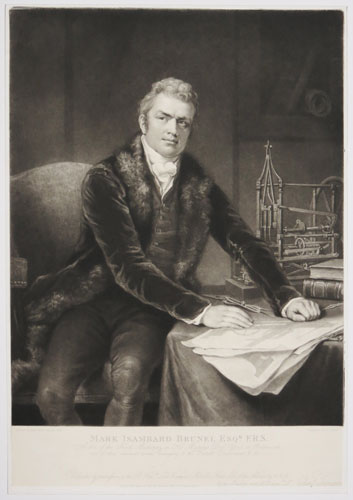

Who was Marc Isambard Brunel?

The Brunel Museum tells the stories of the first tunnel dug under a navigable river anywhere in the world.

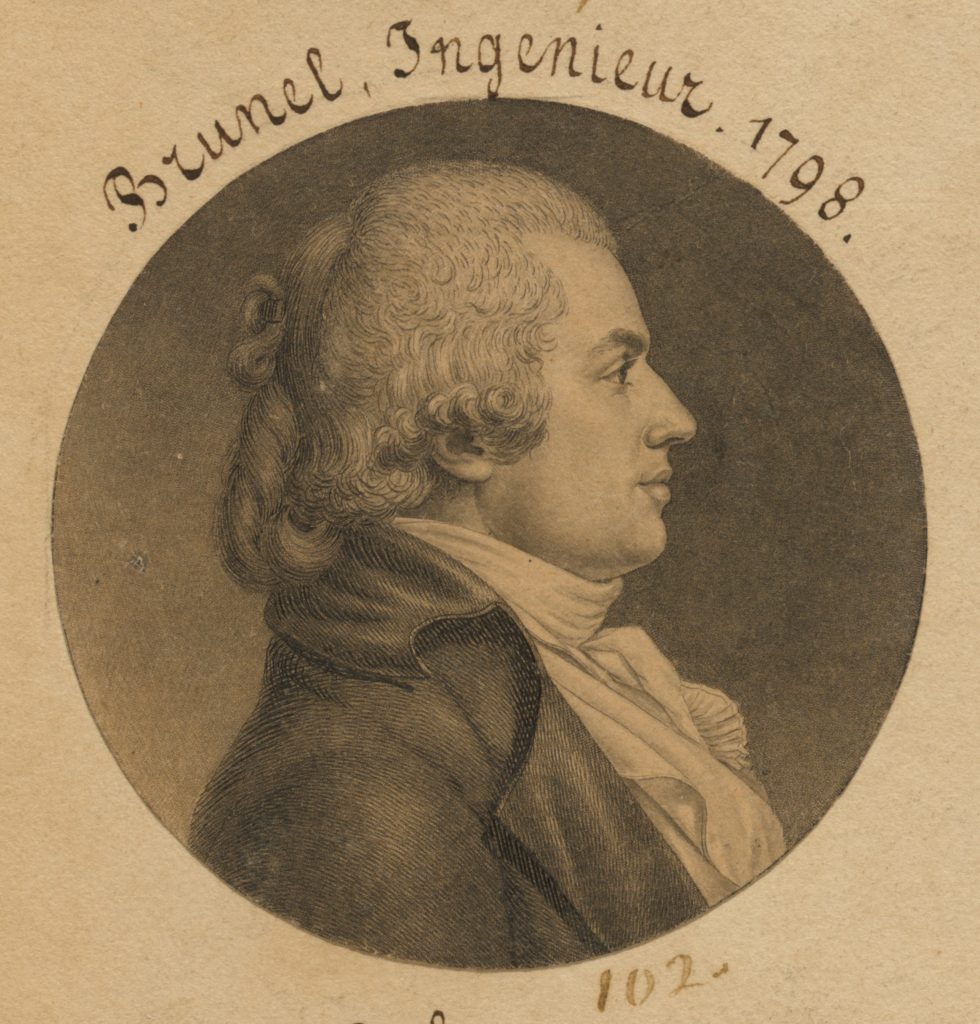

Designed by Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-49), the Thames Tunnel was a masterful feat of engineering, admired across the world, and became one of the most popular tourist sites in London during the 1800s, with many important visitors.

But who was Marc Brunel? Many recognise the surname Brunel due to the fame of Marc’s son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Fewer now know the name of his father, who was undoubtedly instrumental in encouraging his son to become an engineer, as well as a central figure in engineering history in his own right.

Brunel and the French Revolution

Marc Brunel was born in Hacqueville, a small village in Normandy, in 1769.

Rejecting a career in the clergy, he joined the French navy. Already, perhaps this aspect of his life explains a little of his lack of notoriety. Had he been born in Britain, he may have loomed larger in the national consciousness. After all, he worked at a time of fervent anti-French sentiment in Britain owing to the Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

Nevertheless, Brunel would gain vital technical experience while serving on board ships, travelling as far as Guadeloupe, until his eventual return to France in 1792. For someone like Brunel this could not have come at a more inopportune moment. A committed royalist, he returned to a country embroiled in a messy revolution where the king, Louis XVI, found himself becoming increasingly unpopular, with the monarchy officially replaced with a republic in September 1792.

If you were writing a fictional life of someone in the late 1700s for a book or film and wanted to make it exciting and feature key moments of the period, it is likely that it would end up looking something like Marc Brunel’s. After a run in with supporters of Maximilien Robespierre, one of the chief revolutionaries, in the lead up to the execution of the king in January 1793, Brunel fled to the United States: another country in the midst of some of the most important political developments in its history.

Brunel in North America

En route to North America holding a fake passport, Brunel met two fellow Frenchmen, Pierre Pharoux and Simon Desjardins, who were travelling to the US-Canadian border in order to map a tract of land, named ‘Castorland’, which had been purchased by a French company. They invited Brunel to join them, and he did, travelling for some months from September 1793 in upstate New York and around Lake Ontario. The trio visited areas of North America largely untouched by colonial expansion: Brunel reported seeing bears and indigenous Americans, and described himself and his companions as ‘new Christopher Columbuses’. Having found the mouth of the Noire River, Brunel then returned south, to New York.

First up was a plan for a canal linking the city’s famous Hudson River with Lake Champlain, further upstate. It’s almost as though Brunel grabbed the first body of water he saw and immediately set to work figuring out how to tame it for industrial us (though admittedly, Brunel actually joined a pre-existing project, and the original idea wasn’t his).

Most notably, Brunel submitted a design for what eventually became the US Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. – again underlining the momentousness of the period of American history in which he found himself. Despite winning the competition, his design was not actually used – another factor which may explain his relative obscurity. Also indicative of the general situation in the US in that period are designs produced by Brunel which working as Chief Engineer of New York City (a position he took on aged only 27). A cannon factory, and defences for Staten Island and Long Island, both indicate a nation not quite content that they had seen the last of their former colonial rulers.

Brunel's Early Projects in Britain

Brunel then decided to set sail for Britain, arriving in 1799, and shifted attention to helping the British Navy. His designs for making ships’ blocks, needed to hoist sails, mechanically would save the Navy masses of time and money, money which would be redirected into the pockets of the increasingly successful Brunel.

In 1810, Brunel also patented a machine for making boots. He hired army veterans to make them, and soon produced a large volume of footwear for the British Army. However, with the decisive end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 came financial ruin for Brunel: the Army no longer needed so many boots, and Brunel could not sell those he had made.

Brunel and Sophia Kingdom

Before discussing Brunel’s engineering exploits any further, let’s take some time to delve into the personal life of Marc Brunel during this period. Again, this could make for a convincing Hollywood romance.

As a young man, Brunel had met an Englishwoman named Sophia Kingdom (1775-1855), who was living in France and learning French. During the French revolutionary Terror of 1792-94, while Brunel fled, Sophia was imprisoned in France, and only made it back to England following the execution of Robespierre.

When Marc landed in Britain from North America in 1799, he immediately went in search of Sophia, whom he had last seen six years earlier. They married that same year. In a letter written in 1839, Marc reflected on Sophia Kingdom’s overwhelming importance in his life:

Without my dear Sophia […] I should never have surpassed the lowly limits of a Mechanic, and would probably have remained entirely stuck in America. Yet her constancy in the face of all difficulties gave me an opportunity to come to [the United Kingdom], to find a distinguished job which has made my fortune…

[Marc Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 1 September 1839, Évreux, Archives Départementales de l’Eure, côte 35/488]

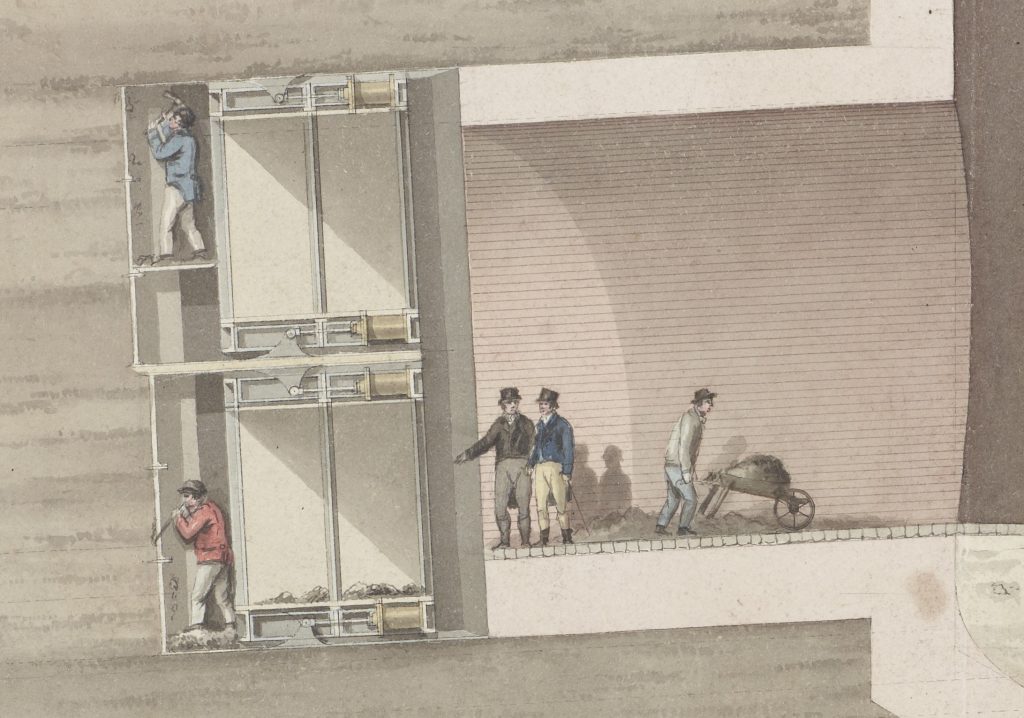

Brunel and the Thames Tunnel

After all these twists and turns in his life but now with a young family — two daughters, Sophia and Emma, and a son, Isambard — you might’ve thought Marc Brunel would decide to settle down and live a steady life in Britain. In fact, given the catastrophic collapse of his boot-making business, in 1821 he ended up in debtor’s prison with his whole family before he was bailed out by the government at the urging of the Duke of Wellington, among others.

Wellington would again push for government money to help Brunel finish his next, most famous project, the Thames Tunnel out of fears the French would stump up the money and claim ownership of what could be vital British infrastructure in any future war.

This tunnel — the first dug under a navigable river anywhere in the world — was inspired by Brunel’s observation in 1812 of a shipworm (teredo navalis) tunnelling into a piece of wood, as he later explained in a letter to his granddaughter:

I happened to see before me a piece of condemned Timber, a portion of the keel of a ship, wherein the sea worm, the Teredo navalis […], had made many erosions […] I then said to myself: ‘These little things have made little tunnels — so might we…’

[Marc Brunel to Sophia Hawes, 10 March 1842, National Maritime Museum, London, AGC 1.45]

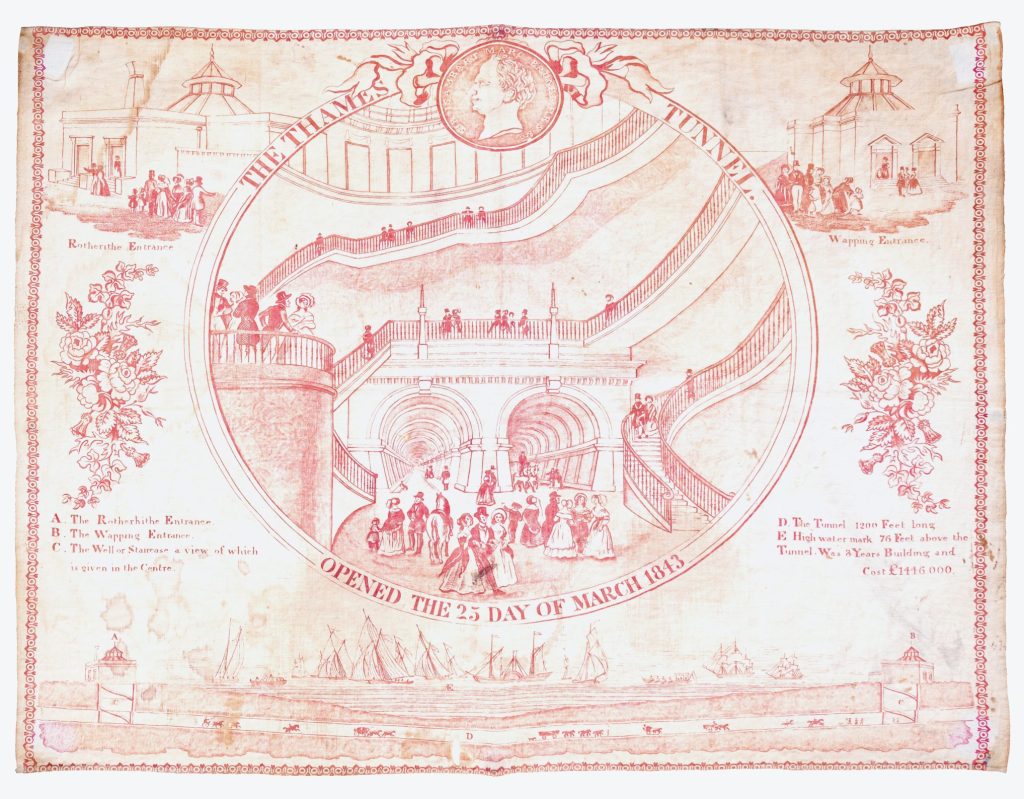

The Thames Tunnel would prove to be Marc Brunel’s most famous achievement but also his last. After a myriad of setbacks and delays, including four floods, the Tunnel opened on 25 March 1843. It operated as a pedestrian tunnel, becoming London’s greatest tourist attraction, until 1865. It was then sold to a railway consortium, converted for use by trains, and has seen rail traffic running through it constantly since 1869.

Marc Brunel died in 1849, six years after the tunnel opened, having long-suffered poor health, including a series of strokes. His growing frailty had become apparent even as early as 1831:

Experienced, this morning, just before breakfast, a very extraordinary sensation like something breaking in my chest rather on the left side. I was going to put my foot on the stairs, without any effort nor quickness. It almost knocked me down like an electric shock. It was instantaneous — the effect the whole of this day has been a sharp pain such as I have never experienced before…

[Marc Brunel, Diary, Wednesday 23 November 1831, Institute of Civil Engineers, London, TT/BD/7]

His legacy, however, lived on: partly through the exploits of his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and his grandson, Henry Marc Brunel, both of whom became engineers; and partly through the Thames Tunnel itself, now one of the oldest parts of London’s public transport infrastructure.

This has been a brief overview of the extraordinary life of Marc Brunel, but for the even more extraordinary story of the Tunnel, you’ll have to come visit the Brunel Museum in Rotherhithe!

This biography was developed from a blog written by Peter Angove during an internship at the Brunel Museum in Autumn 2023. The internship and blog formed part of his assessment in History at Queen Mary University of London, and were part of studies into public history and the work of the heritage sector. The page has since been adapted with his permission and collaboration for publication on this website