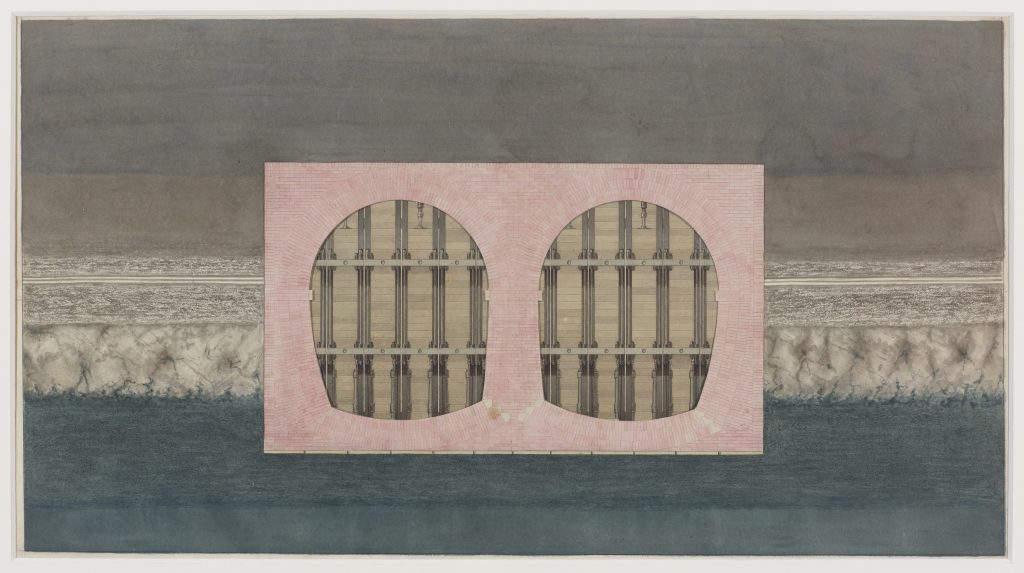

Uniquely, this object is made up of a pair of watercolours intended to be placed on one another. Both show the strata of earth through which the Tunnel was dug, but, where the under section shows the tunnelling shield, the overlay shows the finished brickwork with cutouts in the centre to enable the image of the Shield below to be glimpsed.

Other watercolours held by the Museum made in a similar style are often signed by Brunel’s chief mechanical draughtsman, Joseph Pinchback. This piece, although unsigned and undated, likely had his involvement — although we know from the diaries of another of Brunel’s employees, Gilbert Blount, that it was not unusual for several hands to have been involved in a single drawing even over the span of multiple iterations.

Despite its unclear authorship, the pair of watercolours is believed to be the basis of a mass-produced variant that was included in guidebooks of the tunnel titled Sketches and Memoranda of the Works for the Tunnel Under the Thames, From Rotherhithe to Wapping as early as 1827. It appeared in these publications much like this watercolour version, with an overlay that could be folded in and out to place the brickwork over the tunnelling shield. A cardboard model was made in 1828 with the same principle; clearly, this was a popular method of communicating the method of the Tunnel’s construction in a more visual manner.

Across the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, in the early 1800s, engineers including Brunel began to better understand and appreciate them as a visual medium for shaping public perception and engaging public interest.

Insight into the purpose of the watercolours can be gleaned from certain characteristics in their visual appearance. While those intended for the workplace included technical details needed to bring the design to reality, pieces like this one differed in that omitted technical details and favoured a pictorialist use of colours and lighting. These traits, alongside their reproducibility, indicate that they were produced not for those working on the tunnel but for lay people — be it the general public, investors, or stakeholders. Reinforcing this idea is the fact that an interactive visual display of the tunnel would have been an incredibly powerful tool to capitalise on the interest generated at the start of the tunnel project in the mid to late 1820s.

Over time, technical drawings and illustrations began to play a more prominent role in early 19th century engineering, and draughtsmen soon solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers. Brunel had various employees — both draughtsmen in official capacity and other positions — produce and modify the watercolours in this collection, and their impact to the eventual success of the tunnel should not be understated. In fact, at the same time Brunel was awarded a silver Telford medal in 1838 for his design and communication of the tunnelling shield, Pinchback was given a bronze medal recognising the “beauty of the drawings.”

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.