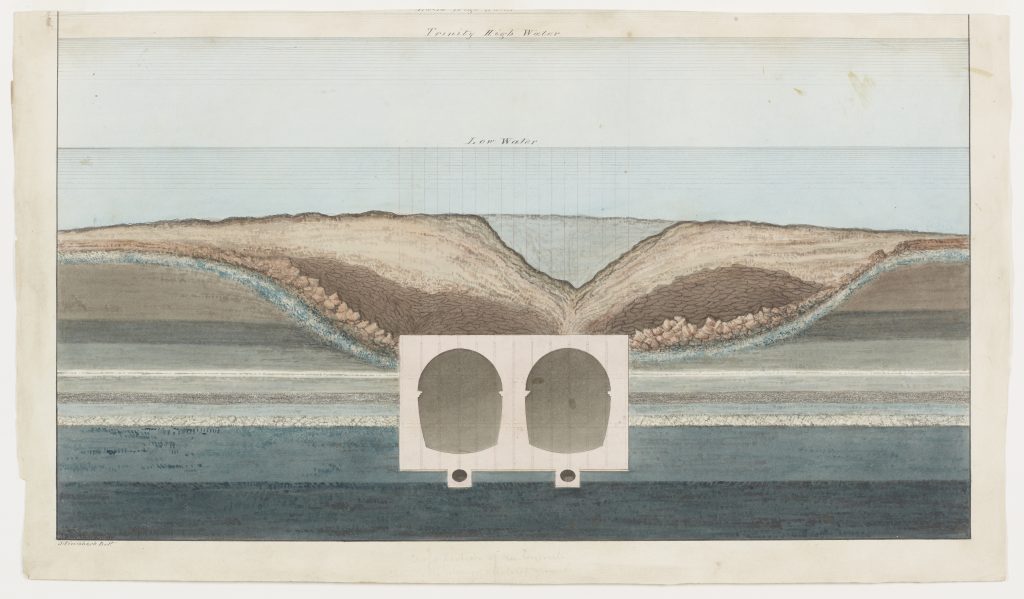

This watercolour shows the effect the first flood of 18 May 1827 had on the riverbed, and is signed by Brunel’s chief mechanical draughtsman, Joseph Pinchback. It is one of several pieces in this collection which show the effects of the first flood. Others include LDBRU:2017.17 and LDBRU:2017.24, as well as Brunel’s descent in the diving bell shown in LDBRU:2017.1.

As the first major flood, this watercolour illustrates a pivotal moment in the tunnel’s story. The tunnel, now 548 ft. long, had met a cavity believed to have been caused by dredging and worsened by the anchors of a series of collier boats. In the weeks preceding the flood, stones, coal, bones, glass and china had been entering the tunnel, but it was on 18 May that the cavity filled with tidal dirt and debris gave way and rushed into the tunnel. There would be another 4 major floods during the tunnel’s construction, the second of which led to nearly a 5 year hiatus in its construction from August 1828 to March 1835.

This illustration in particular shows in great detail the different strata of the riverbed. The bags of clay which were used to plug the intrusion are also visible, as are high and low water markings to display the depth of the tunnel.

This piece seems to have been created with considerable care and effort as a presentation piece for public viewership. It was likely also used as inspiration for simpler yet mass-producible variations appearing in booklets sold at the Tunnel Works and across London, titled ‘Sketches of the Works for the Tunnel Under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping’.

During the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, in the early 19th century, engineers began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for shaping public perception and bringing engineering to the masses.

Brunel and the tunnel are great examples of this. The fact that the tunnel has been drawn here without any visible damage whatsoever suggests Brunel and the Thames Tunnel Company were keen to manage publicity of the incident and preserve reputation. This piece, as well as those which appeared in contemporaneous publications, all drive the narrative that the flooding was a very manageable problem which posed no critical threat to the tunnel, its shield, and its workers.

While technical drawings intended for the workplace included specifics and details crucial for engineers, presentation drawings like this one appeared to the layman with a much more artistic approach lacking technical details. Their reproducibility was central to bringing, in this case, the tunnel firmly into the public domain.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and draughtsmen soon solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.