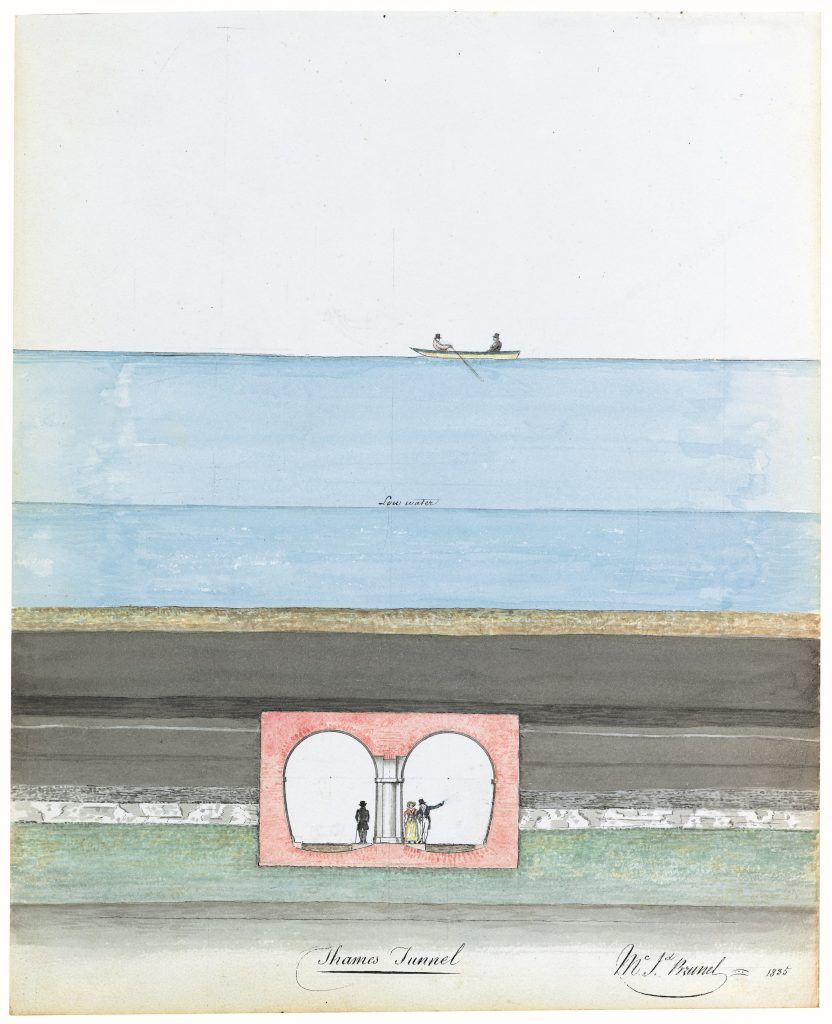

Brunel tunnel watercolour

| Year | 1835 |

|---|---|

| Object no. | LDBRU:2001.2 |

| Size | 180mm (w) x 230mm (h) |

| Location | FS5 - upper floor |

| Acquired | Purchase Art Fund Thomas Williams Fine Art LTD |

A fine water colour of the Thames Tunnel by Sir Marc Brunel, dated 1835