25 April 2025 marks the 255th anniversary of the birth of Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-1849) in a small village in northern France. To celebrate, Jack Hayes looks at the connection between Brunel’s birthday, his unusual name, and a medieval knight.

During the Easter holidays, one of our youngest visitors had a specific question about the engineer who built the Thames Tunnel, on the site of which the Brunel Museum is located. Pointing at an image of Marc Isambard Brunel, he asked me:

Why’s he called Marc?

If we’d been talking about most other people, I would have been stumped. Often, the reason behind people’s names is unclear, especially when they’re historic, or else we can say little more than that they were probably named after a relative.

In this case, however, we actually know exactly why he got his names! Very helpfully, a letter from Brunel himself explains just that.

But did you know that his name is linked to his birthday?

‘…you ought to know that St Mark’s day is 25 April’

In April 1840, Marc Brunel had just turned 71. One of his oldest friends, a classmate from his youth in France, had written a letter to him for his birthday — but had got the date completely wrong.

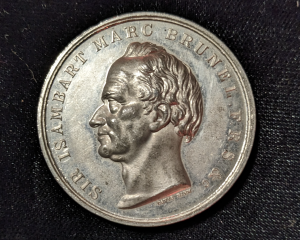

Medal depicting Marc Brunel in profile. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2004.3.

Brunel was quick to point out the error and to explain why the date of his birthday should have been obvious:

I will observe nonetheless that you ought to know that St Mark’s day is 25 April, and that, had I been born on 7 April, my godfather (a devout man) would not have failed to name me after the Saint whose feast falls on that day. Take note then, my boy, that my birthday is 25 April…[1]

St Mark’s Day is 25 April and, according to a long-standing tradition still followed in many countries, Brunel was given the name Mark. Had Brunel been born on 7 April, we’d probably now be talking about the engineer Albert Brunel.[2]

What about Isambard?

Lots of our visitors comment on the unusual name Isambard carried by both Marc Brunel and his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Happily, in the same letter, Marc Brunel also discusses this second part of his name:

Isambard, I should say, means iron beard in German — the name given to a distinguished knight at the time of Charlemagne. I have no idea how it came to be taken over by the Lefèvres. I know only that it passed down from the fourth generation before my godfather…[3]

The Lefèvres were Marc Brunel’s maternal family. Like him, we too have no firm idea why they came to use the name Isambard. Even so, stories about the knight Isambard at the early medieval court of the emperor Charlemagne show why the name might have caught their attention.

Engraved portrait of Charlemagne, late 1500s, by Crispijn van de Passe. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-1907-1937

One of the first biographies of Charlemagne was written by a monk named Notker around 855 AD; it’s largely made up of a series of tales about Charlemagne which emphasise his moral qualities. One tale describes how Isambard, a disgraced knight, killed a wild beast which had torn Charlemagne’s clothing. Charlemagne then showed the horns of the beast and his torn clothing to his wife Hildegarde. She urged him to restore all of Isambard’s privileges in recognition of his bravery, and he did so.[4] This very old story then reappeared in more easily accessible works of general history such as the widely-republished History of France (1713) by Gabriel Daniel.[5]

Whether the tale is true or not isn’t the point: it’s clear why stories like that, connected with great deeds, changes in fortune, and mythical rulers of France, would have appealed. And so the name stuck, and was passed down too to Brunel’s son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Isambart Marc Brunel?

Nowadays, we refer to the man who built the Thames Tunnel as Marc Brunel, to help distinguish him from his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

This wasn’t the case during Marc Brunel’s lifetime. Since Marc is just the name of the Saint of 25 April, he tended to use the name Isambard; he often also inverted the order of his first names.[6] On top of that, he used two different spellings of his name (Isambard and Isambart), though he claimed a preference for the spelling with a t.[7]

This sometimes makes life a bit harder when we’re looking at historic sources! It also means Brunel’s name can look a little bit odd.

Next time you visit the Museum, look out for a small plate with an image of Marc Brunel on display in the gallery. His name is written as ‘Sir J. M. Brunel’:

It’s not an error! Historically, the letters j and i were pretty much interchangeable. So too, as we’ve seen, were the names Marc and Isambard.

In fact, then, what’s written on this plate is probably closer to how Brunel would’ve thought of himself: as Isambart Marc Brunel.

References

[1] Marc Isambard Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 6 May 1840, Archives départementales de l’Eure, Évreux, côte 3F/488: ‘Je l’observerai néanmoins que tu devrais savoir que le jour de St Marc est le 25 d’avril et que mon parain (un Ortodoxe) n’aurait pas manqué de me donner le Saint du jour si j’étais né le 7 —— apprends donc mon garçon que le 25 est mon anniversaire…’

[2] While 7 April is now a feast day of multiple saints, at the time of Brunel’s birth in 1769 the most likely option then available would probably have been St. Albert of Tournai (1060-1140).

[3] Marc Isambard Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 6 May 1840, Archives départementales de l’Eure, Évreux, côte 3F/488: ‘Isambart je devrais écrire signifie en Allemand Barbe de Fer — le nom qu’un chevalier distingué du tems [sic] de Charlemagne portait — mais comment il a été envahi par les Lefevres [sic], c’est ce que j’ignore seulement qu’il a passé de 4ème génération avant celle de mon Parain…’

[4] Notker Balbulus, Gesta Karoli Magni, II.8, in Einhard and Notker the Stammerer, Two Lives of Charlemagne, trans. by Lewis Thorpe (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., 1969), p. 145.

[5] Gabriel Daniel, Histoire de la France depuis l’établissement de la monarchie françoise dans les Gaules. Tome premier (Paris: Denis Mariette, 1713), p. 517. Voltaire, writing in 1753, noted that these early works had formed the basis of almost all histories of France covering this period, cf. Annales de l’empire depuis Charlemagne, 2 vols (Basel: Jean-Henri Decker, 1753-4), vol. I, p. 53.

[6] A letter following Brunel’s knighthood makes clear that he saw this as his name, as he informed his friend of his new style: ‘For me, the form is Sir Isambart Brunel‘ (‘Pour moi, c’est Sir Isambart Brunel’, Marc Isambard Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 3 April 1841, Archives Départmentales de l’Eure, Évreux, côte 3F/488). See also the diaries of Gilbert Blount, which refer exclusively to ‘Sir Isambart’, e.g. Brunel University Library and Special Collections, London, BLT/2/1, fol. 6v (12 February 1842): ‘My intention is to remain for the present in Sir Isambard Marc Brunel’s office’.

[7] Marc Isambard Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 1 Sept. 1839, Archives Départmentales de l’Eure, Évreux, côte 3F/488: ‘In actual fact, my name is Isambart‘ (‘mon nom dans le fait est Isambart‘). This letter is signed ‘Isambard the First’ (‘Isambard 1er’).