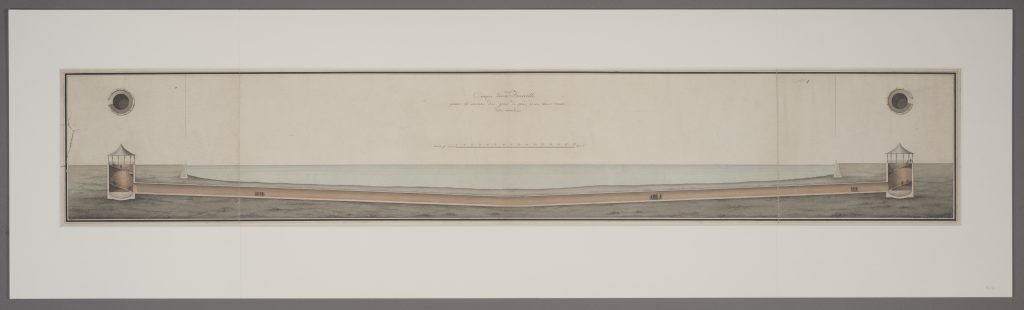

This watercolour illustration, signed and dated by Joseph Pinchback, 1818 (‘Drawn by J. Pinchback, 1818’) shows a cross-section view of an early tunnel design. It is captioned, in Marc Brunel’s hand, ‘Coupe d’une Tonnelle pour le service des gens de pied, prise dans toute son étendue’, or ‘Cross-section of a Tunnel for the use of infantry, shown in its full extent’, and includes a scale of feet.

Brunel’s patent ‘Forming Tunnels or Drifts Under Ground’, published on 20 January 1818, details two tunnelling methods that both take on a circular shape. As shown by the shadowing on the tunnel walls, the tunnel drawn here used one of these early designs as opposed to the rectangular one eventually adopted. On the far left and right of the tunnel are the entrance shafts, drawn with a circular stairway hugging the wall, roof, and bird’s eye view just above.

Interestingly, those using the tunnel appear to resemble soldiers — perhaps Russian, not British, judging by the colour of their uniforms. At this stage, Brunel was still campaigning to build a tunnel, and the Thames was not the only candidate. During the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, Brunel had laid out plans for either a tunnel or a bridge over the River Neva in St. Petersburg. Given the 1818 date of this watercolour, and the use of French – the language of the Russian Imperial Court – for the caption, this watercolour may have been shown to the Tsar and Russian government.

Despite this early iteration, no formal proposal was sent to Russia until December 1820 as Brunel. Although this would eventually be rejected owing to a lack of funds, Brunel’s active correspondence in Russia was likely what saw him released from debtor’s prison less than a year later in 1821.

During the Industrial Revolution, technical drawings had become a popular method for communicating designs and functionality. In the early 1800s, engineers began better to understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for shaping public perception and bringing engineering to the masses. Those intended for the workplace included technical details needed to bring the design to reality. However, pieces like this one differed in that they were created for a more public audience — one without detailed knowledge in engineering practices. As presentation pieces, they appealed to this audience through the use of watercolours and directional lighting, which helped the untrained eye visualise the design, and by omitting any unnecessary and complicating details. These traits, alongside their reproducibility, created a characteristic style that helped bring the industrial world into the public domain.

Brunel was one engineer who used technical illustrations as a promotional tool to grow an audience and publicise designs. This piece dates to 1818, when Brunel was still planning and campaigning for a tunnel, and it would be another seven years until construction of the Thames Tunnel began. These visually appealing watercolours would have played a role in the process of sharing designs and gaining support from investors, as did various illustrations reproduced for pamphlets and publications such as the Mechanics Magazine.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role, and draughtsmen solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.