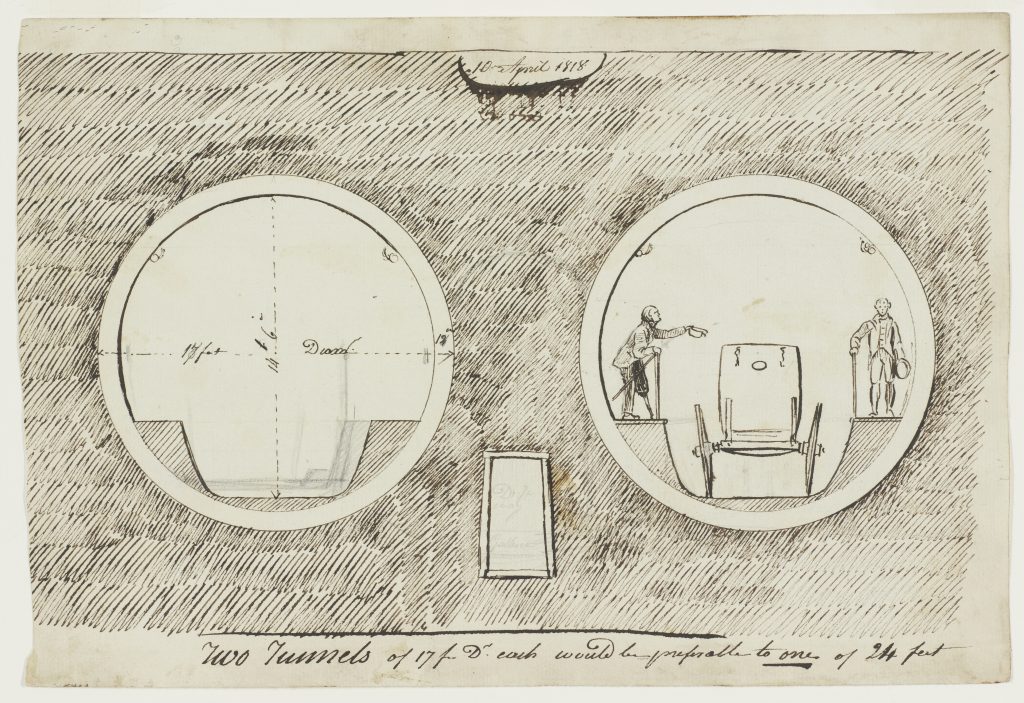

This is a sketch-plan of a proposed tunnel, drawn by Marc Brunel and dated 10 April 1818. Only a few months prior in January 1818, Brunel had submitted his patent for ‘forming tunnels or drifts underground in which he included designs very similar to those drawn here and in LDBRU:2017.10.

On the left side, there is a circular tunnel with annotations showing a 17 foot diameter and internal height of 14.6 feet (accounting for the 12 inch thick walls and slight elevation to level the floor). On the right is a mirror image of the tunnel showing how it was intended to be used: in the centre is a space for horse-drawn carriages, while the sides are reserved for foot access. The much smaller tunnel between the two is to allow for drainage.

This sketch depicts a very early iteration of what eventually constructed, as can be seen by the circular design. In fact, in 1818, Brunel’s design was far from set in stone. It changed substantially in the years between this drawing and when tunnelling started, owing not only to design improvements but also funding issues and changing demands. More details of designs from this time period can be seen in technical drawings such as LDBRU:2017.5.

Perhaps most interesting is what the image reveals about Brunel’s original vision for the tunnel. In the early 1800s, the Thames was the main artery of trade in the capital. However, the boats which facilitated this trade also made it near impossible for a bridge to be built with ample space for masts to pass underneath. This dilemma is why Brunel, and Robert Vazie before him, planned tunnels to allow passage underneath the river. This original concern is why we see such an emphasis on horse-drawn carriages and carts in designs for tunnels from this period, and is no doubt why Brunel favoured two separate streams of traffic. He writes in the caption: “Two Tunnels of 17 f[eet] D[iameter] each would be preferable to one of 24 feet”. In later years, Brunel would shift focus more towards pedestrian access alone. The two men depicted here are interesting characters. The man on the left-hand side is depicted as being from a much poorer background; an amputee, seemingly a veteran, with crutches and begging for money. On the right is what appears to be a much wealthier man holding his hat in his left hand, possibly as a gesture of respect. This choice may have had something to do with Brunel’s previous experience hiring veterans for his boot-making business.

In the early 1800s, technical drawings became valued not only in the workplace but for their ability to communicate designs in the public sphere and to potential investors. Several images associated with the design of the Tunnel show that Brunel was keen to use technical illustrations as a promotional tool to grow a public audience and publicise designs. However, unlike those pieces, this one would not have met the public gaze. As a rough sketch, it shows a much more casual and experimental approach to design; a display of Brunel’s ‘mind’s eye’, that may have instead been shown to only to close contacts.

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.