-395v (20 September 1815); 1617/90/1743, fols 783r-783v (7 October 1823); and 1617/90/1750, fols 74r-74v (16 April 1833).

[24] Amy M. Froide, Silent Partners. Women as Public Investors during Britain’s Financial Revolution, 1690-1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 151-2; Murphy, Virtuous Bankers, pp. 116-7, 141, 163-4 explores tactics used by the Bank to protect against fraud.

[25] cf. e.g. The Morning Chronicle, 10 March 1821, fol. 1r: ‘If Mr. Gauthier Jean Anne Eckhardt, who was at Bangalore on the 1st March, 1815 […] is living, he is requested to write to his family in Holland […] and if necessary to forward his letters under cover to Messrs. D. Meilan and Co., London’.

[26] cf e.g. Public Ledger, and Daily Advertiser, 13 September 1825, fol. 1r: ‘If Jodocus Casius, of Amsterdam, who went to sea some years since, be still living, and will apply to Messrs. Daniel Meilan & Co. 35, Great Winchester-street, he will hear something to his advantage. If dead, his legal Representative may apply’

[27] See F. G. Hilton Price, A Handbook of London Bankers with Some Account of their Predecessors the Early Goldsmiths, 2nd edn (London: The Leadenhall Press, 1891), pp. 16-7; ‘BLOXAM, Matthew (1744-1822), of Highgate, Mdx. and Morden, Surr.’, History of Parliament, online at: http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1790-1820/member/bloxam-matthew-1744-1822; and National Archives, London, B 3/242-48.

[28] Cobbett’s Weekly Register. Volume LVII. From January to March, 1826 (London: W. Cobbett, 1826), p. 118; The National Archives, London, B 3/4656, B 3/4657, B 3/4658, and B 3/4659.

[29] The London Gazette, no. 18204, 20 December 1825, p. 2332.

[30] The London Gazette, no. 19484, 14 April 1837, p. 986.

[31] On this earlier period, see esp. Froide, Silent Partners; and Murphy, Virtuous Bankers, pp. 99-100.

[32] The Names and Descriptions of the Proprietors of Unclaimed Dividends on Bank Stock, and on all Government Funds and Securities, Transferable at the Bank of England […] (London: Teape and Jones, 1823), p. 452.

[33] The National Archives, London, PROB/11/2083/316 (Will of Louisa Meilan, drawn up 21 May 1830); and PROB/11/1935/102 (Will of Ann Meilan, drawn up 27 May 1830).

[34] Green and Owens (‘Gentlewomanly Capitalism?’, p. 517) note that 93% of women in London in 1830 –the year the sisters drew up their wills – held estates of less than £10,000.

[35] Mark Freeman, Robin Pearson, and James Taylor, ‘Between Madame Bubble and Kitty Lorimer. Women Investors in British and Irish Stock Companies’, in Laurence et al., ed., Women and their Money, pp. 94-114 (p. 102).

[36] Freeman, Pearson, and Taylor, ‘Between Madame Bubble and Kitty Lorimer’, p. 99.

[37] Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/3/plan1824/T2, fol. 36r: ‘I [Marc Brunel] do estimate that the said work [the Tunnel] will be complete within three years unless prevented by some inevitable accident.’

[38] Lucy A. Newton, Philip L. Cottrell, Josephine Maltby, and Janette Rutherford, ‘Women and Wealth. The Nineteenth Century in Britain’, in Laurence et al., ed., Women and their Money, pp. 86-94 (p. 91). See also Froide, Silent Partners, pp. 151-77. For an example of women’s investments in more ‘risky’ ventures, see Helen Doe, ‘Waiting for Her Ship to Come In? The Female Investor in Nineteenth-Century Sailing Vessels’, Economic History Review 63.1 (2010), 85-106.

[39] Note, however, that their properties stood beyond the network of streets directly affected by the Tunnel works; the women did not have an opportunity to assent or dissent to the works, cf. Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/3/plan1824/T2 (map of affected streets); HC/CL/PB/6/plan1824/60, Estimate, Subscription List, Assents, fols 4r-26r and HC/CL/PB/6/plan1824/60, Book of Reference, fols 2r-9r (lists of assenting and dissenting property owners and occupiers).

[40] The Lady’s Magazine Or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex […], vol. 14 (London: G. Robinson, 1783), p. 335; Edward Josselyn Beck, Memorials to Serve for a History of the Parish of St. Mary, Rotherhithe in the County of Surrey and in the Administrative Country of London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907), p. 187; An Account of Public Charities in England and Wales (London: W. Simpkin & R. Marshall, 1828), p. 522.

[41] Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/3/Plan1824/T2, fols 32v and 33v-34r.

[42] Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/3/Plan1824/T2, fol. 34r.

[43] Parliamentary Archives, London, HL/PO/PB/3/Plan1824/T2, fol. 33r.

[44] 5 Geo. 4. c. clvi (Thames Tunnel Act 1824), para. I; Portman, The Thames Tunnel, p. 108.

[45] Freeman, Pearson, and Taylor, ‘Between Madame Bubble and Kitty Lorimer’, pp. 106-7.

[46] Thames Tunnel Company Act 1824 (5 Geo. 4 c. clvi), para. IV.

[47] Freeman, Pearson, and Taylor, ‘Between Madame Bubble and Kitty Lorimer’, p. 105; Portman, The Thames Tunnel, p. 63.

[48] Freeman, Pearson, and Taylor, ‘Between Madame Bubble and Kitty Lorimer’, p. 107.

[49] Thames Tunnel Company Act 1824 (5 Geo. 4 c. clvi), para. IV, provided that those who held twenty shares could cast five votes; while more shares could be purchased, no more votes could be cast.

[50] Wright, ‘Overseas Savings’, p. 662.

[51] Resolutions moved by His Grace the Duke of Wellington, and Passed at a Public Meeting of Friends to the Undertaking, held at Freemason’s Tavern, on Saturday, 5th July, 1828, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, Books 5581, fol. 2r.

[52] National Archives, London, HO 107/1490, p. 45.

[53] The Illustrated London News, 12 March 1887, vol. 90, p. 290.

[54] Beck, Memorials, p. 188.

[55] Will of Amelia Meilan, Archdeaconry Court of Probate, Middlesex, proved 21 April 1887.

[56] The Gentleman’s Magazine, Volume XIX. New Series (London: William Pickering, 1843), p. 547; Opregte Haarlemsche Courant, 1 April 1843, p. 2.

[57] The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, 23 September 1826, fol. 1v.