In celebration of LGBTQ+ History Month, Jack Hayes shares new information about the visits of pioneering queer figure Anne Lister (1791-1840) to the Thames Tunnel.

From proposing the Tunnel as a venue for an ‘ungentlemanned’ date with a woman, to considering Brunel’s innovative tunnelling methods in relation to mines on her family’s estate, Lister’s visits to the Tunnel were as personally exciting as they were influential in developing her knowledge of scientific innovation.

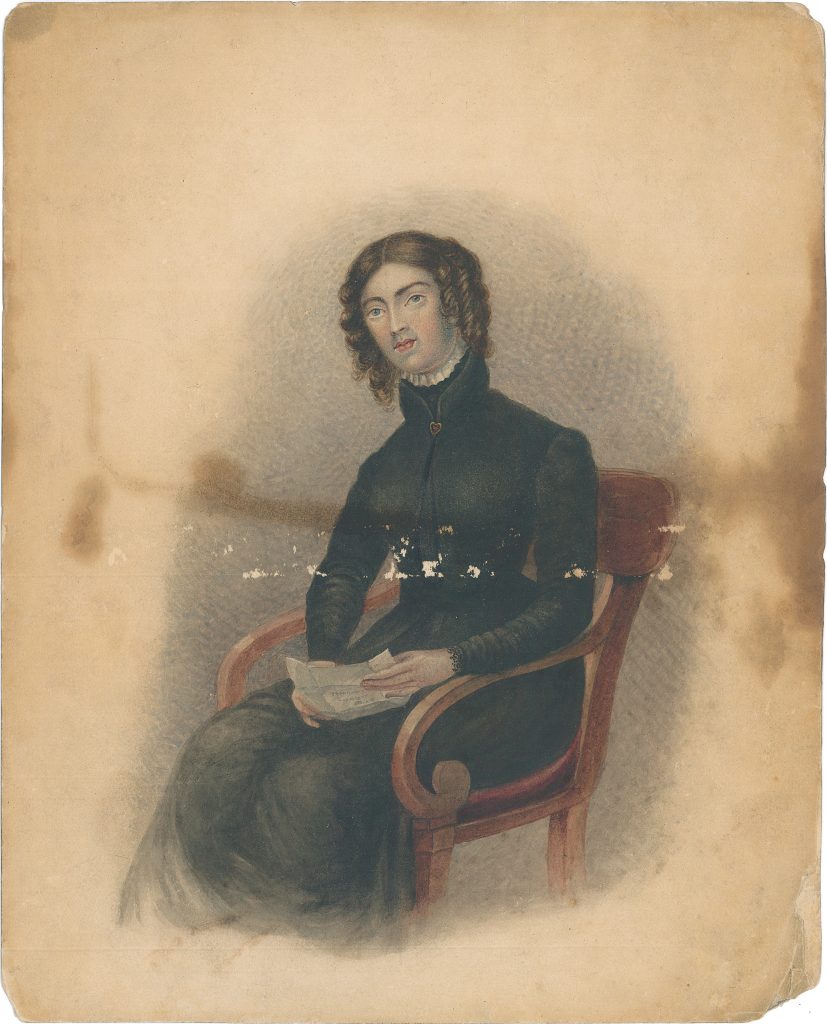

Portrait of Anne Lister, West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale, SH:2/M/19/1/59

In celebration of LGBTQ+ History Month, we’re excited to share new information about the visits to the Thames Tunnel, on the site of which the Brunel Museum is now located, of pioneering queer figure Anne Lister (1791-1840).

Lister – sometimes better known under the pseudonym Gentleman Jack, and recognizable to many from the BBC television series (2019-22) in which she was played by Suranne Jones – is considered by some the first modern lesbian.

Born in West Yorkshire into a wealthy landowning family, Lister, who largely dressed in ‘male’ clothing, defied gender-norms and the expectations placed on her throughout her life.[1] In 1834 Lister took sacrament at a church in York with Ann Walker (1803-54). The couple then considered themselves officially married, and went abroad on honeymoon. Many have recognized this as the first same-sex marriage in Britain, and the church has carried a plaque commemorating the marriage since 2018. This was the first ‘rainbow plaque’ installed in the UK.[2]

Lister left a series of diaries, some written in code, that provide detailed discussions of her life and her relationships with women. These are now held by the West Yorkshire Archive Service, and are available online thanks to the Anne Lister Diary Transcription Project (find out more about how to read them here). They are a rare first-hand account of queer relationships which largely remained hidden, and are often now only visible to historians in less happy documents such as trial records.

Lister’s family owned coal mines, and she was greatly interested in their operation. No surprise, then, that innovations in tunnelling were also of interest to her, and especially the Thames Tunnel, the world’s first tunnel beneath a navigable river built 1825-43. Lister’s diaries first show news of the Thames Tunnel spreading across the country via scientific journals and word of mouth. Later, we see her thinking through how methods pioneered by Marc Brunel on the Thames Tunnel could be employed at coal mines under her control.

In 1831-33, Lister travelled to London and visited the Tunnel itself twice. On at least one of these occasions, Lister’s diary implies that she proposed the Thames Tunnel as a venue for a date, when she proposed that a woman with whom she had had a long flirtation accompany her to the Tunnel ‘ungentlemanned’!

Anne Lister and Marc Brunel

Lister’s earliest reference to Marc Brunel refers not to the Thames Tunnel, but to a description of his patent for producing metallic foil which Lister read on 4 May 1819 after it appeared in Ackerman’s Repository of Arts.[3] The patent for a process to produce shiny foil intended to decorate furniture was unusual in the context of Brunel’s inventions, and perhaps also too in the context of Lister’s interests. However, already we see Lister here reading widely to keep abreast of scientific innovations and new technology.

In 1818, the same year Brunel patented his metallic foil, he had also submitted a patent for a method of tunnelling using a tunnelling shield. A few years later, Brunel then published this scheme for tunnelling into soft ground. Lister read the announcement of the plan on 1 May 1824 in the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, skimming Brunel’s piece entitled ‘On a New Plan of Tunnelling, being Calculated for Opening a Roadway under the Thames’.[4]

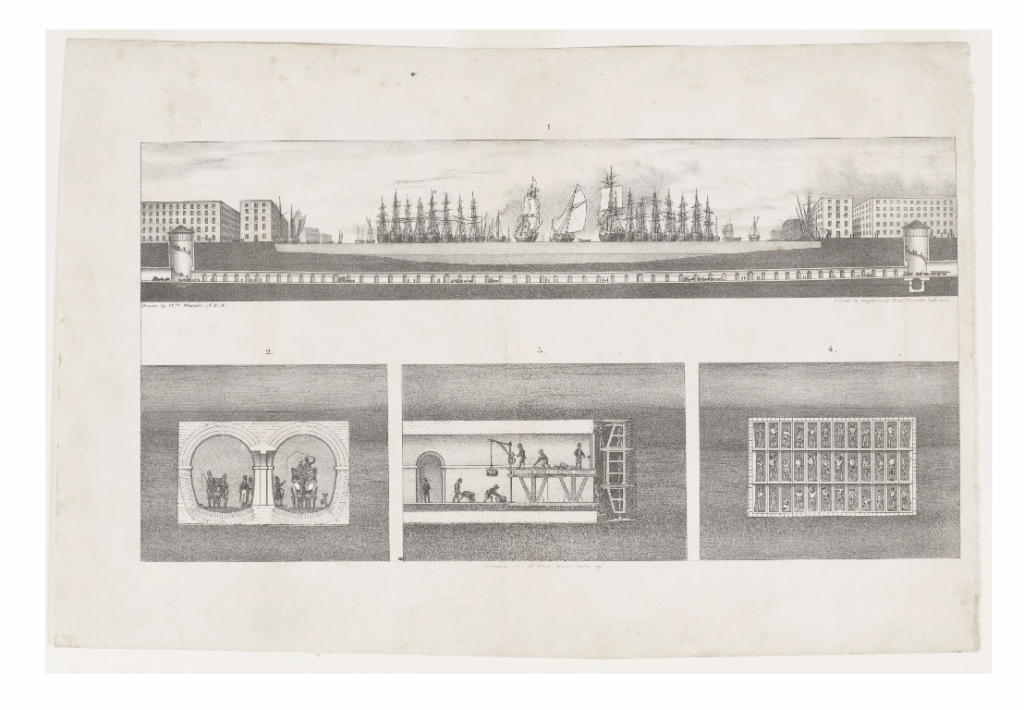

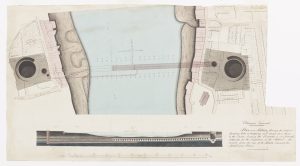

Composite sheet of prints depicting the construction of the Thames Tunnel, about 1825? Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.28(b)

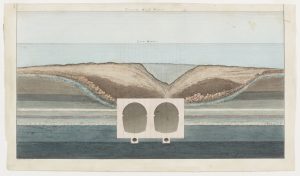

Watercolour showing displaced ground following flooding, and the Tunnel below, about June 1827. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.16

Brunel’s plan as published in the Journal read by Lister included a composite plate of engravings showing various aspects of the scheme: they are close in style to a number of engravings in the Brunel Museum’s collection, which were intended to explain and demonstrate the project and its innovations to a lay audience.

On 16 February 1825, work began on the Thames Tunnel. Lister, who already knew about the project’s method, records hearing information and updates about progress made. In March 1828, Mr. Webb, owner of a hotel at which Lister stayed when in London, had attempted to visit the Tunnel. He had been stopped by water ingress and was not hopeful for chances of completion, as Lister reported in her diary:

— Had Mr. Webb upstairs — meant to have gone to see the tunnel under the Thames at Rotherhithe, but nothing to see — full of water again — he thinks it will be given up —[5]

The same day, Lister noted elsewhere that the whole project might be abandoned.[6] Two months earlier, severe flooding had killed six men working at the Tunnel, and almost killed Marc Brunel’s son Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-59). Anne Lister was therefore not the only person who was sceptical it would ever be finished!

Anne Lister’s Visits to the Thames Tunnel, 1831-33

While not abandoned, construction of the Thames Tunnel was put on pause pending changes to the method and a new cash injection. However, once damage caused by the flooding had been dealt with, the Thames Tunnel Company reopened the works for visitors. They provided a crucial source of income, and many were still fascinated by this construction site as a tourist attraction.

Lister, it seems, only decided to visit the Tunnel after this well-documented fatal flooding. While there is perhaps something macabre in choosing to visit after this event, the accident clearly increased public awareness of, and fascination with, the Tunnel works. In the late 1820s, it was decided to place a large mirror at the end of the uncompleted Tunnel, to give a sense of what it might look like when extended. The effect was surely dramatic, and itself proved a draw.

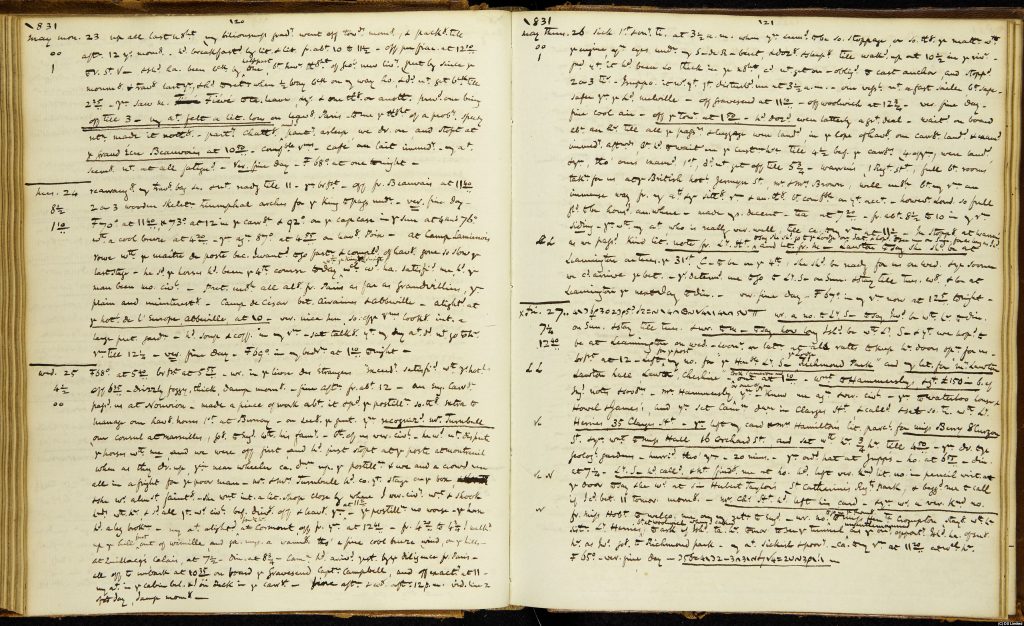

Anne Lister’s diary entry inviting Henrietta Compton to go ‘ungentlemanned’ to the Thames Tunnel, Friday 27 May 1831. West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/14/006

So it was that on Friday 27 May 1831, Anne Lister wrote to Henrietta Crompton ‘to ask if I should take her tomorrow to see the tunnel ungentlemanned’.[7] Crompton had known Lister for many years; the Crompton family lived in York, and Lister was a frequent visitor at their home. Crompton never married, and Lister appears to have been quite taken by her.

Unfortunately for Lister, Henrietta Crompton refused this invitation to go ‘ungentlemanned’ to a muddy construction site, and suggested instead they meet on Saturday evening.[8] Undeterred Lister got up the next day and went to the Tunnel by herself:

…then to Rotherhithe to the tunnel at 2 55/.. — in (to the end) and out again in 10 minutes — […] the tunnel an amazing work — descended 126? steps down the shaft into it — the tunnel divided into 2 arched ways, 1 for going 1 for return carriages — good foot ways on each side — well lighted up with gas — hope to get money to complete it in about 2 years — will take £200,000 —[9]

Two years later, Lister was more successful in convincing women to visit the Tunnel with her. On 15 July 1833, she spent the day with a group of women driving around the city. They first visited the museum of the East India Company, where Lister saw, amongst other things, the silver howdah of Durjan Sal which had been looted at the 1826 Seige of Bharatpur and had arrived in London in 1828.[10] They then went to St. Paul’s Cathedral, after which they had no plans.

Someone – was it perhaps Lister? – suggested they go see the Tunnel:

…no plan arranged — hesitation what to do — drove off to the tunnel — then saw close by Brunel’s 2 semi-arches shewing [sic] how an arch might be built without centres, — on the principle of connecting the brick-work by iron laths (about the width and thickness of barrel-hoop) the whole length of each course of bricks the iron not seen because cut off 1/2 brick’s breadth from the outside walling of the arch —[11]

Lister’s second visit in 1833 coincided with a series of experiments by Brunel to produce arches of different types.[12] Lister’s diary clearly shows her examining these arches with interest, pondering at their construction perhaps more than many visitors could be expected to do. While the group of women travelling around various tourists sites in London cannot have been very unusual, Lister devotes as much space in her diary to the construction of the Tunnel as to the India Museum. St Paul’s, now by far the best known of the sites Lister visited in 1833, is noted only in passing.

Apparently, as far as Lister was concerned, the Thames Tunnel, and the methods employed on site, were just as exciting as grand imperial museums; and even more so than the baroque architecture of Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s.

The Thames Tunnel’s Influence on Lister’s Later Projects

Lithograph map showing progress of the half-completed Thames Tunnel, with Marc Brunel’s annotations. Mid-1830s. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.26

Lister did not return to the Thames Tunnel after 1833. In the meantime, she had met Ann Walker, writing of her in her diary in 1832:

She falls into my views of things admirably. I believe I shall succeed with her – if I do, I will really try to make her happy – […] She will look up to me and soon feel attached and I, after all my turmoils, shall be steady and, if God so wills it, happy […] How strange the fate of things! If after all, my companion for life should be Miss Walker –[13]

A year later, Anne Lister married Ann Walker in York, and the couple began to live together at Shibden Hall, Lister’s family seat in Halifax.

In the mid-1830s, Lister focussed largely on alterations to Shibden Hall, and on various works related to coal mines on the estate she had recently inherited. Visits to the Tunnel had clearly inspired the newly-married Lister, and given her useful information about potential solutions to problems faced in mining and construction projects. She reports in her diary one meeting held in 1835 to discuss constructing a driftway in a mine:

I said better to make a culvert […] walled and arched — he said it would be very difficult to do — perhaps might be done by wood props to keep up the stuff, till arch by arch bit by bit, was done — Yes! Said I as they did the Thames Tunnel —[14]

Lister’s attentiveness, in print and in person, to the innovative tunnelling methods put into practice by Brunel at Rotherhithe had informed her view of what could be possible in her own mining operations. Though the Thames Tunnel had been beset by problems and difficulties, in this diary entry Lister is confident similar method could be employed in Yorkshire.

Away from London, Lister clearly kept up with news of progress on the Tunnel, likely through reading the many newspaper reports which detailed news of the construction. In November 1839, she recorded a far more optimistic note about how work was going:

Thames tunnel now reaches low water mark ⸫ [therefore] no fear of another irruption — Length of tunnel now = 920 feet being little short of 3/4 of the whole distance there being about 380 feet more to complete the entire length — the tunnel is expected to be opened for passengers towards the latter end of next year —[15]

The Tunnel was not completed the next year, and only opened to the public on 25 March 1843. In the meantime, Anne Lister had gone travelling where, on 22 September 1840, she died at the age of 49 in Koutais in what is now Georgia. We can only imagine what she would have made of the completed Tunnel.

Her wife, Ann Walker, remained at Shibden Hall where the pair had lived together for many years: she never remarried, and eventually died in 1854. Far less well known than Anne Lister, Ann Walker was the subject of the In Search of Ann Walker project, which in 2020 led to the rediscovery of her 1834 diary, allowing a fuller understanding of her marriage to Anne Lister to be constructed.

To find out more about Anne Lister, see the sites provided by Calderdale Museums and the blogs hosted by West Yorkshire Archive Service. You can also visit Lister’s home, Shibden Hall.

If you’re interested in more LGBTQ+ Thames Tunnel history, take a look at the story of William Burt and John Reagan, Thames Tunnel construction workers who were caught up in a criminal trial in May 1827.

Want to walk in Anne Lister’s footsteps?

Book tickets to visit the Brunel Museum, and the Tunnel Shaft Anne Lister descended in 1831-33.

Bibliography

[1] On Lister, see esp. Decoding Anne Lister, ed. by Caroline Gonda and Chris Roulston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), with bibliography.

[2] See Kit Heyam, ‘Rainbow Plaques: Making Queer History Visible’, Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain, 11 August 2020, online via: https://www.sahgb.org.uk/features/rainbow-plaques-making-queer-history-visible. On Lister and changes to the wording of the plaque in 2019, see also Heyam, Before We Were Trans (London: Basic Books, 2022), 84-90.

[3] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/3/0003, undated list of books read, 1819, ‘[May] 4 Brunel’s newly discovered metallic paper’.

[4] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/7/0129, 1 May 1824: ‘Took the last no. [number] (20) Edinburgh Philosophical Journal for April which though I got it on the 6th I have never yet had time to look at — Skimmed over from page 276. to 317. vide Brunel’s plan of tunnelling under the Thames, M. Seguin’s paper on the effects of heat and motion very curious.’

[5] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/10/0142, 21 March 1828.

[6] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/10/0175, 21 March 1828: ‘Thames tunnel will be abandoned?’.

[7] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/14/0064, 27 May 1831.

[8] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/14/0065, 28 May 1831: ‘I had sent my note (written last night) to ‘Miss Henrietta Crompton, 35 Clarges Street’ and had had an answer that she could not possibly go with me to see the tunnel, but they should be glad to see me in the evening —’.

[9] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/14/0065, 28 May 1831.

[10] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/16/0081, 15 July 1833. On the howdah and the India Museum, see Arthur MacGregor, The India Museum Revisited (London: UCL Press, 2023), pp. 7 and 26.

[11] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/16/0081, 15 July 1833.

[12] On these experiments, see e.g. Richard Beamish, Memoir of the Life of Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1862), pp. 284-6; Harold Bagust, The Greater Genius? A Biography of Marc Isambard Brunel (Shepperton: Ian Allen, 2006), p. 85.

[13] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/15, 27 September 1832.

[14] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/17/0178, 11 March 1835. On Lister’s renovation and construction projects in this period, see Angela Clare, ‘Anne Lister’s Home’, in Gonda and Roulston, eds, Decoding Anne Lister, pp. 151-67 (pp. 156-60).

[15] West Yorkshire Archive Service Calderdale, SH:7/ML/E/23/0129, undated, November 1839. See also SH:7/ML/E/23/0128, undated, mid-November 1839: ‘the shield of the Thames Tunnel is now within 15 feet of the Middlesex side […] 4 feet length of tunnel lately done per week —’.