An appearance from a famous person is always a great way to advertise and bring excitement to any project or idea. This post looks into how members of royal families – the celebrities of the 19th century – were not only interested in the Thames Tunnel but also how the press reported on those visits and how the symbiotic relationship between media interest, royalty and good old capitalism is not exclusive to the current days of social media.

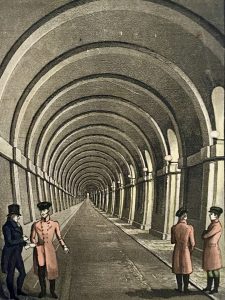

The Thames Tunnel (built between 1825-1843), an engineering marvel of the 1800s, something Marc Brunel called it the “most difficult task imaginable”, was a bold idea and one difficult to sell: an underwater passage way under the river Thames to facilitate the transport of people and goods from one shore to the other, something no one had successfully managed before, in London or anywhere else.[1]

A View of The Western Archway of the Thames Tunnel, Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2024.10

Such an achievement was covered in detail by newspapers (in Britain and elsewhere) to a great extent. The publics interest was high regarding the tunnel and its construction, and the press was how people would keep informed on what was happening in the world.

One can even say that it all came together in the press: the Tunnel was interesting enough to be reported on and people wanted to learn about it, newspapers were an important source of information and also a way for someone to build – or maintain – public support and a favourable public image.

And this is where common interests meet: the newspapers need to sell and inform a growing public alongside the possibility of attaching yourself to a monumental event – in this case, the first tunnel under a navigable river – and in the first half of the 1800s, no one needed a public relations turn around more than the royal family.

After decades of scandals regarding money squandering and the private lives of King George’s children, newspapers knew that anything related to royalty was guaranteed to attract interest. Be it due to history, position, our awareness of protocol or curiosity, a visit by someone with a His/Her Royal Highness title attached to their name has always been what we’d now call a great (and welcome) public relations boost.

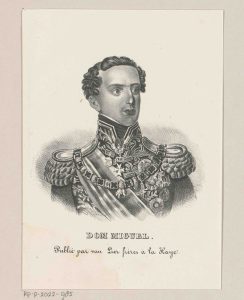

Dom Miguel, Regent and King of Portugal, 1833-1834, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-2022-985

On January 8th 1828, while the tunnelling was under way, The Times reported that Dom Miguel of Portugal (then Regent of the Kingdom) visited the tunnel construction site while in England to meet with Portuguese business men and speak to members of the British government. His Royal Highness was hosted and received by Marc Brunel himself. Anxious about the descent, the Prince Regent asked about the specificities of the project and then proceeded to go down the shaft, where he toasted the health of Portugal, Britain and his august host King George IV. [2]

Then on February 2, 1842, Frederick William IV, King of Prussia visited London and went down to the Tunnel as part of his itinerary. His immense curiosity was quite common for the time, as it was in fashion then to visit, inspect or see the works being done at the tunnel – at this time almost complete. His Majesty went down and praised the whole endeavour – as written by The Observer – and was quoted as asking Sir Marc Brunel “how much water lies above us?”.[3]

Woven portrait of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their eldest son, Prince Albert Edward, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Washington, D.C., 1995-50-369

A few months after the tunnel was inaugurated, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert went on an impromptu visit to the tunnel in July 1843 to great cheers – but the monarch was disappointed to learn that Marc Brunel was not present. Her presence caused great commotion and “God Save the Queen” was sung by a multitude of people.

The Queen’s presence was also a major business opportunity, like the stall keeper that laid down a handkerchief for the monarch to step on and proceeded to sell that one (and many others) simply for its brief association to the royal feet. Another, a Mr. Langston, saw such visit as a chance to present the Queen with a pincushion made of vegetable ivory and was invited to Buckingham Palace as a result, as mentioned by the Times on September 1843.[4]

Particularly after 1837, the year of Queen Victoria’s ascension to the throne, the Monarchy went through a “rebranding”. So association with the new monarch and her family was a welcome thing for a project which had struggles so much in the past – and also to those around it, much like the stall keepers mentioned and the newspapers reporting on the coming and goings of the royal family.

One final royal visitor worthy of praise and note was when The Times informed that Grand Duke Michael of Russia visited the tunnel on October 1843 and was escorted around by one of the engineers, Thomas Page, showing great interest while receiving a gold medal of Marc Brunel as a token before leaving.[5]

Daily papers would report on the fashionable and rich coming to parts of the city they would not normally visit, making a connection between engineer greatness and human curious nature. With the Tunnel, the East End became the sight of what many considered the most impressive engineering project in the world.

And if a Russian Grand Duke and the Queen herself would venture out to the then wild East End, the dangerous and poor part of London, why wouldn’t you?

To find out more about the Thames Tunnel, visit the Brunel Museum – book tickets here!

This post was written by Pedro Briggs and developed as part of an internship program at the Brunel Museum during the Winter/Spring of 2025. The internship and blog formed part of his assessment for his MA in History at Queen Mary University of London, and were part of studies into public history and the work of the heritage sector.

References

[1] Marc Isambard Brunel to Jacques-Charles Allard, 6 May 1840, Archives Départementales de l’Eure, Évreux, côte 3F/488 (‘l’Entreprise le plus penible [sic] que l’on puisse citer’).

[2] “Don Miguel”, The Times, 9 Jan. 1828, p. 2.

[3] “The King of Prussia”, The Observer, 30 Jan. 1842, p. 1.

[4] “Present to Her Majesty” The Times, 14 Sep. 1843, p. 4.

[5] “The Grand Duke Michael of Russia”, The Times, 9 Oct. 1843, p. 4.