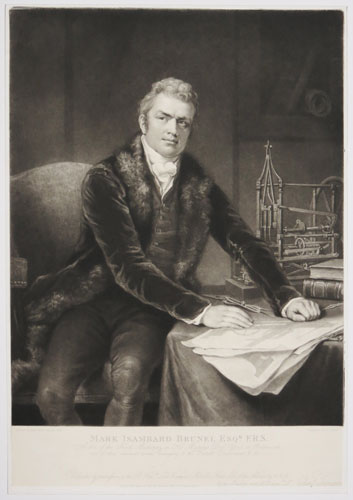

This print depicts Marc Brunel early in his career in Britain, before work had begun on the Thames Tunnel. The print was published on 30 March 1815 by Charles Turner (1773-1857), a London engraver and publisher. The print reproduces a painting of Brunel done in 1812-13 by James Northcote which was first exhibited in 1814, and was later owned by the Brunel family. It is likely Turner negotiated an agreement with Northcote, whose paintings he had previously engraved in 1799 and 1812, to produce this print directly following the exhibition of 1814.

Prints such as this were widely purchased, and variously used: as well as being displayed on walls, they were often collected into albums. They emerged within the context of a new mass market for printed reproductions of paintings, and especially of portraits, which had developed across Britain by the late eighteenth century. This mass market was driven by a burgeoning middle class and an expansion in public access to art. This new market for printed reproductions typically preferred modern English art depicting contemporary subjects. The inclusion of the model of Brunel’s block-shaping machine, designed for the Royal Navy, on the table behind him stands as evidence of his involvement in the contemporary world. At the same time, this printed portrait – which sought to increase Brunel’s public visibility – also participated in his transformation into a ‘gentleman engineer’, amidst a wider shift in the social status of engineers during the early nineteenth century.

Turner produced this print during an important period in the history of engraving in Britain, when the value and status of engraving were the subject of particular debate. Since engravers predominantly reproduced paintings, their work was felt by some to hold little or no artistic value in its own right. As a consequence, the Royal Academy did not admit engravers to full membership, even though engravings were often displayed next to paintings they reproduced during exhibitions. While a petition in 1809 sought to admit engravers to full membership, it was firmly rejected, and as late as 1858 influential figures such as John Ruskin critiqued engravers as mere copyists.

Turner worked predominantly in mezzotint, a technique developed specifically for reproducing oil paintings. A major disadvantage of the technique was that copper mezzotint plates degraded quickly, meaning print runs were smaller than for other forms of engraving. Smaller print runs, however, enabled printers to leverage scarcity value to their advantage. This, combined with the development of more formalised frameworks for obtaining the rights to reproduction afforded by the Engravers’ Copyright Act 1735, enabled printers to market prints as authorised, valuable artworks in their own right. The production of different ‘states’ of a print further enabled the economic rarefication of printed reproductions. This print of Brunel exists in four variant states; the Brunel Museum’s copy is state I.