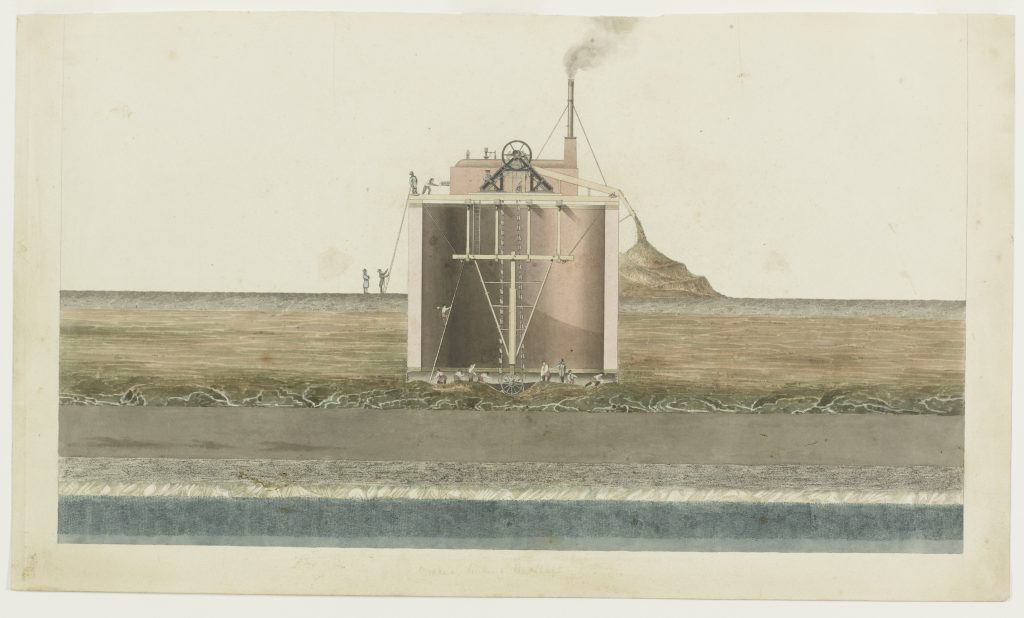

A watercolour cross-sectional illustration of the tunnel shaft, likely done in 1825. On the 16th of February 1825, permission was granted to clear the ground for a sinking shaft 50 feet in diameter and 42 feet in height. Shortly after, on the 3rd of March, the brickwork began and thus marked the beginning of the construction of the tunnel.

This watercolour depicts the shaft mid-way through being sunk. It is attributable to Joseph Pinchback, who was Brunel’s Chief Mechanical Draughtsman, and likely dates to around the same time period. We can see the brick walls of the shaft and the different strata of ground the tunnel had to sink through. Workers can be seen inside digging away and shovelling dirt into a pulley system operated by the steam engine situated at the top of the shaft. A few other well-dressed men oversee the operation.

This piece was reproduced by woodcut in Richard Beamish’s Memoir of the Life of Sir Marc Isambard Brunel captioned “Section of shaft in process of being sunk”. In the memoir, Beamish describes the process in great detail. The shaft (and the wider tunnel project, for that matter) attracted a lot of attention from the general public. As the shaft was being sunk, crowds would come to spectate the site, including high-profile visitors such as the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and the Duke of Wellington.

Throughout the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, in the early 19th century, engineers began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for shaping public perception and bringing engineering to the masses.

While those intended for the workplace included technical details needed to bring the design to reality, pieces like this one differed in that they were created for a more public audience. As presentation pieces, they distilled complex engineering feats into something more approachable by omitting technical details and with a pictorialist use of watercolours and lighting. These traits, alongside their reproducibility, created a characteristic style that helped bring engineering into cultural life and public interest.

Brunel was one engineer who used technical illustrations to do just this. At the very beginning of the project, which was already drawing much public attention, it would have been invaluable to grow an audience, develop his reputation, and strengthen public standing.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and draughtsmen soon solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.