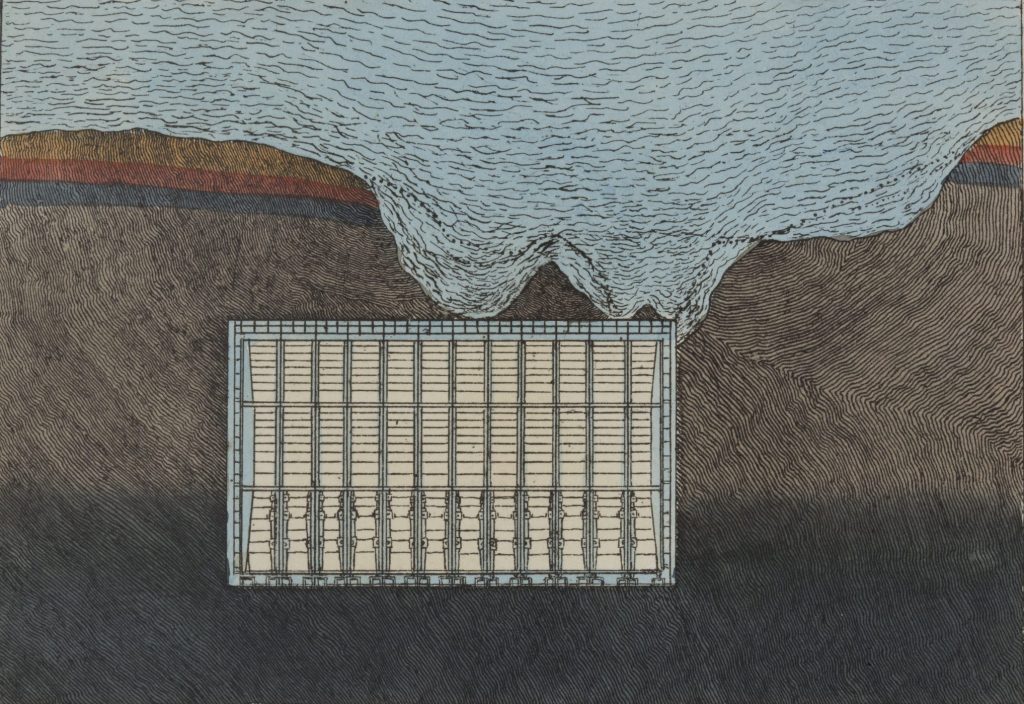

This watercolour wash view shows a cross section of the tunnel with the intrusion that caused the first flood on the 18th of May 1827. Unlike some of the other pieces in this collection showing the first flood (see LDBRU:2017.16 and LDBRU:2017.17), this piece is small in scale, at only 128mm x 90mm, and therefore lacks the same level of detail and finishing.

The tunnel shield is shown at a cross section with each of its cells, while its wider view gives context to the riverbed’s normal level and the scale of the intrusion.

The first major flood was a pivotal moment in the tunnel’s story. At 548 ft. in length, the tunnel had met a cavity believed to have been caused by dredging and worsened by the anchors of a series of collier boats the previous day. In the weeks preceding the flood, stones, coal, bones, glass and china had been entering the tunnel, but it was on 18 May that the cavity filled with tidal dirt and debris gave way and rushed into the tunnel. There would be another 4 major floods during the tunnel’s construction, the second of which led to nearly a 5 year hiatus in its construction from August 1828 to March 1835.

During the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, in the early 19th century, engineers began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for bringing engineering to the masses and shaping public perception. Those intended for the workplace included specifics and details crucial for engineers, but presentation drawings like this one were designed for the public eye. They lacked any technical detail and aimed to be visually pleasing, easily comprehensible, and easily reproduced.

In fact, this piece, aside from the watercolours, is identical to what was mass-printed in booklets titled “Sketches of the Works for the Tunnel Under the Thames” sold at the tunnel and across London. Brunel and his team were almost certainly keen to mitigate negative public perception of the disaster, and presentation drawings widely distributed in these booklets were the perfect means for doing so. No damage is shown at all to either the shield or the tunnel’s structure and, with the accompanying text, help portray the flood as a minor setback overcome by capable engineers.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and the draughtsmen who created many of them soon solidified their role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, his chief mechanical draughtsman, Joseph Pinchback, was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.