To mark Chinese New Year our volunteer Keith Turpin reflects on the connections to China around the Brunel Museum:

Local landmarks

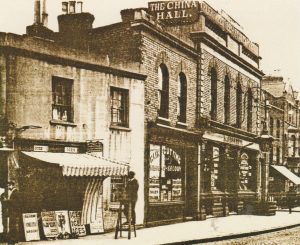

There are lots of clues to Southwark’s Chinese connections. Near the museum you will find Cathay (an archaic term for China) Street. The China Hall on Lower Road, another local Rotherhithe landmark, was a pub and theatre venue, so named after being leased to tea trader & entrepreneur Jonathan Oldfield in 1776.

China Hall 1916 http://russiadock.blogspot.com/2015/01/the-china-hall-rotherhithe.html

Nearby Bermondsey was known as the Larder of London, and Rotherhithe as Sailor Town, an early melting pot of ships’ crew members, chandlers and dockers from all over the world. The term lascar, from the Portuguese, originally embraced any sailors or militia from east of the Cape of Good Hope. Sailors of many ethnicities including the Japanese, Chinese, Indian and Malays, would have been familiar sights in the great shipyards of Blackwall, Deptford and Millwall where Brunel’s iron steamship the Great Eastern was constructed from 1854. There may have been Chinese workers who directly contributed to Brunel’s great ship. The Eastern Steam Navigation Company sought to establish a shipping line to east Asia, including China. Although the SS Great Eastern never went to China, the other great iconic ship on our stretch of the Thames, the tea clipper Cutty Sark, made 8 voyages to China to service Britain’s unquenchable thirst for our national brew.

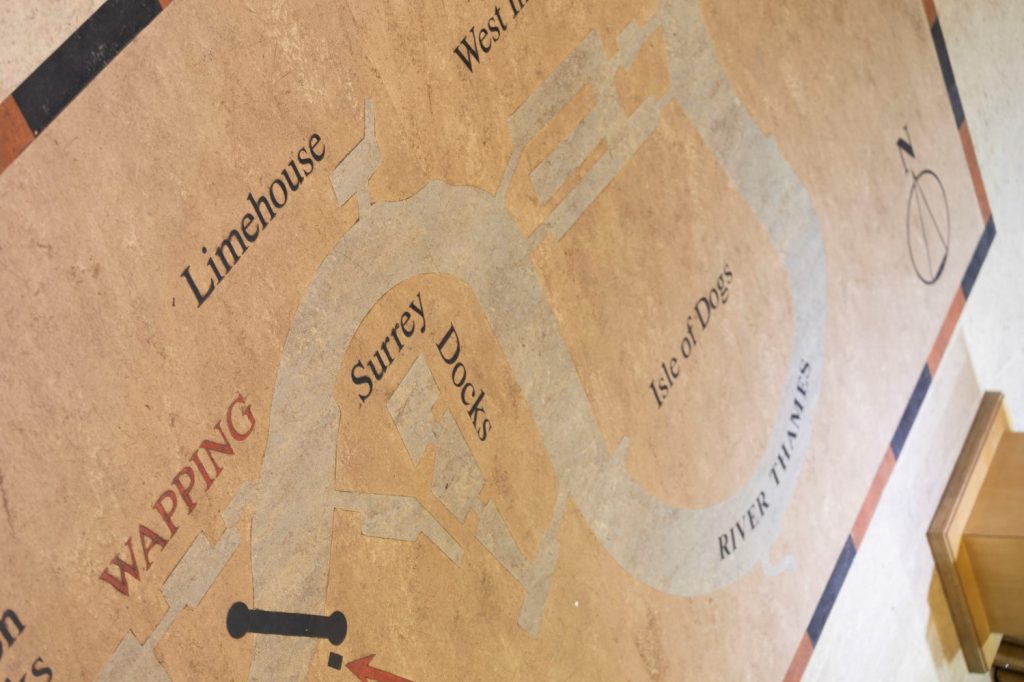

The original Chinatown

Across the river in Limehouse, Pekin, Nankin and Canton Streets are all reminders of the local Chinese heritage going back to at least the 18th century, when demand for Chinese commodities such as tea, silk and porcelain was enormous, bringing both merchandise and seamen into the great port of London.

Home to the Chinese community, Limehouse was known as China Town until the Blitz displaced them to Soho in central London. The Chinese community in Limehouse suffered from crudely stereotyping depictions of opium dens, steaming laundries and moral degeneracy. This was the type of exoticising and scapegoating that befell many minorities in literary representations, from Dickens’ the Mystery of Edwin Drood to Sax Rohmer’s character Dr. Fu Manchu. The reality was closer to a poor, hardworking community served by shops, businesses, and a Confucian temple catering for their needs, amongst many other minorities living cheek by jowl in the great but harshly deprived Victorian metropolis.

circa 1935: London’s Chinese quarter, Chinatown, in the 1930’s. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)