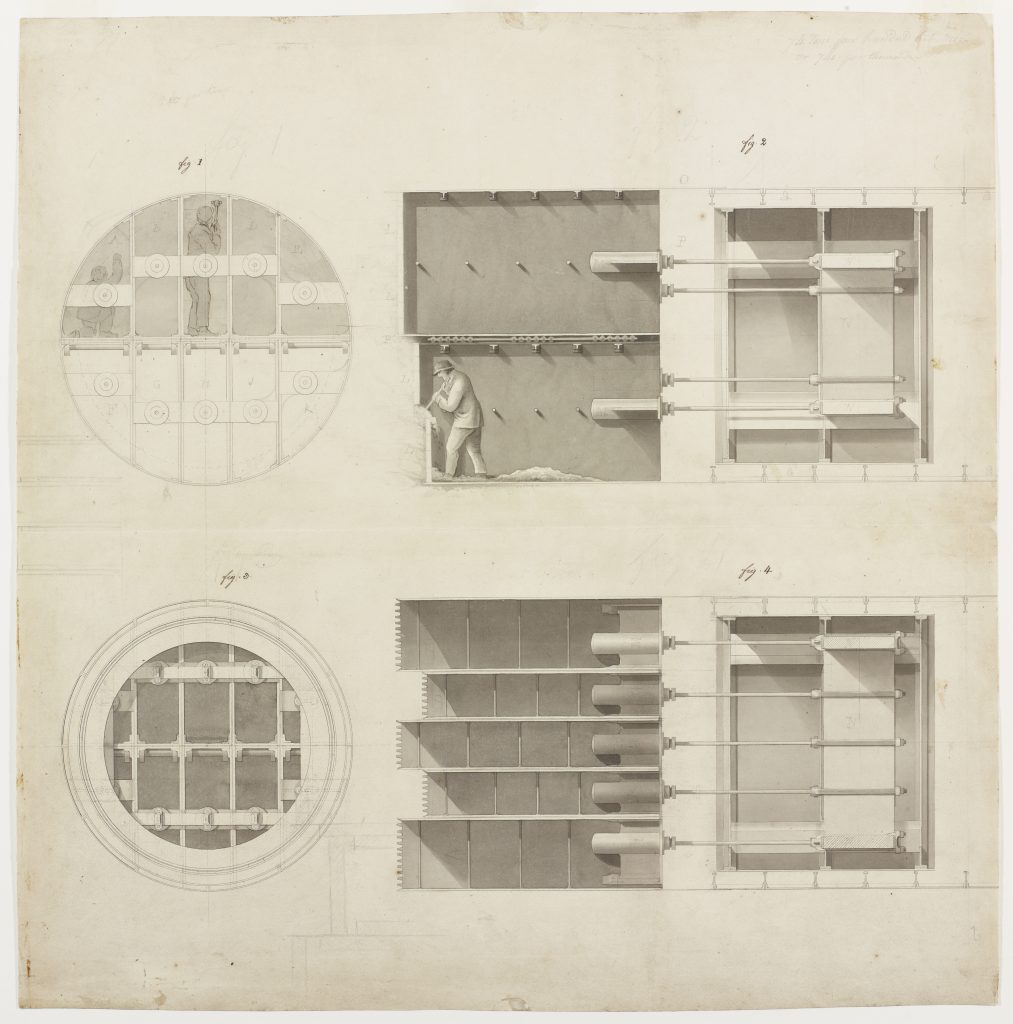

This grisaille watercolour is a technical illustration of one of Brunel’s early designs for the Tunnel, which he likely drew himself. At some point, the page has been cut and squared off.

It is a near-identical version of what appears in Brunel’s Patent no. 4204 “Forming tunnels or drifts underground” from January 1818, in which he described two tunnelling methods. One used a centrally-located auger much like the teredo navalis shipworm, while the other, depicted in these four figures, shows one with a shield made up of several cells for miners to work in.

A design very similar to this one would eventually be used for the Tunnel. Key differences are the circular design, which was eventually swapped for a more rectangular one, the shield being constructed with only two levels rather than three, and the hydraulics system which was replaced with a screw-driven design.

Figure 1 shows a view behind the tunnelling shield. In the patent, Brunel describes this method as a means of securing the excavated earth before it can be lined and hold its own. This casing would also protect the miners: “The workman thus inclosed and sheltered may work with ease and in perfect security.” Time would tell, following several floods, that this was not quite the case, with the second major flood on the 12 January 1828 killing six workers and injuring his son Isambard.

In Figure 2, we see this same shield from a cross-sectional side view. A miner is shown digging away at the front of the shield, with ‘polling boards’ set in place to secure the section not being excavated. We also see the hydraulic press behind, driving the entire shield forwards. The benefit of this design, in Brunel’s words, is that “several men may work at the same time with perfect security and without being liable to any obstruction from each other.” Figure 3 shows a transverse view of the shield, while Figure 4 shows a top down view of the shield with its friction rollers designed to aid the movement of the shield.

The page is also scattered with faint notes and scribbles in Brunel’s hand. On the top right, Brunel writes “74 tons per hundred feet used or 740 per thousand” referring to the iron plates used to secure the structure of the tunnel. Meanwhile, the top left has a note suggesting that the shield could advance at “2 in[ches] per hour”.

Throughout the Industrial Revolution, technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. We can see this here especially as this design was used, and perhaps even created, for a patent. Brunel would also go on to make several similar watercolours as a promotional tool to showcase his designs and ideas to a more public audience (see LDBRU:2017.23, LDBRU:2017.11, and LDBRU:2017.5 for some great examples) . These ‘presentation pieces’ were instrumental in helping Brunel find investors, publicise designs, and build reputation. It was primarily their reproducibility, which can also be seen clearly between this piece and what appeared in the patent, which enabled them to be used in this way.

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.