In this blog, Jack Hayes (Collections Access Coordinator), examines a little-known archive detailing the early career of Gilbert Blount, who worked under Marc Brunel between 1840-42. Far from being the perfect job, working life at the Tunnel seems at times to have been a little disorganised, and quite stressful – though undoubtedly Blount’s experience working on the project was foundational for his later career.

Our knowledge of the Thames Tunnel comes primarily from the detailed records kept by Marc Brunel (1769-1849), his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-59), and the diaries and reports of the other engineers who worked on the project.[1] As such, histories of the Tunnel have largely been written from the perspectives of those at the very top. What of the many others who worked on the project? At the Museum, we are currently developing our knowledge of the various individual professions whose efforts enabled the construction of the world’s first tunnel beneath a navigable river, from miners, bricklayers, and blacksmiths working on the construction itself, to the draughtsmen and others working above ground. In most cases, as these individuals left little or no written records, our faint knowledge of them must be gathered through careful and attentive readings of their employers’ reports.[2]

Exceptionally, however, substantial records of one of Brunel’s superintendents, Gilbert Blount (1819-76), have survived. Catalogued for the first time in 2022 by staff at Brunel University Library, Blount’s letters, diary, and papers provide an insight into the day-to-day work of someone other than the well-known resident engineers. Though we must bear in mind that Blount — who leveraged his privileged upbringing to get on at the Tunnel — was still not typical of the bulk of the Tunnel workers, they provide substantial new information on life as Brunel’s employee.[3]

The Blount archive is crucial for a number of reasons. Importantly, it reminds us that Isambard Kingdom Brunel was not the only person to begin his career on the Thames Tunnel: the project began a number of developing careers, including that of Blount, who went on to become an architect. However, it also shows us that the Tunnel Company and Marc Brunel were not particularly excellent employers; through the papers, Brunel sometimes appears somewhat disagreeable, in contrast to claims that he and his son were well-loved by those in their employ. The Thames Tunnel Company itself seems, on the whole, a little more disorganised than we might generally assume.

Getting the Job

Gilbert Blount was employed on the Thames Tunnel, his first job, in summer 1840 at the age of 22. The circumstances of Blount’s first engagement on the Tunnel are hazy. However, his father knew Benjamin Hawes – Brunel’s son-in-law and Chairman of the Thames Tunnel Company – whom he thanked for the ‘patronage’ of his son. It is likely this familial connection was key in ensuring Blount’s employment.[4] Blount thus embarked on work as a superintendent at the Tunnel in a ‘state of probation’, rented a room in Bermondsey, just off what is now Jamaica Road, and was ‘able to set to work in earnest’.[5]

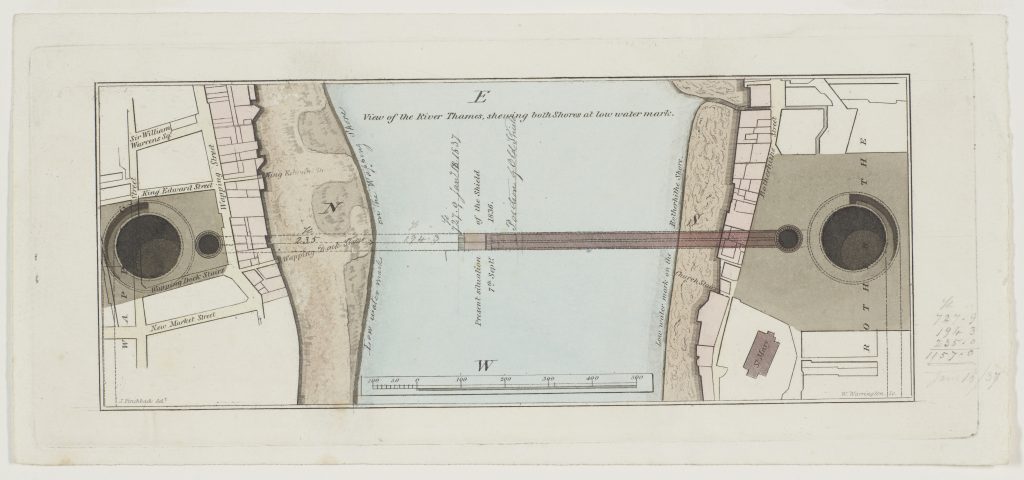

Gilbert Blount’s route to work, from his home in Bermondsey (bottom left circle) to the Tunnel (top right circle), on a map of 1828, via Layers of London (https://www.layersoflondon.org/)

There was soon a rupture between Brunel and his new intern over the question of time off at Christmas. This, Blount’s father noted, had aroused the ‘frowns of Mr. Brunel’.[6] Benjamin Hawes was frank in urging Blount’s father to reconsider the family holiday – both because it would be detrimental to his apprenticeship, and because Brunel would seize on it as a reason to forbid the young man from returning to work. Writing on Christmas Day, as though putting into practice his recommendations not to take holiday, Hawes informed Blount’s father that:

Your son’s absence for a week, so soon, and at such a time, under such circumstances, is just what Mr. Brunel would wish and readily grant — Is pudding & dancing to be put into consideration against a week’s study and attention? — I admit all the delightful sensations of family associations, but success does not depend upon Holidays, but on close study and application to his important profession — I think if he leaves now for a week he will not again return. […] Pray excuse this frank opinion, was he my son he should not leave for a day, he should draw, draw, draw, every day, hour & minute; if any intervals occur, he should read Mechanical Engineering works.[7]

Blount’s father agreed, and his son’s holiday was duly cancelled.[8] This still did not seem to assuage Brunel, as Blount’s father noted a couple of weeks later:

I was in great hopes that you had got a good footing at the Tunnel and that all was going on smoothly, but if Mr. Brunel is determined that you shall not remain, I suppose that you will have to make your bow; however, if you are called before Mr. Hawes and a Board of Directors, be sure that you assent boldly, if asked, that you feel quite equal and willing to superintend any works that are going forward at the Tunnel […] At all event I advise you to remain where you are…[9]

Blount himself claimed to be confused by what Brunel wanted. On 16 January 1841, he wrote to his father that:

Mr. Brunel has just informed me […] that it is not a Draftsman [sic] he wants, but someone to look after the works — This communication, I own, surprised me, as I understood Mr. Brunel was anxious to procure the services of a Draftsman: Pray inform me what I am to do’[10]

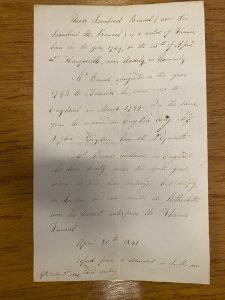

We do not know how the disagreement between Blount and Brunel was resolved, but Blount remained at the works unpaid (with his father paying him an allowance) for many more months.[11] In this period, Blount clearly applied himself to learning, as Hawes had suggested, producing copies of notes by Brunel and others on ‘calculating the power of marine engines’, on the ‘nature of the water flowing into the Tunnel’, on ‘experiments with dowelled timber’, and even on the facts of Brunel’s life and residence in England.[12]

Gilbert Blount’s autograph notes on Marc Brunel’s biography (BLT/3/3, fol. 1r, 3 May 1841, courtesy of Brunel University London, Archives and Special Collections)

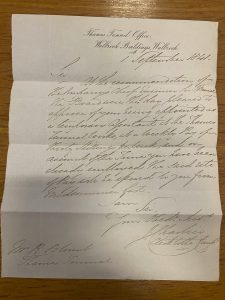

Following another unpaid summer of work for Brunel, in September 1841 Blount was finally employed on a temporary contract as an assistant engineer at a rate of 30 shillings per week.[13] Happily, this included backdated pay at the same rate from ‘Midsummer last’. Less happily, candles and fuel promised in addition to his salary were not provided; Blount’s pay eventually had to be increased by a third to make up for it.[14]

Joseph Charlier’s letter to Gilbert Blount, informing him he had been temporarily employed on the Tunnel (BLT/1/1, fol. 1r, 1 September 1841, courtesy of Brunel University London, Archives and Special Collections)

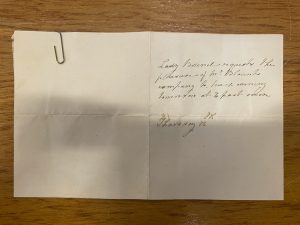

An autograph invitation from Sophia Kingdom, wife of Marc Brunel, asking Blount to tea, most probably dates to this period.[15] While she did not work in an official capacity on the Tunnel, Sophia Kingdom clearly took an interest in the men hired by her husband, and so took the opportunity of Blount’s employment to meet with him one-on-one. It is reported that Sophia had devised a mechanism for delivering nocturnal reports from Tunnel staff to her husband, which she herself operated. Blount would have been one of those responsible for producing and delivering these reports, and so a working relationship between Blount and Brunel’s wife was likely beneficial.

Sophia Kingdom’s autograph note to Gilbert Blount inviting him for tea, (BLT/1/10, fol. 1r, 16 September 1841, courtesy of Brunel University London, Archives and Special Collections)

Daily Working Life

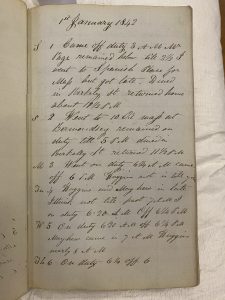

Soon after he was officially employed, Blount used his salary to purchase ‘a new pair of tunnel boots’ for work — clearly a key piece of kit for working underground.[16] As an assistant engineer and superintendent, he had to work long, hard shifts, often extended when tasks had not been finished on time.[17] On Saturday 8 January 1842, Blount arrived at work at 6am, and did not leave until 3am Sunday morning.[18] Other shifts were made longer still by socializing with colleagues. A few days after his long weekend shift, on Thursday 13 January 1842, Blount worked a twelve hour shift at the Tunnel before going to a party held by his boss, Thomas Page (1803-77), which went on until 2.40am.[19] Thankfully, Blount didn’t have to be at the Tunnel on the Friday and he made it to lunch with his brother at 1pm.[20] Just as well: relations between Blount and Page were hardly cordial, with Page having Blount come in early to the office and disapproving of his work.[21] Though he did not always work under him, Blount remained wary. When it seemed he might have permanently to report to Page, Blount admitted in one diary entry that he was not ‘over anxious to be again under Page’s rule’.[22]

First page of Gilbert Blount’s 1842 diary (BLT/2/1, fol. 1r, courtesy of Brunel University London, Archives and Special Collections)

Relations with other colleagues blossomed, however, and Blount became particularly close to another young man embarking on his first job, Henry Law (1824-1900).[23] In December 1840, Brunel had placed Blount into his office alongside a ‘young man’ whom Brunel considered ‘so clever’.[24] This was Law who, like Blount, was from just outside Reading — a lucky occurrence as far as Blount’s father was concerned, though he suspected Law would be his son’s competition for a promotion:

I feel rejoiced that old Brunel is softening down, and I consider it a lucky circumstance that the young chap in his office is a countryman of ours, as he must more or less know who we are, is he the person for whom Brunel wants the situation of Draughtsman?[25]

Competition aside, Blount and Law began taking breaks together outside work, and undertook to read and discuss works on engineering, just as Benjamin Hawes had suggested. In early February, the pair spent a week reading James Smith’s Panorama of Science and Art (1813). Then, Law obtained a copy of Thomas Tredgold’s The Steam Engine (1827) and they continued on. Their communal reading must have been fruitful, with moments snatched where possible to read: on Tuesday 8 March, Blount reports that Law came to his lodgings to read, before the pair had breakfast and went in to work together.[26] It seems the two young men were assiduously following the career advice they had received, and that it did indeed inspire them. Blount reports, for instance, a discussion between the pair on the best methods for ‘describing large ellipses’, noting that ‘these we minutely arranged between us each introducing several important parts’.[27] For Blount, at least, Law was probably a sensible person to be seen to befriend; well-liked by Brunel, we might imagine Blount hoping his study with Law would cause Brunel to see him more favourably.

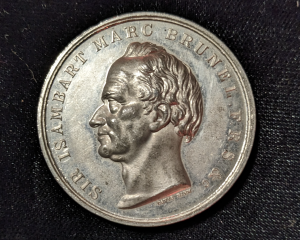

Perhaps any such strategy indeed worked. For all that in 1841 Marc Brunel had been determined that Blount should leave, by 1842 we regularly see Blount coming into contact with Brunel as part of his team. We find Blount sent by Brunel to explain the Tunnel works to a visiting dignitary and being given pieces of work to complete directly by Brunel.[28] One entry for January 1842 states that Blount ‘took several castings’ of Brunel’s profile, an intriguing comment which may imply that the profile of Brunel which appeared on commemorative medals minted from October that year used models produced by Blount.[29]

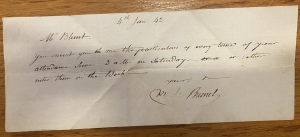

Even so, Blount still slipped up from time to time; one note from Brunel upbraids Blount for not recording his shifts properly. [30] Great attention needed to be given to recording in detail expenditure of various kinds, including salaries — after all, by 1842 the project was funded by the public purse, and well over budget.

Marc Brunel’s autograph note to Gilbert Blount, requesting he properly record his shifts (BLT/1/11, fol. 1r , 4 January 1842, courtesy of Brunel University London, Archives and Special Collections)

The End of the Road

Blount’s temporary employment came to quite a sharp end; he was informed on 12 January 1842 that at a meeting of the Directors, a minute had been passed ‘for effecting a reduction in the Engineer Establishment, and that [his] services as an Assistant’ were to be ‘dispensed with at the expiration of one month from the present time’.[31] Blount, however, disputed the date he was to leave, and refused to be ushered out the door by something so small as the end of his contract, writing that his intention was ‘to remain for the present in [Marc] Brunel’s office should nothing occur to prevent my so doing’.[32] He remained on site for several months – presumably once again without a salary – and continued much as before.

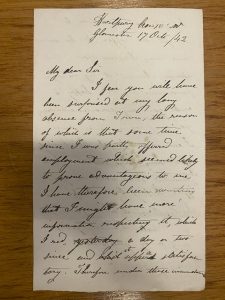

Blount’s intransigence worked and found him fairly steady employ for the rest of summer 1842. However, he ultimately remained dissatisfied – perhaps because really he wanted to be a draughtsman, or perhaps because he received no pay – and ultimately took another job, writing to Marc Brunel on 17 October 1842 to inform him. Blount’s resignation letter strikes a far more conciliatory tone than the dispute of a year earlier would have suggested:

My dear Sir,

I fear you will have been surprised at my long absence from Town, the reason of which is that some time since I was partly offered employment which seemed likely to prove advantageous to me. I have therefore been waiting that I might have more information respecting it, which I received a day or two since and it appeared satisfactory. Therefore under these circumstances I propose to accept the offer; at the same time may I assure you I shall wherever it lay in my power ever be most happy to render you my services when you may require them since I can never forget the kindness I always received whilst in your office. Hoping this will find Lady Brunel and yourself quite well I remain yours very truly,

G. R. Blount[33]

Draft copy of Gilbert Blount’s letter of resignation to Marc Brunel (BLT/1/13, fol. 1r, 17 October 1842, courtesy of Brunel University London, Archives and Special Collections)

Blount’s next role was as apprentice to the architect, Anthony Salvin (1799-1881). This clearly suited him far more, and Blount spent the rest of his career working in that field. A Catholic at a time when there remained much prejudice against Catholics in England, despite the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, Blount came to know key English Catholics including Cardinal John Henry Newman.[34] His work was accordingly and predominantly focussed on Catholic institutions, including designing churches and convents.

Blount died in 1876. While he is absent from published accounts of the Tunnel, his papers allow us to re-examine his participation in the project, and provide insight into working methods of those employed by Brunel. They are a key source of information on the Museum’s collections; further research will be published in due course drawing on Blount’s archive and the Thames Tunnel watercolours.

Update, 24 June 2025: To find out more about Blount’s diary and the production of watercolours, see this blog by Collections Volunteer Arran Saunders.

With thanks to Katherine McAlpine, Director of the Brunel Museum, who first alerted me to a notice about Blount in the press; and to Tace Fox at Brunel University London Archives and Special Collections, for assistance in accessing the Blount Papers.

References

(In citations of Blount’s papers, punctuation has been lightly modified for legibility and abbreviations silently expanded)

[1] These are held primarily in the Thames Tunnel Collection at the Institution of Civil Engineers, London; and at the Brunel Institute, Bristol (esp. DM162/1, DM162/2 and DM1306). See here for a description of the collection.

[2] By and large, this is probably because many were illiterate; see, for instance, the 1826 will of John Hancock, ‘late watchman at the Thames Tunnel’ signed by Hancock with a cross as he was unable to write his own name (National Archives, London, PROB 11/1713/103).

[3] Brunel University, London, BLT/1, BLT/2, and BLT/3.

[4] BLT/1/5, fol. 1v (Michael Joseph Blount to Benjamin Hawes, minute, 22 December 1840).

[5] BLT/1/5, fol. 1v-2r (Michael Joseph Blount to Benjamin Hawes, minute, 22 December 1840).

[6] BLT/1/5, fol. 1v (Michael Joseph Blount to Benjamin Hawes, minute, 22 December 1840).

[7] BLT/1/6, fols 1r-1v (Benjamin Hawes to Michael Joseph Blount, copy, 25 December 1840).

[8] BLT/1/6, fol. 1r (Michael Joseph Blount to Gilbert Blount, 27 December 1840); BLT/1/6, fol. 2r (Michael Joseph Blount to Benjamin Hawes, copy, 26 December 1840).

[9] BLT/1/7, fols. 1r-2r (Michael Joseph Blount to Gilbert Blount, 16 January 1841).

[10] BLT/1/8, fol. 1r (Gilbert Blount to Michael Joseph Blount, copy, 16 January 1841).

[11] BLT/1/1, fol. 2r (11 Jan 1842): ‘Got possession of a new pair of tunnel boots which I had ordered about a fortnight’.

[12] BLT/1/7, fol. 2v (Michael Joseph Blount to Gilbert Blount, 16 January 1841): ‘If you want money, let me know & I will send you some’.

[13] BLT/3/1 (‘Some experiments on dowelled timber by Sir Isambard’ [post-March 1841]); BLT/3/2 (‘Report on the nature of the water flowing into the Tunnel at the head’ [spring 1841?]); BLT/3/4 (‘Method of calculating the power of marine engines’ [April 1841]); BLT/3/3 (‘Facts of Sir I. Brunel’s life’ [3 May 1841]).

[14] BLT/1/1, fol. 1r (Joseph Charlier to Gilbert Blount, 1 September 1841): ‘At the recommendation of the Company’s Chief Engineer Sir Isambard Marc Brunel the Board were this day pleased to approve of your being appointed as a temporary Assistant at the Thames Tunnel works, at a weekly Pay of thirty shillings per week; and on account of the Time you have been already employed the said rate of Pay will be issued to you from Midsummer last.’ See also BLT/1/2 (Joseph Charlier to Gilbert Blount, 1 September 1841). For Brunel’s recommendation, see Institution of Civil Engineers, London, TT/CE/4, fol. 89v (Marc Brunel to Directors of the Thames Tunnel Company, 1 September 1841).

[15] BLT/1/3, fol. 1r (Joseph Charlier to Gilbert Blount, 21 October 1841): ‘I am happy to inform you that the Board yesterday in consideration of your not receiving fuel & candles from the Company’s works in kind, have authorized you being paid henceforward an additional 10 shillings per week in lieu thereof’. For Blount’s acknowledgement of the raise, see BLT/1/4.

[16] BLT/1/10 (Sophia Kingdom to Gilbert Blount, 16 [September 1841]): ‘Lady Brunel requests the pleasure of Mr. Blount’s company to tea & evening tomorrow at ¼ past seven. Thursday 16th’. Marc Brunel was knighted, affording his wife the courtesy title Lady Brunel, in March 1841. This note must therefore be dated either Thursday 16 September 1841, or Thursday 16 June 1842. Given Blount was officially employed in September 1841, this seems the most likely date.

[17] e.g. BLT/2/1, fol. 3r (18 January 1842): ‘Went on duty 6 ½ AM came off 9 ¾ PM. The bricklayers building the piers was the cause of my remaining on duty beyond 6 PM’; BLT/2/1, fol. 5r (1 February 1842): ‘On duty 6 ½ AM off 10 PM men proceeded to hoist the shield’.

[18] BLT/2/1, fol. 1r (8 January 1842).

[19] BLT/2/1, fol. 2r (13 January 1842).

[20] BLT/2/1, fol. 2v (14 January 1842).

[21] e.g. BLT/2/1, fols 12v-13r (21 March 1842): ‘Page sent for me to go in the office to get him some plans before I had breakfast. Made a drawing for the internal mouldings of [the Shaft’s] superstructure in the Tuscan proportion of which Page did not approve’

[22] BLT/2/1, fols 13v-14r (29 March 1842).

[23] ‘Obituary: Henry Law’, Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers 142 (1900), 362-63, https://doi.org/10.1680/imotp.1900.18800.

[24] BLT/1/6, fol. 3r (Gilbert Blount to Michael Joseph Blount, copy, 21 December 1840). Brunel indeed believed this, writing to Joseph Charlier that Law was ‘not only highly competent […] but a most industrious young man’ and recommending he receive a salary of one guinea per week (Marc Brunel to Joseph Charlier, 22 July 1840, Institution of Civil Engineers, London, TT/CE/4, fol. 31r).

[25] BLT/1/6, fol. 2v (Michael Joseph Blount to Gilbert Blount, 27 December 1840).

[26] BLT/2/1, fol. 11r (8 March 1842): ‘Rose 6 ¼ AM Law came 7 ¼ we commenced to read Tredgold together we also had breakfast and went in to office 9 ½’

[27] BLT/2/1, fols 10r-10v (5 March 1842).

[28] BLT/2/1, fol. 12r (16 March 1842).

[29] BLT/2/1, fol. 4r (26 January 1842).

[30] BLT/1/11, fol. 1r (Marc Brunel to Gilbert Blount, 4 January 1842): ‘4th Jan. ’42. Mr Blunt [sic], you must give me the particulars of every time of your attendance since 3 AM Saturday or rather enter them in the Book — Yours etc. Marc Isambard Brunel’

[31] BLT/1/12, fol. 1r (Joseph Charlier to Gilbert Blount, 12 January 1842).

[32] BLT/2/1, fol. 6v (12 February 1842): ‘Last Wednesday having been the end of the month was the day of my nonengagement on this work but I consider it fairly up today this being the time I am paid to. My intention is to remain for the present in Sir Isambard Marc Brunel’s office should nothing occur to prevent my so doing.’

[33] BLT/1/13, fol. 1r (Gilbert Blount to Marc Brunel, draft copy, 17 October 1842).

[34] cf. e.g. University of St. Andrews Libraries and Museums, St. Andrews, MS 38348/B/1/10/2 (John Henry Newman to Gilbert Blount, 28 April 1867).