As is well known, an intrepid group of pilgrims left Rotherhithe for the New World in 1620. Since then Americans have been returning to England, in growing numbers, to see for themselves where the adventure first began, and where their family roots lie.

Some returning Americans have unusual histories. One of the first Americans to look for family in England was actually a Frenchman. He was a staunch royalist, and fled France as the flames of Revolution were being kindled. A lieutenant in the French navy, he had some useful contacts that helped him get a passage aboard the American ship Liberty, bound for New York. His name was Marc Isambard Brunel.

Brunel arrived in New York on 6 September 1793, and quickly made his mark as an engineer and architect. His first venture, with two fellow émigrés, was to survey the area round Lake Ontario. At the time this was virtually virgin territory. On his return he met Thurman, an American, who engaged him to survey the course of a projected canal to link the River Hudson with Lake Champlain.

Brunel is also one of the few people ever to hold American and British citizenship, and could boast a successful career in both countries. Once he accepted American citizenship, he was appointed Chief Engineer of New York. Amongst other things he designed a new canon foundry and advised on the defences of Long Island and Staten Island. He also submitted the winning design in a competition for a new Congress Building at Washington, though this proved too expensive to build. It was subsequently modified and took shape as the Palace Theatre, New York, which was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 1821.

More significantly, perhaps, he dined in 1798 with Major-General Hamilton, the British aide-de-camp and secretary at Washington, and over dinner had the idea that made him his first fortune…

At the dinner table was a fellow countryman, M. Delabigarre, who had just arrived from England. Conversation turned to ships and navies, and then to the manufacture of wood blocks for sailing ships. These wood blocks housed the sail ropes. A seventy-four-gun ship of the line needed 1400 blocks. The blocks were made by hand. If we multiply 1400 by the number of commissioned ships in an expanding navy, we begin to get some idea of the problem. Moreover, because the blocks were to subject to storm, sea water, wind, ice and sun, each ship would sensibly set sail with a hold full of replacements for the voyage.

To spell it out, the English navy was producing millions of handmade wood blocks every year, and throwing millions of split and perished items into the ocean. Here was a manufacturing opportunity, and Marc Brunel seized it.

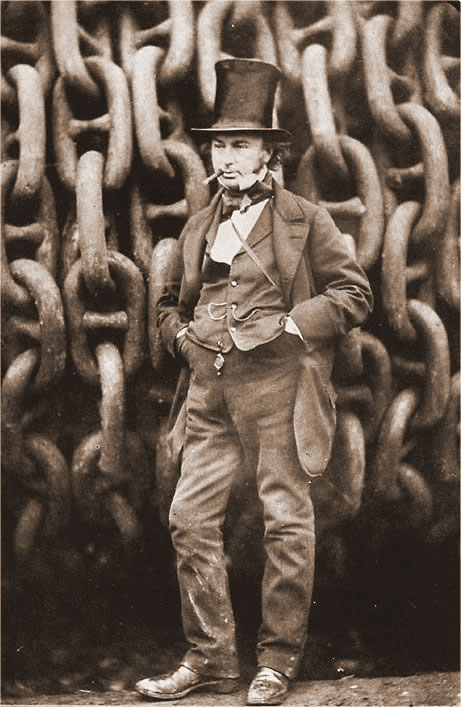

He sailed from New York on January 20 1799, and landed at Falmouth in March, intent on making his fortune. It is not difficult to imagine the suspicion that English officialdom would have had for a Frenchman, from the land of bloody revolution, sailing from America, the land of rebellion. But Marc Brunel had the advantage of an introduction from his friend, General Hamilton, to Earl Spencer of Althorp (Lady Diana’s ancestor: editor’s note). The loyal support of Lord and Lady Spencer were to prove invaluable to the young American, and later to his famous son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Marc Brunel made his first fortune in England from wood blocks; an idea he brought over with him from America. But a fortune was not the only thing he was looking for. Like many Americans of today, he came to England looking for his family…

Unlike many Americans today, he was looking to start a new family, rather than trace an old one. His search was not for ancestors, but for descendants. He came to England looking for the English girl with whom he had fallen in love in France, for he had escaped from revolutionary France with his life, but without his heart. This he had lost to Sophia Kingdom, a young English girl staying with friends in Rouen.

Marc Brunel found his sweetheart in London, married her, and eventually settled in Rotherhithe. Here he began a famous piece of engineering, a tunnel under the River Thames, and the first tunnel under a river anywhere in the world. The story is told elsewhere in these pages, and the London Transport now uses the tunnel, which is incorporated into the world’s oldest underground system.

Rotherhithe rejoices in some obvious connections with the New World, such as the Mayflower pub and the statue of Christopher Jones. But in the Rotherhithe Station, by the entrance to the tunnel, is another commemorative plaque. Erected by the American Civil Engineers and the British Institution of Civil Engineers, it celebrates Brunel’s tunnel as one of the most important civil engineering sites in the world. Today Brunel’s patented method is used universally; workers dig within a protective shield, and build the walls as they dig. Without the principle he established in 1825, none of the underground systems in the world would have been constructed. The Channel Tunnel, linking his country of birth with his country of adoption, would not have been possible.

It is strange to think that this famous American/Frenchman/Englishman ended his journey where some of the first American settlers began theirs. In Rotherhithe Marc Brunel consolidated his career and reputation, founded his family’s success (notably his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel), and was knighted by Queen Victoria.

Londoners are not sure whether to thank America or France for the great gift of Sir Marc Isambard Brunel.