Tucked amongst the collection of Thames Tunnel memorabilia on display in the Brunel Museum is a small ceramic vase depicting a couple and their countryside cottage. It has a single, thin hollow stem, formed from a tree growing behind the cottage. Unlike all the other examples of Tunnel memorabilia at the Brunel Museum, it does not depict the Tunnel.

Its only obvious connection to the Tunnel is a small inscription on the base: A Present from the Thames Tunnel.

What is it? What is it for? Many people have asked whether it is a vase, but have been slightly confused because there’s clearly not room for many flowers!

In fact, it’s not intended for flowers at all…

Gas Lighting vs. Candles

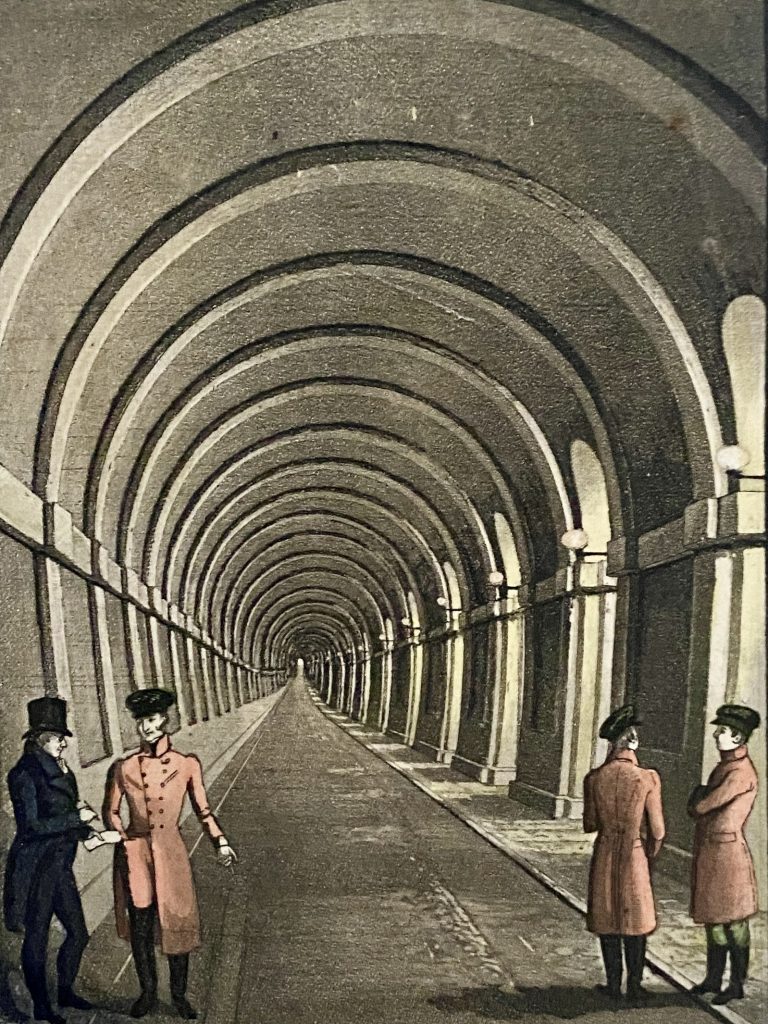

‘A View of the Western Archway of the Thames Tunnel’. Robert Cruikshank and M. Dixie, c. 1828. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2024.10 (detail).

Expecting a dark, underground passage, visitors were often impressed to find the Tunnel was brightly lit. The gas lighting used acted as a special draw to visitors. When the Tunnel works reopened to visitors following a flood in 1828, Brunel noted in his diary that ‘The tunnel was opened to the public and lighted again with our gaz [sic]. All looking very well again’.[1]

Visitors agreed: one described the Tunnel as looking ‘very welcoming for there are plenty of gas-lights’.[2] Indeed, the Thames Tunnel Company noted the extensive gas lighting very prominently in adverts, while the man who supplied the Tunnel’s gas meters also used his link to the Tunnel to promote his business.[3]

When they returned home, however, most people had no gas lighting. Since electricity wasn’t available in the 1840s either, many still relied on fire to light their homes. Candles were so important that they were even provided to some of those who worked at the Tunnel in addition to their salaries.[4]

When you light a candle or a lamp, you need to be able to transfer fire from one place to another, such as from a fireplace to a lamp. Nowadays, we’re used to using matches, which both produce fire and move it to where we need it. While matches were available in the 1840s, they were fairly expensive.

The most common and cheapest method used to light candles and lamps was spill. Spill is a generic term for either small rolls of paper or very thin pieces of wood. Given its importance, spill needed to be on hand at all times for various household necessities. It made sense, then, to keep spill stored neatly but quickly available.

The solution?

A spill vase like this one! The vase has a flat back so it could be placed on a mantelpiece and sit neatly against the wall, ready for use.

Many spill vases depicted recognizable couples, with subjects taken from plays, poems, and novels.[5] In some cases, they acted as promotional material. While some spill vases depict engineering triumphs such as new railways, that is not what this one seems to be doing![6] It is unclear who or what this vase represents: further work is ongoing to identify the subject.

What this spill vase reminds us is that there was a big disparity between the Tunnel and most people’s homes. Most of the millions of visitors to the Tunnel would have been used to more traditional forms of lighting such as candles. The grand lighting used in the Thames Tunnel, a space where many expected to find darkness, would have been particularly exciting.

Browsing the Tunnel’s stalls under the bright gas lights, visitors would have spotted this spill vase and, perhaps, hoped it would transfer some of the bright lights of the Tunnel into their own home.

Book tickets here to visit the Brunel Museum and see the spill vase and other memorabilia sold in the Thames Tunnel.

Full electric lighting is in use throughout!

Bibliography

[1] Institution of Civil Engineers, London, TT/BD/3 (26 May 1828).

[2] Max Schlesinger, Wanderungen durch London. 2 vols (Berlin: Franz Dunker, 1853), vol. 2, p. 24 (‘ganz Freundlich […], den er ist vortrefflich mit Gas erleuchtet’).

[3] See British Museum, London, 1880,0612.403; and ‘N. Defries, Engineer, Inventor’, The Journal of Gas Lighting 1 (10 Feb. 1849), p. 22 (‘two large [gas] meters have been in action at the Thames Tunnel night and day for five years’)

[4] cf. e.g. Brunel University, London, BLT/1/3, fol 1r (Joseph Charlier to Gilbert Blount, 21 October 1841).

[5] See e.g. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, S.1653-2014 (depicting the opera La Fille du régiment); and S.941-1996 (depicting Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale).

[6] For a railway spill vase, see e.g. Science Museum, London, 2017-2015.