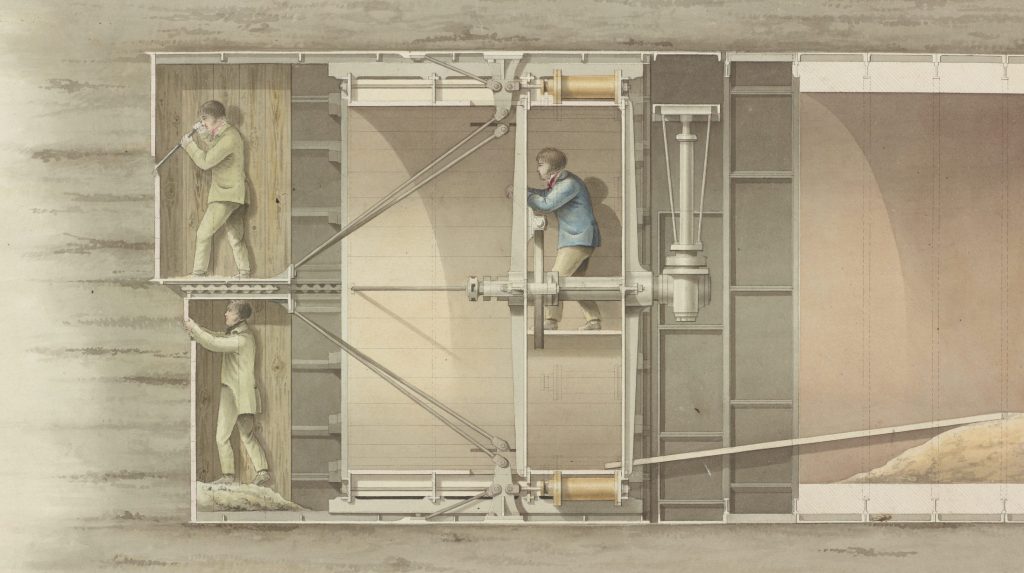

An early watercolour technical illustration of the tunnelling process. This piece was likely drawn by Joseph Pinchback, Brunel’s chief mechanical draughtsman, and is cut from a sheet dated September 1818. See LDBRU:2017.5 and LDBRU:2017.20 for the complete page and other views of the design.

Two miners are featured excavating earth inside individual compartments. Close inspection shows the way in which individual miners would work: rows of ‘polling boards’ held back the earth and would be removed and replaced individually for digging. Behind them, a third worker appears to be overseeing advancement of the shield. A waste tip heap can be seen further to the right, as well as a new length of the tunnel ready to be strengthened with casing (cast iron or brick).

In Brunel’s patent no. 4204 for “Forming tunnels or drifts underground”, published a few months prior on 20 January 1818, he described two tunnelling methods. One used a shield made up of several cells driven forward by hydraulic rams. The other, which this design more closely resembles, was inspired by the shipworm and used a centrally-located auger and a circular shield design.

Compared to the final design used for construction in 1825, this early iteration has a few notable differences. Most obvious is the shield depicted with two levels, rather than the three that were eventually used. Secondly, the shadowing on the tunnel wall suggests a circular tunnel design (this is more easily identified in LDBRU:2017.19 and LDBRU:2017.20). Lastly, the hydraulics system shown here was replaced by a simpler screw system.

Throughout the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, in the early 19th century, engineers began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for shaping public perception and bringing engineering to the masses.

Those intended for the workplace included technical details needed to bring the design to reality. However, pieces like this one differed in that they were created for a more public audience. As presentation pieces, they appealed to the layman through the use of watercolours and directional lighting, which helped the untrained eye visualise the design, and by omitting any unnecessary and complicating details. These traits, alongside their reproducibility, created a characteristic style that helped bring the industrial world into the public domain.

Brunel was one engineer who used technical illustrations as a promotional tool to grow an audience and publicise designs. For example, this piece dates back to 1818 when Brunel was still planning and campaigning for the tunnel, and it would be another seven years until construction of the tunnel began. These visually appealing watercolours would have played a role in the process of sharing designs and gaining support from several significant investors, as did various illustrations reproduced for pamphlets and publications such as the Mechanics Magazine.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and draughtsmen soon solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.