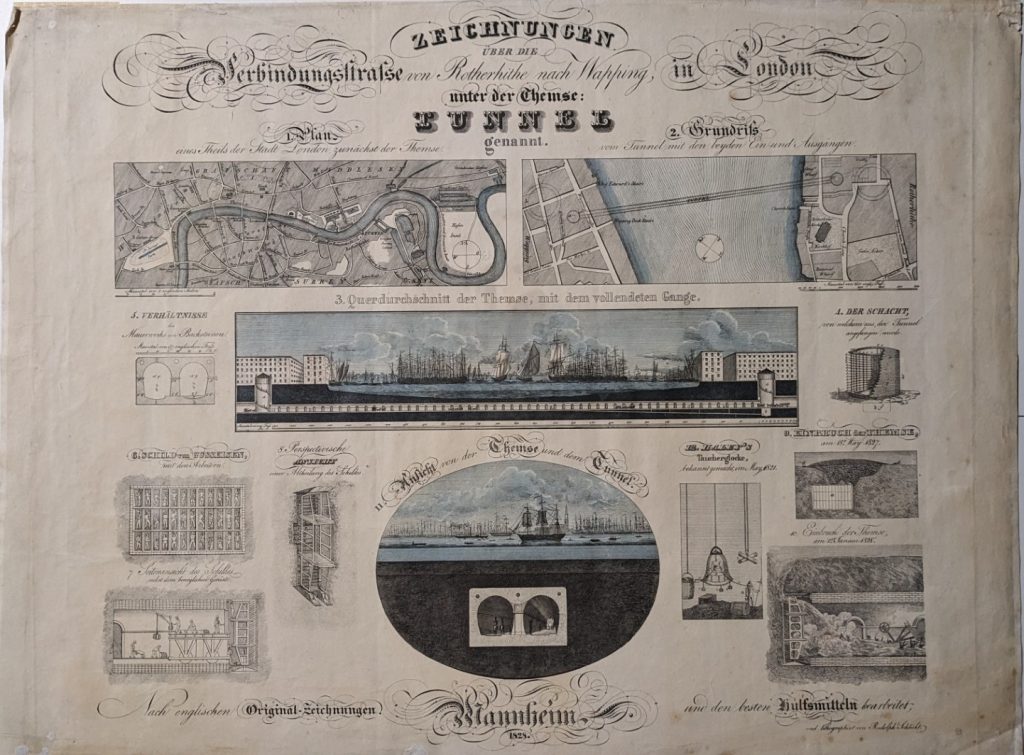

This large printed sheet includes twelve lithographed images of various aspects of the Tunnel, its construction and of the two floods of 1827 and 1828. It was produced by Rudolph Schlicht (died ca. 1847-48), a printer and newspaper editor in the German city of Mannheim, then part of the Grand Duchy of Baden. Entitled Zeichnungen über die Verbindungsstraße von Rotherhithe nach Wapping in London unter der Themse, Tunnel gennant (‘Drawings of the Road linking Rotherhithe to Wapping in London under the Thames, called The Tunnel’), it dates to March 1828, when construction of the Tunnel had paused pending removal of floodwater and the agreement of new funds. The print makes no mention of these difficulties, instead concentrating on Brunel’s technical prowess.

Rudolph Schlicht operated from around 1819 to the mid-1840s. Using the then fairly new technique of lithography which had been invented in Bavaria at the end of the 1700s, Schlicht typically printed maps; this depiction of technical aspects of the Tunnel’s construction is unusual in the context of his wider work. It may be partly explained by Schlicht’s own interest in engineering. In October 1831, Schlicht announced his invention of a new type of lithograph machine. The following year, he published an illustrated description of his invention, for which he was awarded both a patent and a prize from the Grand Duke of Baden. In a review of Schlicht’s published description, the German engineer and professor of mathematics at Heidelberg, Karl Christian von Langsdorf (1757-1834), noted that Schlicht ‘has, through his excellent work, long since made himself known as one of the foremost artists in this field’ and that locals and visitors alike ‘never leave without applauding and admiring his peculiar printing-shop’.

An insight into this print and its audiences is provided by adverts for it placed by Schlicht in newspapers in cities such as Speyer, and by distributors in other cities such as Zweibrücken. Schlicht’s advert in the Neue Speyerer Zeitung on 10 April 1828 announces that the Tunnel is ‘the most remarkable work undertaken in the modern era in the field of architectural science’. While Schlicht admits that his is not the first available print of the Thames Tunnel, he emphasises the reasons why his is the best. While others ‘deal with the subject only partially, or without sufficient detail’, Schlicht’s print based on ‘reliable original materials’ contains twelve different images, ‘faithfully reproduced from English models and accompanied by an explanatory text’. It is unclear how Schlicht acquired such ‘models’, though it is possible he saw one of numerous illustrated reports in circulation in German-speaking territories, including an 1827 pamphlet on the Tunnel published at Leipzig, or a January 1828 German-language Tunnel guidebook, printed in London and then reprinted in Magdeburg and Erfurt. These guidebooks contain twelve lithograph plates, many of which closely correspond to Schlicht’s print; however, the source, or sources, which Schlicht accessed are unknown.

The adverts offered readers the opportunity to purchase the print for a discounted price: black and white versions cost one Bavarian gulden, while coloured copies, such as this one, sold for the higher price of one gulden and 48 kreuzer. By advertising his prints in newspapers, Schlicht targeted middle class audiences who were sufficiently wealthy to purchase and display this print, and who were sufficiently educated to appreciate its content.

Prints such as this were crucial in spreading news of the Tunnel across Europe, circulating alongside peep-shows of the type available in Britain. Foreign interest in English feats of engineering, and the concomitant production and dissimulation abroad of printed imagery of such feats, can be seen in the context of wider nineteenth-century European competition in processes of industrialization. Speyer and Zweibrücken, cities in which this print was sold, were in the Kingdom of Bavaria, which in 1835 became the location of the first railway in Germany. The large format of Schlicht’s print of the Tunnel, with sufficient space for smaller details to be visible, suggests it was designed to be prominently displayed and closely examined, acting perhaps as a stimulation to technical discussions in cities and countries developing their own innovative infrastructure projects.