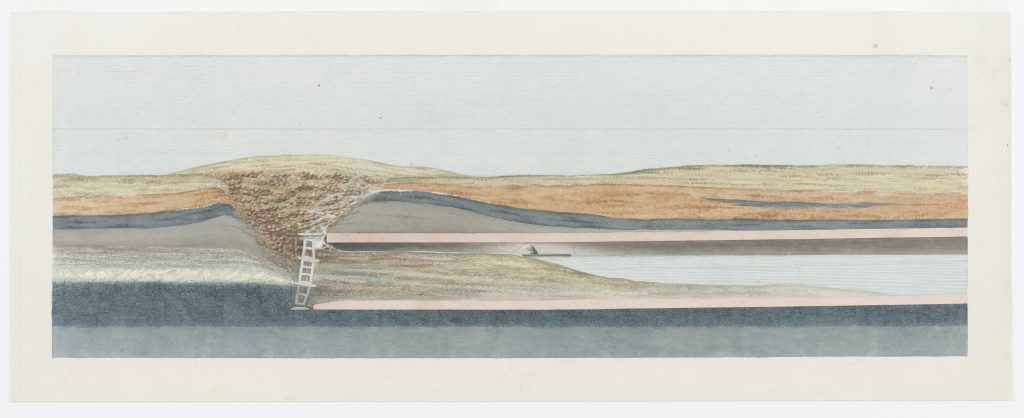

This watercolour shows a longitudinal section of the tunnel with two individuals inspecting the shield after the first flood of 18 May 1827, and is attributable to Brunel’s chief mechanical draughtsman, Joseph Pinchback. It is one of several pieces in this collection about the first flood, with others including LDBRU:2017.16 and LDBRU:2017.24, as well as Brunel’s descent in the diving bell shown in LDBRU:2017.1.

The main focus of the piece is the dirt, debris, and water that had flooded into the tunnel. It’s shown some time after the event in a stable state with the riverbed cavity plugged with clay bags. One man is on the boat with a lamp and the other, Richard Beamish, resident engineer, is shown scrambling on top of the dirt to examine the partially tilted but wholly intact shield. The strata of the riverbed are also artistically painted with watercolours to help visualise how the ground was displaced.

Showing the first major flood, this watercolour illustrates a pivotal moment in the tunnel’s story. Now 548 ft. long, miners had met a cavity believed to have been caused by dredging for gravel and worsened by the anchors of a series of collier boats the previous day. In the weeks preceding the flood, stones, coal, bones, glass and china had been entering the tunnel, but it was on 18 May that the cavity filled with tidal dirt and debris gave way and rushed into the tunnel. There would be another 4 major floods during the tunnel’s construction, the second of which led to nearly a 5 year hiatus in its construction from August 1828 to March 1835.

During the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, in the early 19th century, engineers began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for bringing engineering to the masses and shaping public perception. Those intended for the workplace included specifics and details crucial for engineers, but presentation drawings like this one were designed for the public eye. They lacked any technical detail and aimed to be both visually pleasing and easily reproduced.

Drawings of the first flood like this one were even published in booklets sold at the tunnel and across London, titled ‘Sketches of the Works for the Tunnel Under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping’. Key here is that very minimal damage is shown to the tunnel and the flood has already been successfully rectified. Rather than a disastrous flood, all show an obstacle overcome with brave, triumphant, and even heroic engineers at the forefront. The incident would have been common knowledge, but these images were useful tools to influence the narrative being told and preserve reputation.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and draughtsmen soon solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.