![Text from an old book - reads: AN ACT FOR Making and maintaining a Tunnel under the River Thames, from some Place in the Parish of Saint John of Wapping, in the County of Middlesex, to the Opposite Shore of the said River, in the Parish of Saint Mary Rotherhithe, in the County of Surrey, with sufficient Approaches thereto. [ROYAL AsSENT, 24th June 1824.]](https://thebrunelmuseum.com/app/uploads/2023/10/investor002-814x1024.jpg)

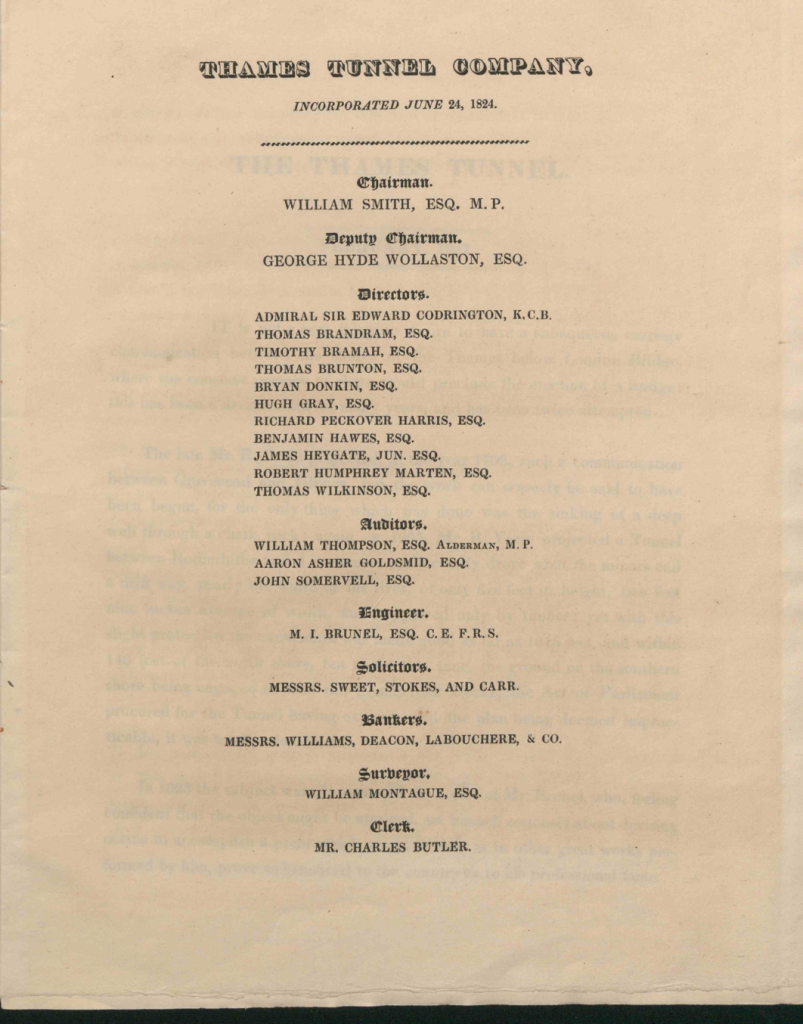

The Act goes on to note, the proprietors (investors) were –

willing and desirous, at their own Expense, to make and maintain the said Tunnel.

Some notable Thames Tunnel investors …

The Bramahs

Timothy, Francis & Edward Bramah were all sons of Joseph Bramah (1748-1814) a pre-eminent inventor and engineer famous for his locks. By 1821, Timothy, Francis and Edward had all become partners in the Bramah engineering business. Between them they owned 30 shares in the Thames Tunnel Company and Timothy Bramah was also elected to the Court of Directors of the Thames Tunnel Company. However, in 1827 there appears to have been an altercation between Timothy and the young Isambard Kingdom Brunel. This took place in Rotherhithe during a meeting of company’s Committee of Works, this almost certainly took place in The Spread Eagle pub (today known as The Mayflower). Isambard describes Timothy Bramah as “the Pimlico engineer!… too ignorant to speak to good purpose he has drilled the other to his own mischievous one”. Whilst there were several issues raised, a key and what would seem a justifiable concern of Timothy Bramah, was the quality and efficacy of the borings taken to determine the nature of the strata under the river.

Today, Bramah is London’s oldest security company, established in 1784 at 124 Piccadilly, the company is still Marylebone’s and Fitzrovia’s foremost Locksmith and Burglar Alarm installer. Indeed, in the Summer of 2023, the Managing Director, Jeremy Bramah, visited the Museum.

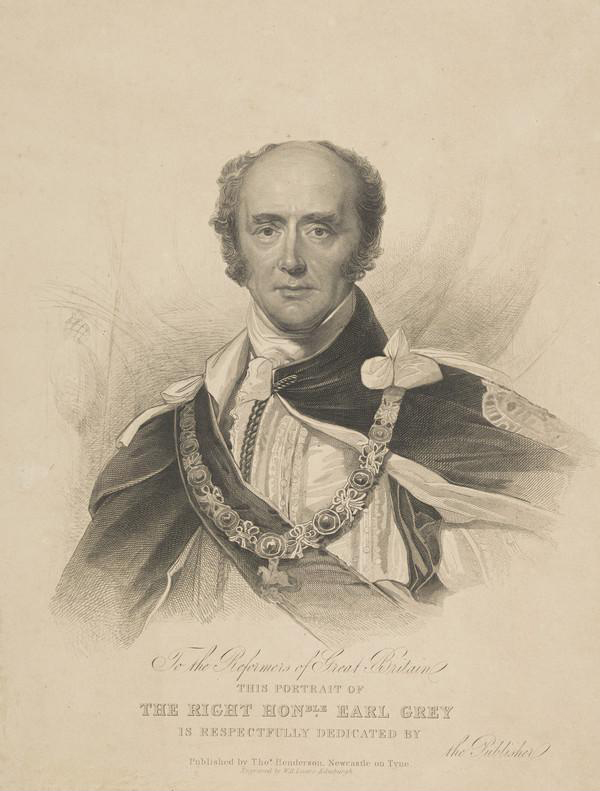

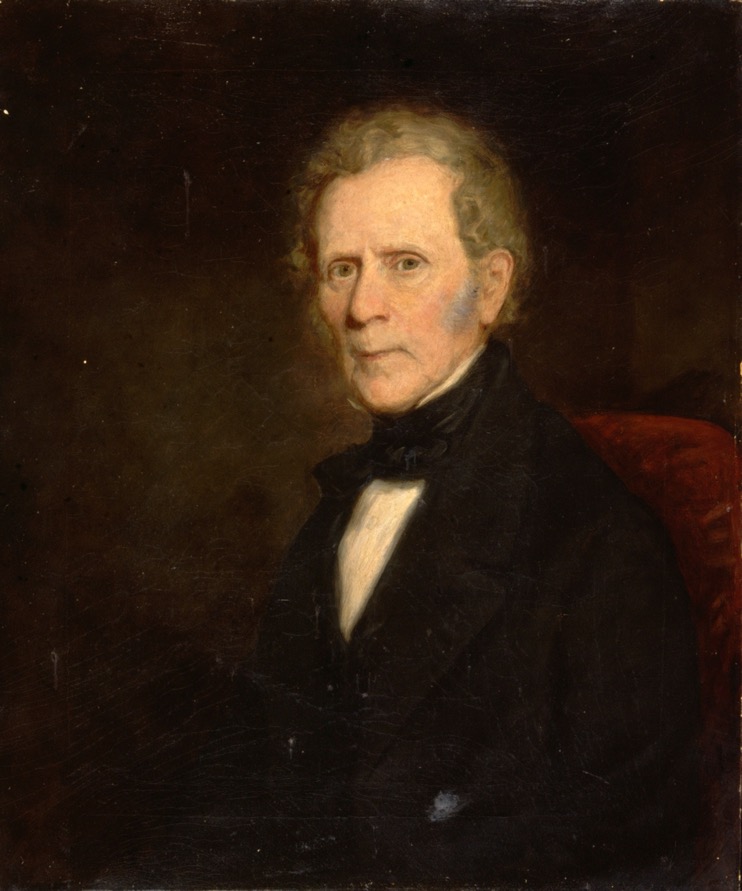

Prime Minister, 1830-1834

https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/104599/charles-grey-2nd-earl-grey-1764-1845-prime-minister

The Twinings

Richard, George and John Aldred Twining were all members of the world-famous Twinings tea dynasty that dates back to the early 18th century. The number of Thames Tunnel Company shares purchased by the three brothers is unclear.

Richard Twining II (1772–1857), took over the Twinings business in 1818. He continued to offer bespoke tea blends at the company’s Golden Lyon shop on The Strand. A notable customer of Twinings was the then Prime Minister Charles Grey. It was one of Grey’s envoys in China that saved the life of a Chinese mandarin. As a thank you, tea was given to the envoy together with its recipe, the latter normally a well-guarded secret. The envoy took the gift back to England and presented it to Prime Minister Grey. This new tea became so popular with Grey, his colleagues and friends, that in 1831 Grey asked Twinings to recreate it. The blend became known as Earl Grey, named after Prime Minister Charles Grey, the 2nd Earl Grey.

When work began on the Thames Tunnel in 1825, John Aldred Twining also founded Twinings Bank, his brother George becoming a partner in the bank. The Twinings Bank merged with Lloyds Bank in 1892.

William Smith, MP for Norwich and Chair of the Thames Tunnel Company, was one of the first to campaign for the abolition of the slave trade back in 1787, and became a vocal advocate for the cause, and would go onto support William Wilberforce. In 1823 with Zachary Macaulay he helped found the London Society for the Abolition of Slavery in our Colonies, thereby launching the next phase of the campaign to eradicate slavery.

Sir Alexander Crichton

Not all those involved with the Thames Tunnel company fought for the abolition of the slave trade, and many directly benefited from it.

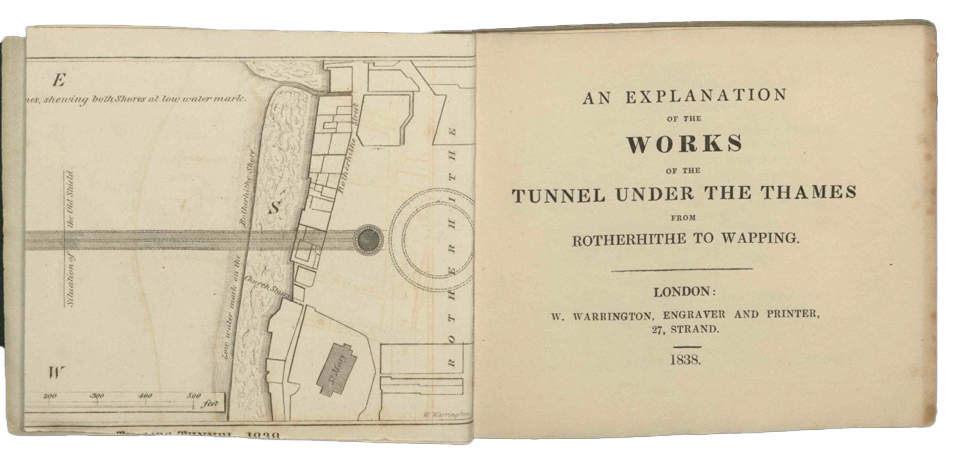

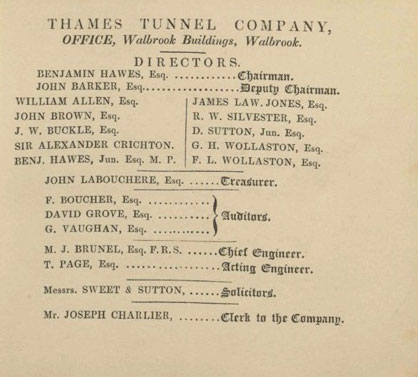

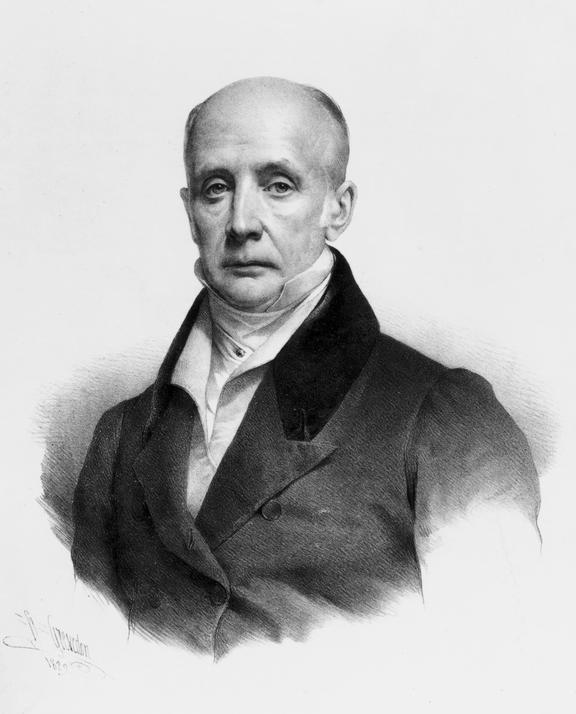

Alexander Crichton (1763-1856) was not listed as a shareholder or director in the original Thames Tunnel Act of 1824. However, by 1838 he is listed as a director of The Thames Tunnel Company – how, when or why Crichton became a director is unclear.

Crichton was physician to the Imperial Russian Court and Tsar Alexander I of Russia. He was knighted by King Frederic William III of Prussia. After returning to the UK, he was also knighted by King George IV in 1821. Crichton was a pre-eminent physician and a pioneer of diagnosing ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and CDS (cognitive disengagement syndrome). Crichton would seem to be an unlikely investor in the Thames Tunnel project.

However, after The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, compensation was awarded to the owners of enslaved people. Crichton was a beneficiary of this compensation circa 1836. The sum of £697 6s 8d was paid to the trustees of his marriage settlement. It should be noted that Crichton did not buy the “1/6th part ownership” of the 240 enslaved people on the Morant Estate in Surrey, Jamaica, he acquired these enslaved people through his wife’s marriage dowry. Whether Crichton used some of the £697 compensation to invest in The Thames Tunnel is far from clear. He may well have been an investor in The Thames Tunnel Company prior to receiving this compensation.

Bryan Donkin

Not widely known, Bryan Donkin is a significant figure of The Industrial Revolution, the history of engineering and mass production. He was somewhat of an engineering polymath, amongst his many achievements Donkin built the world’s first practical paper-making machine (before this all paper was made by hand). Invented and manufactured the steel pen nib, he was also the first to successfully preserve food by canning. Born in 1768 in Northeast England, Donkin set up his engineering business near Grange Road, Bermondsey, London in 1803. Nine years later he also opened the world’s first canning factory in the same area.

Donkin was a friend and advisor to the likes of Thomas Telford, Charles Babbage, Marc Brunel and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. As a founding investor and Director of the Thames Tunnel Company he owned 20 shares. Indeed, it would seem that Donkin was the only Director of the Company, who Marc Brunel respected for his professional engineering knowledge and judgment.

Donkin’s engineering factory was about a fifteen-minute walk southeast of the Brunel Museum and his company was Marc Brunel’s first choice for the manufacture of the tunnelling shield. However, as a shareholder and Director, Donkin was forbidden from benefiting from Thames Tunnel Company business. In the event, most of the Thames Tunnel machinery was supplied by Henry Maudslay.

Bryan Donkin retired from the Court of Directors when the Thames Tunnel Company was refinanced by the Treasury in December 1834. Donkin died at home in the nearby New Kent Road in 1855 and was buried in a monumental family vault in Nunhead Cemetery.

The Brunel Museum tells the story of the Thames Tunnel, and continues the tradition of welcoming visitors to the Museum. What will you make of it?

We’re planning to include a lot more stories of the people who visited the Thames Tunnel in our Brunel Museum Reinvented project. Donate today to help us tell those stories.