In David Copperfield (1849-50), Charles Dickins wrote about a speculator’s scrap yard in a rundown area of London now known as Pimlico. Sited on marshy ground alongside Millbank Prison on the bank of the river Thames, half buried in the mud were “rusty iron monsters of steam-boilers … anchors … diving-bells … and I know not what strange objects”. The Industrial Revolution (~1760-1830/40) had been driven by steam power and it easy to see how old boilers and condensers etc. were abandoned, but what about the diving-bells? The most likely reason was cost and the difficulty of handling them, as they were made of cast iron and must have weighed something in the order of three to five tons. By the mid-nineteenth century many if not most diving jobs on the river Thames were likely being carried out by cheaper, easily deployed, more versatile copper-helmeted divers.

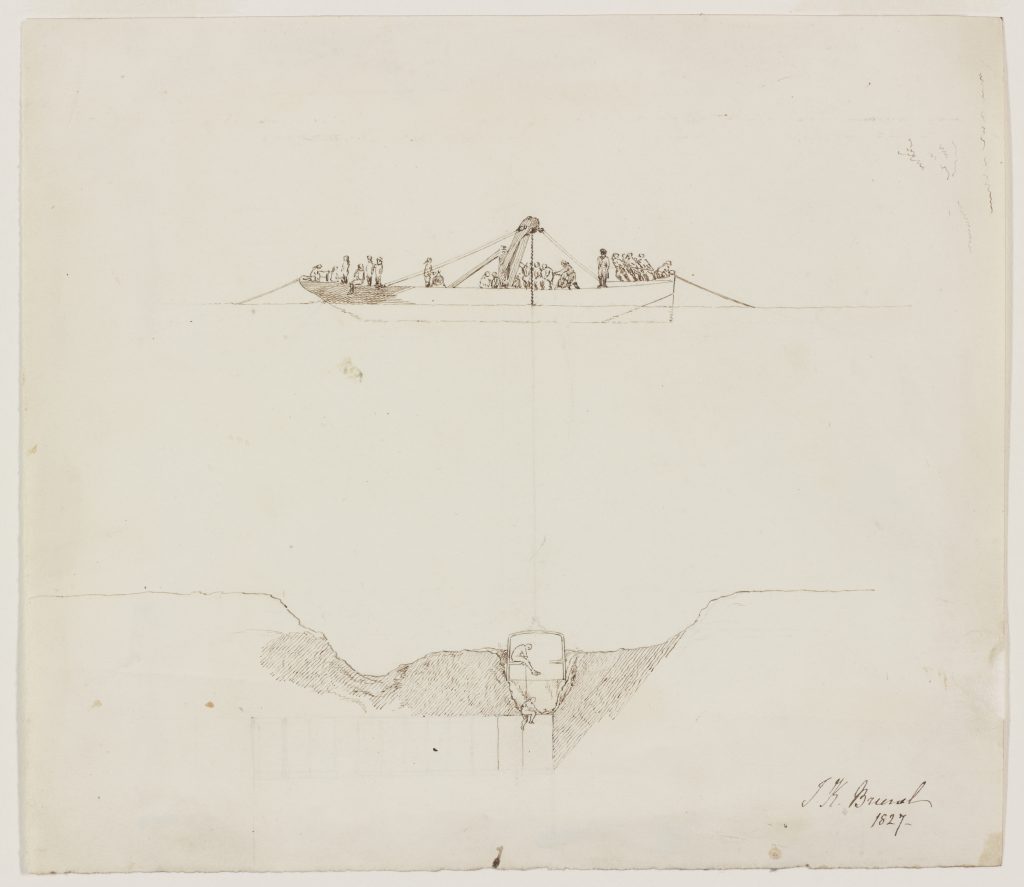

Perhaps the best-known lithograph a diving bell in use on the river Thames is dated 18 May 1827, after the river bed had given way and flooded the tunnel then being dug between Rotherhithe and Wapping. Marc Brunel had begun work in 1825 and made use of a tunnelling shield he had developed together with Thomas Cocrane. But, as the tunnelling approached mid-steam, worries arose when odd pieces of china, glass and bone etc. began dropping into the shield from the river bed above. A diving bell was brought over the site and Brunel, very much a hands-on engineer, descended and found they could touch the frames of the shield below by prodding down into the mud with an iron pipe.

After the flooding on the 18 May 1827 he again descended in a bell to view the damage, together with Michael Faraday (the man who discovered electomagnetism etc., which is why we have computers today). Brunel even jumped into and under the water from the bell to find out how deep the hole was in the river bed, and had to be fished out. A lithograph of that bell, duly dated, was the work of Clarkson Frederick Standfield (1793-1867), a well-known marine artist. He gave his name to the ‘lighter’ on the left, while centre picture is a boat carrying what look like bundles of small branches to fill the hole in the river floor. Could the prominent figure on the right be Marc Brunel?

The hole in the river bed was filled, water cleared from the tunnel, and Brunel held a dinner party there for a group of friends and the tunnelling work went on. Until, that is, the tunnel flooded again later in 1828. Marc’s better-known son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, eventually took over the work, but the tunnel flooded again twice in 1837, once in 1838 and once in 1840, before it was finally finished in 1843.

After the first 1828 episode, there can be little doubt that a diving bell was on more or less permanent on standby until the tunnel was finished. After that is could well be one of the bells relegated the marshy ground alongside Millbank prison. A sad end, after a job well done.