Monday 10 November 2025 is the 198th anniversary of an extraordinary dinner, held under the waters of the River Thames in the Thames Tunnel. In our latest blog, Museum volunteer Sue Thomas reveals a raft of new information about the dinner, following her exciting discovery of a file of RSVPs sent to the Brunels.

Monday 10 November 2025 is the 198th anniversary of an extraordinary dinner, held under the waters of the River Thames in the Thames Tunnel.

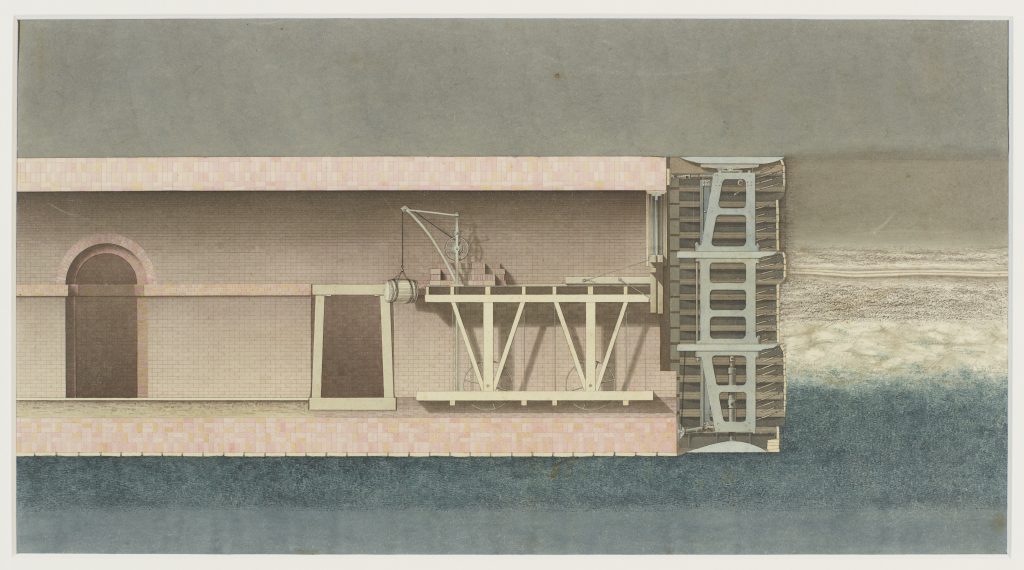

Cross-section of the part-finished Thames Tunnel and tunnelling shield. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.8.

Marc Brunel’s project to build the first tunnel under a navigable river anywhere in the world had begun in March 1825 with the sinking of the Tunnel Shaft at Rotherhithe, part of the Brunel Museum today.

Progress under the river, using Marc Brunel’s patented tunnelling shield, had started in November 1825. In May 1827 the river broke in for the first time. Luckily, no one was killed. Marc and his 21-year old son Isambard, by that time resident engineer on the project, were able to find the part of the Tunnel’s roof that had been damaged by dredgers, seal the hole and pump out the Tunnel. Work started again on 30 August.

On 10 November, a dinner was held to celebrate completing 20 feet (6 metres) of the tunnel after work had restarted. Those 20 feet of tunnel had taken over two months to dig, so difficult were the conditions as the Tunnel reached the middle of the river. Following the well-publicised flooding, a public relations coup was needed to bolster faith in the project which was in financial difficulty. An extravagant banquet offered precisely that.

Newly-Uncovered RSVPs to the Thames Tunnel Banquet of 1827

I recently made an exciting discovery at The National Archives in London, a file of letters — RSVPs for the dinner sent to the Brunels — which were stashed amongst a mixture of railway archive material.[1] These letters help flesh out preparations for the dinner: clearly sent out at short notice, they imply the dinner was hastily conceived. The content of the replies suggests many invitees chose to send their sons in their place, considering the unusual location more suitable for a young man’s celebration.

The response of Robert Humphrey Marten, a Director of the Thames Tunnel Company, is indicative of this attitude. Marten wrote that his son would be attending and cautioned Isambard that:

Babylon was captured because of Carelessness during a feast: – and your Enemy the Thames has at first a silent, wily, manner of approach ‘till he has gained his point, and then he is an irresistible thunderer. — Beware therefore of slips ! and mind to break up early, so as not to endanger either your health, or your sobriety.[2]

Also in the file is a previously unpublished letter from the scientist Michael Faraday.[3] Written a few days after the event, Faraday stated he was ‘upset’ to have missed the dinner, as he was away in Ramsgate when his invitation had arrived. Still, he wrote that he was ‘proud to be called “one of you”, “a tunnel man”.’[4]

Invitees were carefully chosen. They included Edward Baldwin editor and owner of The Standard newspaper: this new paper had started publishing in May of that year, with a front-page article about the flooding of the Tunnel based on a report received directly from Marc Brunel.[5] Perhaps unsurprisingly, a full report on the banquet duly appeared in The Standard on Monday 12 November.[6] The article notes that ‘In the western arch was held a dinner for 30-40 gentlemen while in the eastern arch a group of 100 miners and bricklayers sat down to a less splendid occasion’. Though much of the article concentrates on the toasts given after the meal, I have been thus far been able to piece together a list of eighteen men we know were present.[7]

Painting the Banquet of 1827

Other invitees included the painter, amateur engineer, and friend of the Brunels, John Martin. He too was unable to make it, having to drop out at the last minute due to the arrival of a friend; he apologised and noted that he was ‘extremely glad to hear you are proceeding so rapidly with the Tunnel & shall be happy to congratulate you on the completion of your arduous undertaking’.[8]

Martin’s invitation is intriguing, since the dinner was recorded by artists. While Martin didn’t attend, The Standard article notes that one ‘Mr Ramsay’ (almost certainly Scottish portraitist James Ramsay) ‘early left the table, in order to make a coloured sketch of a scene which, from its remarkable contrast of light and shade, would have been worthy of Rembrandt.’ Ramsay’s sketch was exhibited at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition the following year.[9] It was then displayed again at a conversazione at the Institution of Civil Engineers on 6 June 1871, lent by Sophia Brunel, sister of Isambard.[10] It is unknown whether Ramsay was invited specifically to document the occasion; so too is the current location of the sketch.

One of the best records of the dinner is an oil painting, now in the collection of Ironbridge Gorge Museum. This painting of the 1827 Tunnel banquet is attributed to George Jones, a Royal Academician who had previous produced work including a painting of the coronation banquet of George IV (1821-22) which bears some resemblance to the Tunnel banquet painting. Still, little is known about Jones’ knowledge of the Tunnel banquet, whether he was present or even invited, and the possible relationship of his painting to Ramsay’s sketch.

Jones’ painting employs much artistic licence. As we will see below, the scale is hugely exaggerated. We are left to wonder about the possible influence of John Martin’s dramatic style, such as found in his hugely popular Belshazzar’s Feast, which had toured the country between 1821-26, on Jones’ painting. Figures are conspicuous in their presence or absence: Marc Brunel and Isambard Kingdom Brunel can be seen in conversation in the foreground, despite the fact that on the day of the dinner Marc was ill and unable to attend. The Duke of Wellington appears to be sat the near end of the table; while he was a friend of Marc Brunel’s and an important supporter of the project, his presence would surely have been noted in the newspaper article. Finally, the 100 workers — seated at their own long table in the other arch — are all omitted from the scene.

In essence, Jones’ painting provides less documentary evidence of the banquet than it does evidence for the banquet’s glorification after the fact, as part of the Thames Tunnel Company’s wider drive to instil public confidence in the project. Even so, and unusually for the period, no engravings of the painting are known. There are however at least one, and possibly two, copies or versions of the same painting which remain in private collections.

Not Just 1827: New Evidence for Other Banquets in the Thames Tunnel

The 1827 banquet in the Tunnel is often thought of as the banquet in the Tunnel. In fact, it was not the only such banquet in the Tunnel while it was under construction.

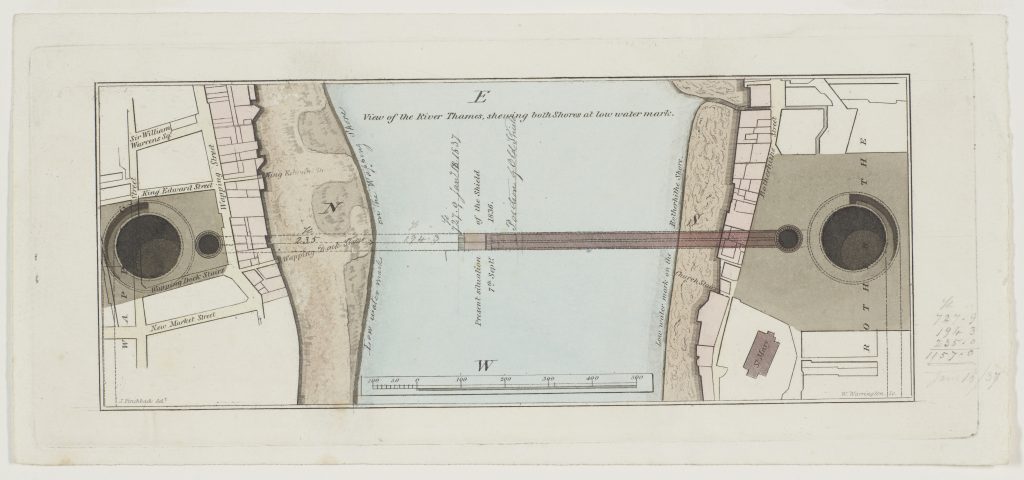

Map showing progress of the Thames Tunnel. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.27

In late summer 1839, reports of a huge dinner to celebrate the Tunnel reaching the low water mark at Wapping appeared in the press. It was stated that:

The Directors of the Thames Tunnel company gave an elegant dinner in the Tunnel, to the persons employed in that undertaking, to celebrate having reached low-water mark […] 280 persons sat down to table. On a raised platform, about 500 visitors, the majority of whom were ladies, were provided with places to view the scene.[11]

This dinner was reported on as far afield as New York, where it was claimed that dining to celebrate achievements was a particularly English trait, but that ‘On some very protracted occasions, it appears, they cannot restrain their impatience for the feast until the work in hand is completed.’[12]

For a sense of scale, the table to accommodate 280 diners would probably have been around 85 metres long when the total length of the Tunnel at that time was 290 metres. As there was still only access to the Tunnel from the Rotherhithe end, those seated at the far end of the table would have had a very long way to run if anything had gone wrong!

The reports of the 1839 banquet are notable as they provide very clear evidence of women at a dinner in the Tunnel — albeit as spectators, rather than diners. With the exception of an event which welcomed the wives of the miners to the Tunnel in April 1827, these large-scale events seem often to have been single-sex affairs.[13]

There is no clear mention of a dinner for the workforce this time; perhaps the other bore of the tunnel, with its many cross-passages, was utilised to provide access for so many people at once. However, a letter by Marc Brunel leads us to ask whether the workers did indeed participate in this dinner, or another around the same time. Writing of the mens’ illness caused by poor airflow, Brunel noted that: ‘Our men’s energy and perseverance are truly admirable. They get stuck in — we are to give them a great dinner next Friday in our works.’[14]

The search is now on for more sources. Who dined in the Tunnel in 1839? Were the workers invited? And were there yet more dinners held in the Tunnel in other years?

1827 to 1997: A Modern Tribute to the 1827 Banquet

We do know of another dinner that happened some 170 years later. In the 1990s, major concern over the safety and security of theThames Tunnel, which had been in use by trains since 1869, led to a project to reline the Tunnel.[15] Though complicated by the granting of a Grade II* listing for the Tunnel just 3 days before the refurbishment was due to begin, the work ultimately succeeded in protecting a piece of internationally important heritage whilst ensuring its continued use as a key part of London’s transport infrastructure.

The banquet in the Tunnel, 1997. Photo courtesy of John Bostock.

To celebrate Marc Brunel’s achievements, as well as the successful completion of the refurbishment project, another dinner was staged inside the Tunnel in March 1997. While most of the Tunnel was relined in concrete, a number of arches at the Rotherhithe end were left in their original state. These were the venue chosen for this modern banquet.

It is fascinating to compare the original painting with the photo of the 1997 dinner, particularly with regard to the scale!

Since reopening after the refurbishment works in 1997 the tunnel has been in daily use carrying passengers between Rotherhithe and Wapping on the Overground, now known as the Windrush Line.

With thanks to John Bostock for permission to reproduce his image of the 1997 banquet.

References

[1] The National Archives [TNA], London, RAIL 1008/79, catalogued as ‘Thames Tunnel – celebrations on completion of a further 20 ft after the inundation etc.’

[2] Robert Humphrey Marten to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, undated [but 9 November 1827], fols. 1r-1v, in TNA, RAIL 1008/79.

[3] Faraday’s extant letters were published as The Correspondence of Michael Faraday, ed. by Frank A. J. L. James, 6 vols (London: Institution of Engineering and Technology, 1991-2011); this letter is not among them.

[4] Michael Faraday to Marc Isambard Brunel, 15 November 1827, fol. 1r, in TNA, RAIL 1008/79.

[5] Dennis Griffiths, Plant Here the Standard (London: Macmillan, 1996), p. 43. For Baldwin’s RSVP, see Edward Baldwin to unknown [Isambard Kingdom Brunel?], undated, early November 1827, fol. 1r, in TNA, RAIL 1008/79.

[6] ‘Dinner at the Thames Tunnel,’ The Standard, 12 November 1827.

[7] So far, I have identified across sources: James Bandinel, honorary secretary of the Thames Tunnel Company; Benjamin Hawes Junior, Director of the TTC; George Humphrey Marten, son of the TTC Director Robert Humphrey Marten; Richard Beamish and William Gravatt, engineers working on the Tunnel; Henry Maudslay, who was responsible for building the tunnelling shield; William Codrington, son of the TTC shareholder, Admiral Sir Edward Codrington; James Ramsay, the Scottish portraitist; the medic, Algernon Frampton; and one Captain Stevens, equerry to the Duke of Gloucester.

[8] John Martin to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, 13 November 1827, fol. 1r, in TNA, RAIL 1008/79.

[9] The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, MDCCCXXVIII. The Sixtieth (London: W. Clowes, 1828), p. 19: “‘Sketch of a dinner given in the Thames Tunnel on the 10th of November 1827’, J. Ramsay”

[10] Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers; with Abstracts of the Discussions. Vol. XXXII. Session 1870-71, Part II, ed. by James Forrest (London: Institution of Civil Engineers, 1871), p. 434: ‘”A Banquet in the Thames Tunnel During the Progress of the Works,” J. Ramsay. [Lent by] Lady Hawes.’

[11] The Annual Register; or A View of the History and Politics of the Year 1839 (London: ‘Printed for J.G.F. and J. Rivington, 1840), p. 162.

[12] ‘Letters from London,’ The New York Mirror, 2 November 1839.

[13] Marc Brunel, Diary, Institution of Civil Engineers, London, TT/BD/2 (Sat. 14 April 1827): ‘The wives of the miners were admitted one thousand persons at once were in the west arch.’

[14] Marc Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 1 Sept. 1839, Archives Départementales de l’Eure, Évreux, côte 3F/488 (‘L’Energie et la perseverance [sic] de nos gens sont vraiment admirables — Ils s’attachent à la chose — nous devons leur donner un grand diner [sic] vendredy [sic] prochain dans nos régions.’)

[15] See M. J. Roach, ‘The Strengthening of Brunel’s Thames Tunnel,’ Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Transport 129.2 (1998), 106-15.