The Brunel name is inextricably linked with the great nineteenth century steamships. However, long before Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed and launched three world-changing ships, his father, Marc Brunel, had been involved with steamships: and not in Britain, but in the United States. In our latest blog, Mark Kleinman considers Brunel’s engagement with American steamboat pioneers in the 1790s to help better understand his wider story and achievements, and emphasise the importance of the crucial years Brunel spent in the United States.

The Brunel name is inextricably linked with the great nineteenth century steamships and the dawn of steam-powered inter-continental travel. Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed and launched three world-changing steamships, and earlier in 1813, Isambard’s father, Marc Brunel had designed The Regent which operated successfully as a mail-boat on the Thames between London and Margate.[1]

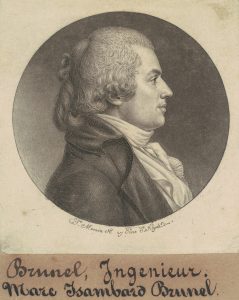

Charles B.J. Févret de St. Mémin, portrait of Marc Brunel, 1798. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2015.19.1584.8.3

But Marc Brunel had been involved with steamboats much earlier than this. And not in England, but in the United States of America, where he lived from 1793 to 1799. This is a dramatic tale of big ambitions and even bigger rivalries, of invention and obsession, of patents, monopolies and legal battles, of fallings-out within families. You can read about it in more detail here.

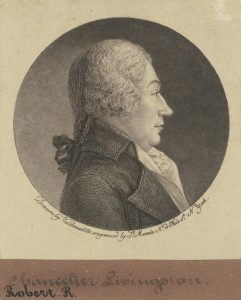

Some time in 1797 or 1798, one of the early American steamboat pioneers, Colonel John Stevens, working with Nicholas Roosevelt, a distant relative of the two later American Presidents, and backed by the powerful Robert R. (‘Chancellor’) Livingston, one of America’s ‘Founding Fathers’ approached Marc Brunel for help. Marc Brunel had become an American citizen in 1796, and was living in New York in 1797 and 1798.

Anon., portrait of Col. John Stevens, about 1830. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C., NP3.75.13

Charles B.J. Févret de St. Mémin, portrait of Robert R. Livingston, 1796. National Gallery, Washington, D.C., 2015.19.1584.1.3

Stevens’ approach to Brunel suggested that Brunel had already developed some reputation in America as an engineer – a profession in very short supply on that side of the Atlantic. In addition, he had considerable experience of the practicalities of navigation on both ocean-going ships and smaller boats on American rivers. He’d been a sailor in the French Navy in the Caribbean for six years, and later directly experienced the difficulties of navigating American rivers – just about the only way to the interior – in his work in the Hudson Valley for the Castorland company.

Frustratingly, we do not know exactly when he met John Stevens, who was looking for ‘something new in engines.’[2] That ‘something new’ was internal combustion, a possible way of making a steamboat engine lighter and more efficient. This idea – to apply an internal combustion engine to the problem of the steamboat – was not as outlandish as might appear at first sight. Internal combustion had been known about for at least a century, and Robert Street, and Englishman had ignited gases to drive a piston in 1794.

And so in 1797-78 Marc Brunel was trying to build a working model based on Stevens’ ideas. Brunel wrote to Stevens on 30 January 1798 setting out his commission from Stevens, and, presumably at Stevens’ insistence, made clear that the idea originated with Stevens and not with Brunel.[3]

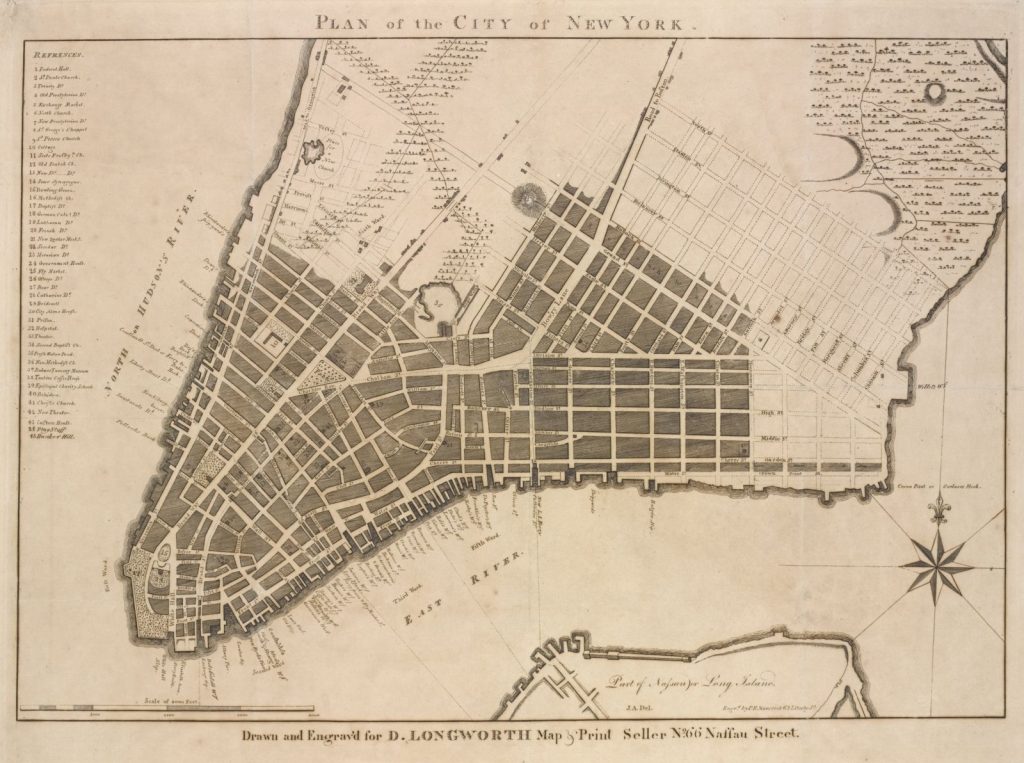

We can picture Marc Brunel, a man in his late 20s, full of ideas and energy, in the winter of 1797/98, in a dingy downtown workshop in the primitive industrial milieu of post-Revolutionary New York City. He is experimenting to create a working model of an internal combustion engine, a machine powerful enough to pull a laden boat along a river. It sounds like a science fiction or alternative history fantasy – but nevertheless it happened. Marc Brunel was finding his metier.

We know nothing about Brunel’s New York manufactories beyond their addresses. It is clear from his letters to Stevens that he employed men to work in his manufactory, and he received both payments and loans from Colonel Stevens – but how many men worked for Brunel, who were they and what skills did they possess? What other inventions was he working on at this time, and how was he making his living?

We do know that Chancellor Livingston wrote to William Constable on 4 November 1798, asking him to meet James Watt in London in order to purchase a steam engine. Three months later, Marc Brunel had himself left for England, never to return to the USA. Was Brunel’s journey partly related to Livingston’s desire for a Boulton and Watt steam engine?

Moreover, Brunel wrote to Livingston on 14 January 1799, just before his departure to England as follows:

Expecting to sail for London by the 25th, at latest, of this month, I offer you the services it might be in my power to render you on the subject of your late improvements on hydroliques [sic] and steam machine..I am able to bring your invention to an early practice by making a model of about 150th power upon which I will be able to make all the experiments requisite to ascertain the practicability of this valuable discovery.[4]

Brunel goes on to pitch to Chancellor Livingston both for an advance and for a share in profits. It is a remarkable letter. On the eve of his departure for England, and with Constable presumably already in London and negotiating with James Watt, Brunel is delicately but clearly suggesting to Livingston an alternative course of action via Livingston authorising Brunel to make a model of a Livingston-designed steam engine. We know that Livingston was strictly an amateur inventor, with limited technical knowledge or practical skills – his important contribution was as a funder of projects and an important politician. It is likely in my view that Brunel was flattering the Chancellor into releasing the money and agreeing to a profit-share before perhaps planning to design his own engine.

We have no further record of Brunel working with Stevens, nor of any further development of the internal combustion idea as the method of propulsion for a steamboat. Much later, in England, Marc Brunel with his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel for about ten years unsuccessfully pursued the idea of a ‘gaz engine.’ This was not an internal combustion engine, but rather an engine that made use of the then-recent discoveries by Humphrey Davy and Michael Faraday that a number of gases could be liquefied by the use of low temperature and very high pressure.

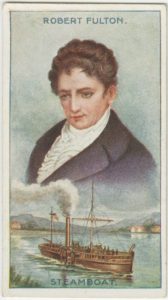

Robert Fulton and his steamboat, commemorative cigarette card, 1850. New York Public Library, H46-12-2

Fulton and Livingston are generally credited with inventing the first successful steamboat. But a case can be made for at least equal billing for Stevens and Roosevelt earlier. Their achievements do not as far as we know relate directly to Brunel’s internal combustion experiments. But as a skilled engineer and former mariner, perhaps Brunel made other suggestions to them? Until and unless we find further letters or other evidence from this time, this must remain speculation.

Nevertheless, Brunel’s engagement with some of the American steamboat pioneers in the 1790s helps us to understand better his wider story and his achievements, and also brings out the importance of the crucial years he spent in the United States.

First, to what degree was Brunel involved in Livingston’s plans to buy a steam-engine from Boulton and Watt in England? Was this the reason – or at least one of the reasons – why he decided to come to England in early 1799?

Secondly, by the late 1790s, it is clear that he had built and important reputation in the USA. This reputation was sufficient for Stevens directly and for Roosevelt and Livingston indirectly to seek Brunel’s help when their steamboat project ran into difficulties.

Thirdly, Marc Brunel’s location, not just in America, but specifically in New York City was important. He was living and working in New York just at the point when the somewhat ramshackle former Dutch trading post was beginning its rapid trajectory from global backwater to world city.

Fourthly, by working for Stevens, Roosevelt and Livingston, he was connected, at least indirectly, and possibly directly, with the global centre of innovation and industry – England in general, and Boulton and Watt’s Soho works in Birmingham in particular.

Finally, this episode shows that by the end of his time in the USA, Brunel was clearly brimming with ideas and inventions and enjoying the role of inventor. This justifies his own comment, ascribed to him by his descendant Celia Brunel Noble that he brought with him from America to England ‘some small means and many great ideas.’

I wish to thank Crystal Toscano (Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, the New York Historical Society) for scans of letters from Marc Brunel to Robert R. Livingston in 1801 and 1802 in the Robert R. Livingston papers 1707-1862; and Leah Loscutoff (Samuel C. Williams Library, Stevens Institute of Technology) for digitised letters from Marc Brunel to Colonel John Stevens, and also for a copy of R. L. Dubois’ PhD thesis. Thanks also to Jack Hayes (Brunel Museum) for comments.

References

[1] Paul Clements, Marc Isambard Brunel (London: Longmans, 1970), pp. 62-63; Steven Brindle, Brunel: The Man Who Built the World (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005), p. 33.

[2] Turnbull A., John Stevens: An American Record (New York, NY: The Century Co., 1928), p. 139.

[3] Marc Brunel to John Stevens, 30 January 1798, Stevens Institute of Technology, Samuel C. Williams Library, Stevens Family Papers, Reel 12, ref. 651; also in Turnbull, John Stevens, pp. 139-140

[4] ‘Lot #209 Marc Isambard Brunel Autograph Letter Signed’, RR Auctions 2021, cf. https://www.rrauction.com/auctions/lot-detail/345137406220209-marc-isambard-brunel-autograph-letter-signed/