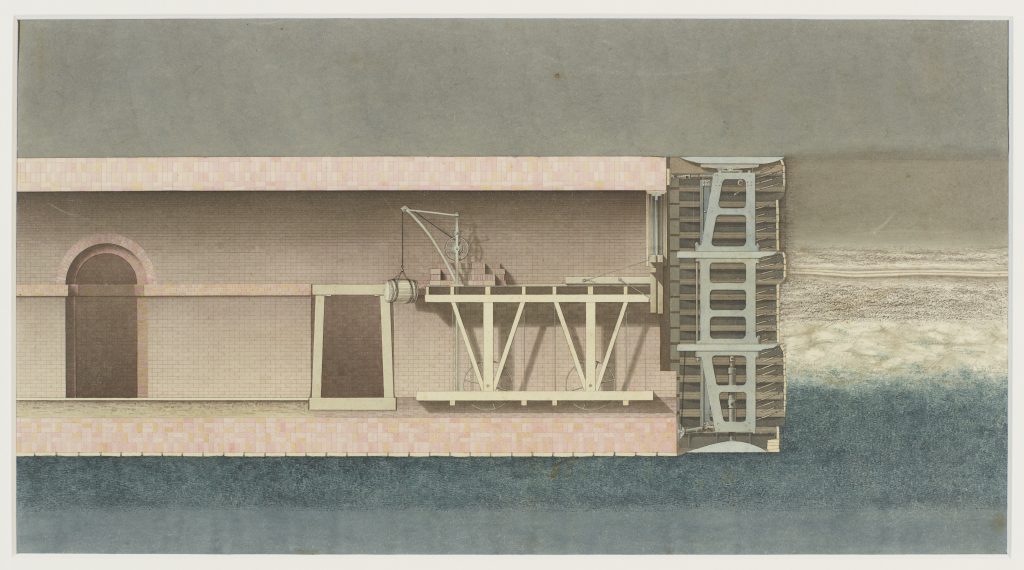

This watercolour piece dates from the early 1820s and depicts a chronology of the tunnelling process. On the far right-hand side, the different strata of earth are distinguished with different patterns and colours. On the left is the tunnelling shield, its movable stage, which supplied bricks and other building materials to the front, and two archways shown in various stages of completion. While no markings indicate authorship, other pieces of a similar style were done by Joseph Pinchback, Brunel’s chief mechanical draughtsman.

From afar, a cross-sectional drawing like this creates powerful imagery of progress and the tunnel displays a striking resemblance to the teredo navalis shipworm that Brunel noted as a source of inspiration. The predictable and parallel strata of earth in many of the illustrations from the early 1820s show a level of confidence in the project that would not be shifted until tunnelling was well under way. Richard Beamish, in his 1862 memoir of Marc Brunel, writes: “Here then was a totally different character of ground from that which had been represented in the report of the surveyor, and announced by the directors on the 20th of July, 1824, and in place of ‘a stratum of strong blue clay of sufficient depth to ensure the safety of the intended tunnel’, a variety of strata was found varying in density one from another, and in themselves under different circumstances; and it must be obvious that a machine, which was designed to operate in homogenous blue clay, was scarcely calculated to content against a friable sand, or sand so impregnated with water as to have become absolutely fluid.”

Upon closer inspection, plenty of small details reveal how work was carried out. On the left side of the shield are the large propelling screws, which were used to drive the shield forwards. To the right, up against the earth, are the poling boards and poling screws, which were removed one by one for excavation. A pile of bricks can also be seen on the platform, ready to line and support the new length.

Interestingly, it is completely devoid of any figures — which hints at the intention behind this watercolour and even others held by the Museum. Here, we have a detailed and meticulously drawn illustration of the Tunnel’s design that emphasises its engineering marvel. This type of illustration is believed to have been used as a ‘presentation piece’ to exhibit designs to high-profile individuals, potential investors, and even government officials. Drawings like this often had several lives. For example, we know from the diaries of one of Brunel’s employees, Gilbert Blount, that it was not unusual for several hands to have been involved in a single drawing and for it to have multiple iterations. In this case, an engraved version would appear in guidebooks dating from at least 1827. Mass produced for the general public, the only key difference would be the included workers, presumably to add a human element.

Technical drawings had become an integral part of engineering throughout the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900). However, in the early 19th century, engineers including Brunel began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for shaping public perception and engaging public interest.

Their purpose can be gleaned from certain characteristics in their visual appearance. For example, those intended for the workplace were more likely to incorporate technical details, but pieces like this one favoured a pictorialist use of colours and lighting. These traits created an appealing visual style, and were easily transferred to engraving and mass-dissemination via print.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and draughtsmen like Pinchback soon solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. Brunel had various employees — both draughtsmen in official capacity and other positions — produce and modify the watercolours in this collection, and their impact to the eventual success of the tunnel should not be understated. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.