Would you believe that our hero Isambard Kingdom Brunel was a pioneer of prefabrication?

Doesn’t sound Victorian-style but in times of national crisis some extraordinary things can be achieved. We have recently been amazed by the speed of the herculean task of turning conference centres such as Excel into fully functioning hospitals for high-risk patients. In 1855 Isambard Kingdom Brunel was set a similarly daunting task. To design and create a state of the art modular hospital that could be produced in the UK and then transported and erected on an unknown site in a war zone thousands of miles away. He achieved the entire project in 5 months, here is the story:-

Brunel’s Hospital at Renkioi

On 16th February 1855 after the first winter of the allied armies in the Crimea, Mr. Isambard Brunel was asked by the War Department to undertake the design and construction of hospital buildings to be erected in the Dardenelles. He responded on the same day saying that ‘his time and best exertions would be, without any limitations, entirely at the service of the government’.

He proceeded to design and oversee the manufacture of the required buildings and all their internal arrangements. They were sent out under his supervision and erected at Renkioi. Their use ceased when peace was concluded, but for 7 months they added greatly to the treatment and comfort of 1,300 sick and wounded soldiers.

He laid out four conditions for the construction of the buildings:

- They should be capable of adapting themselves to any plot of ground that might be selected, whether level or on a reasonable incline

- They should be capable of being easily extended from holding 500 patients to up to 1,500 or more

- They should contain every comfort possible under the circumstances

- They should be very portable and of the cheapest construction

Each separate building unit was constructed from wood and made the same size and shape so that with an infinite length of open corridor to connect them, they could be arranged in any form to suit the levels and shape of the ground. A unit consisted of two wards, one nurse’s room, a small storeroom, bathroom, surgery, lavatories and ventilating apparatus.

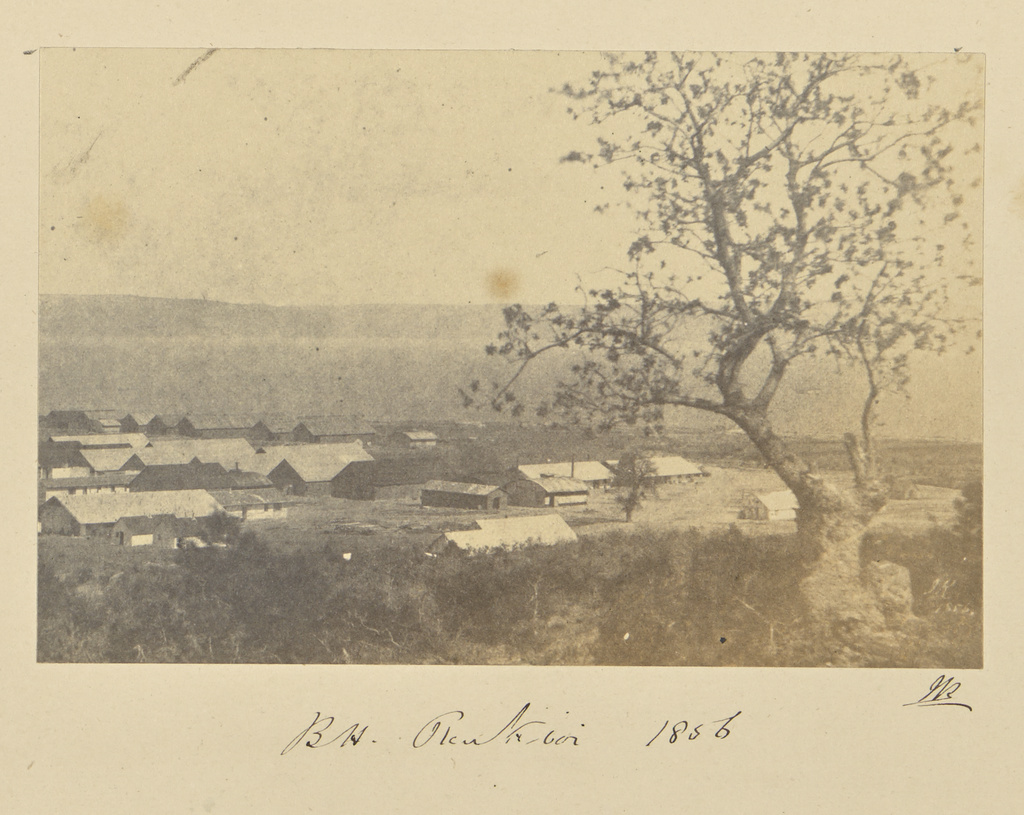

John Kirk, photographer (Scottish, 1832 – 1922), B.H. Renkioi 1856, Scottish, 1856, Albumen silver print, 8.2 × 12.8 cm (3 1/4 × 5 1/16 in.), 84.XA.619.57. Courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

To optimise ventilation in a hot climate, fresh air was forced into each building by a small mechanical fan easily worked by one man and capable of supplying up to 1,500 cubic feet of air per minute.

Air travelled along the centre of each ward rising up through the floorboards and flowing to every part of the room. By forcing the air into the room (positive pressure) it prevented the ingress of bad air from drains, WC’s etc. In addition to this, a very simple provision was made for passing the air over a considerable area of water surface that would not only help to cool it but also reduce the effect of the excessive dryness of the climate.

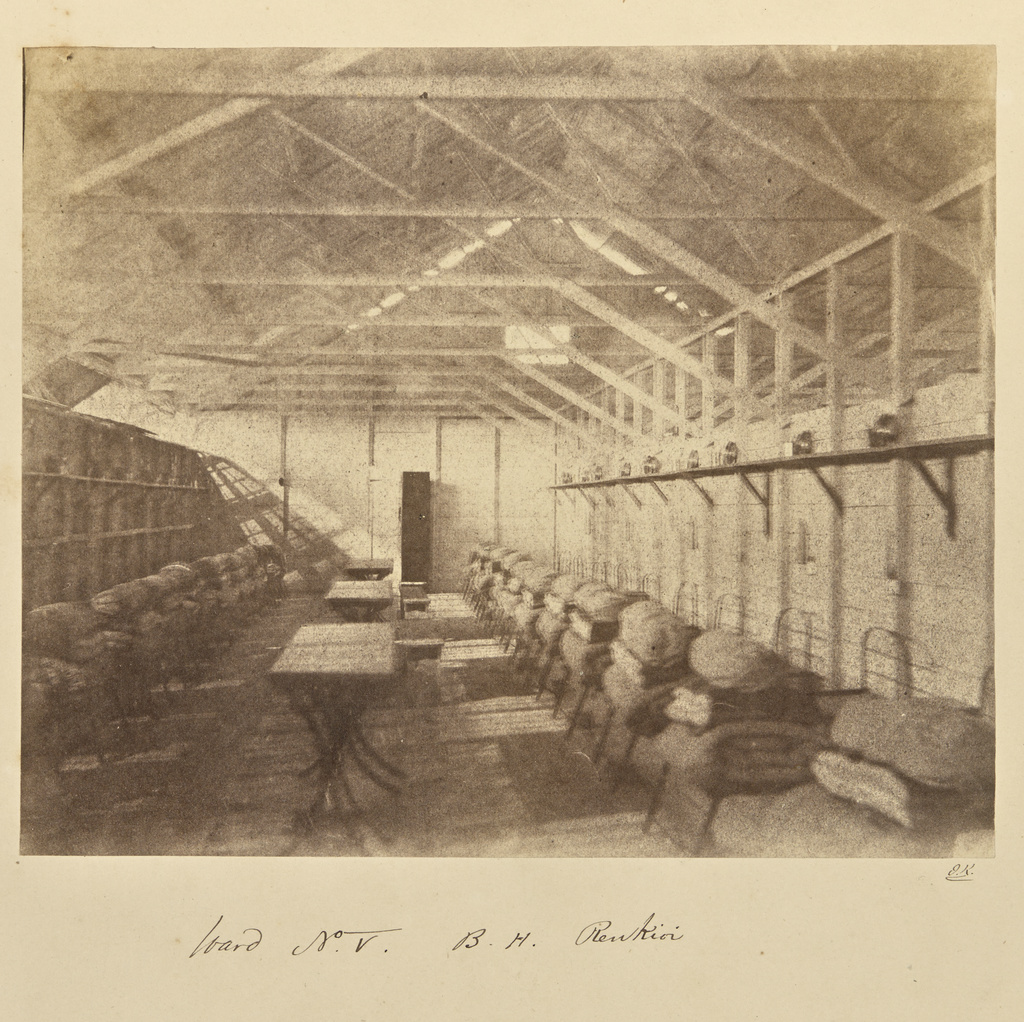

John Kirk, photographer (Scottish, 1832 – 1922), Ward N° V B. H. Renkioi, Scottish, 1855 – 1856, Albumen silver print from a paper negative, 15.5 × 18.8 cm (6 1/8 × 7 3/8 in.), 84.XA.619.19. Courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

For safety, a kitchen made of iron was slightly detached from the wooden buildings and fully fitted to be capable of cooking for up to 1,000 patients. A similar building of iron was fitted with all the latest machinery used in baths and washhouses in London for washing and drying, in the minimum of space and with the least amount of labour.

Each set of buildings was sent with pumping apparatus, a small general reservoir, and a length of main with all its branches to supply water to every detached building. The construction allowed the pieces to be pushed together without the need for soldering or cement. A system of drains was also supplied, formed of wooden trunks painted inside with tar so that when joined together formed a perfect system of drainage from every building to a safe distance from the general hospital. There was no leakage in 15 months of use and it was considered that they would have lasted at least two to three years.

Portable baths were designed so that less mobile patients could be lifted by frame or sack to a bath by the bed.

The construction of each building had been studied with very great care so as to use the minimum amount of material, the least possible amount of work to construct and the ability to arrange all the parts in separate packages each capable of being carried by two men. The units could also therefore be loaded onto different vessels so that if there was an accident or mistake not all was lost. The engineer on site to supervise the building was Mr Brunton.

In all 23 steamers and sailing vessels were dispatched containing 11,500 tons of materials and stores. The first arrived on 7th May 1855 and the last on 5th December. The hospital was ready to receive 300 patients on 12th July 1855 and in total treated 1,408 soldiers and civilians.

John Kirk, photographer (Scottish, 1832 – 1922), Engineers’ Hut, B.H. Renkioi, Scottish, August 1855, Albumen silver print, 10.7 × 18.5 cm (4 3/16 × 7 5/16 in.), 84.XA.619.1. Courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Written by Gillian Howard

To donate and kindly give vital help towards the Museum’s running costs as a result of the Covid-19 Crisis please click here: