The Thames Tunnel was immensely popular as a tourist attraction when it first opened on 25 March 1843 with one million visitors in its first ten weeks. – But people also visited before it was even open.

Let’s take a look at some of those people:

Fanny Kemble

Fanny Kemble described a visit to the Thames Tunnel in 1827 as ‘an unusual favour which of course delighted us all’. She writes,

“So we left our broad, smooth path of light, and got into dark passages, where we stumbled among coils of ropes and heaps of pipes and piles of planks, and where ground springs were welling up and flowing about in every direction, all which was very strange.”

She describes the tunneling shield as,

“an iron frame has been constructed—a sort of cage, divided into many compartments, in each of which a man with his lantern and his tools is placed—and as they clear the earth away this iron frame is moved onward and advances into new ground. All this was wonderful and curious beyond measure”

Born in 1809, Fanny Kemble was a British actress who made her theatrical debut in October 1829 in Covent Garden. She later married a plantation owner and when she saw first hand the conditions of the enslaved people, she became a vocal critic of the slave trade.

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

One of the greatest composers of the nineteenth century visited the Thames Tunnel at least three times. Mendelssohn’s first visit was on 13 June 1829, whilst the Tunnel was still being constructed. He returned again in 1833 with his father. In June 1842, Mendelssohn again visited the Tunnel, this time with his wife Cécile. Surprisingly, there is little record of what Mendelssohn made of the Tunnel – but he must have found it fascinating if he came back so often!

[Briefe aus den Jahren 1830 bis 1847 von Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, ed. by Paul Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Carl Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. Vol. 2 (Leipzig: Hermann Mendelssohn, 1863), p. 212; Larry Todd, Mendelssohn: A Life in Music. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 209, 282]

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert

A few months after opening, the Thames Tunnel was visited by no less than Queen Victoria and Price Albert, who arrived by royal barge. One of the stall keepers in the tunnel, seeing the Queen approach, proceeded to tear down the wholestock of his silk pocket-handkerchiefs in order to lay on the ground for her to walk over. He was clearly a shrewd businessman, for the hankies were sold during the rest of that day form half-a-guinea each.

Quite a few visitors who had been unceremoniously locked into the tunnel when the Queen arrived, huddled together on one of the landings and then proceeded to sing ‘God Save the Queen’ as the royal party re-ascended the staircase. The magazine declared that the effect of the national anthem ‘sung in different times, different keys, and almost different tunes, was quite electrical’. The Scotsman was slightly more polite in its report, declaring that the anthem was sung ‘more loyally than musically’. The Queen expressed her regret at Mr Brunel not being present for her visit and then left the site amid prolonged cheers.

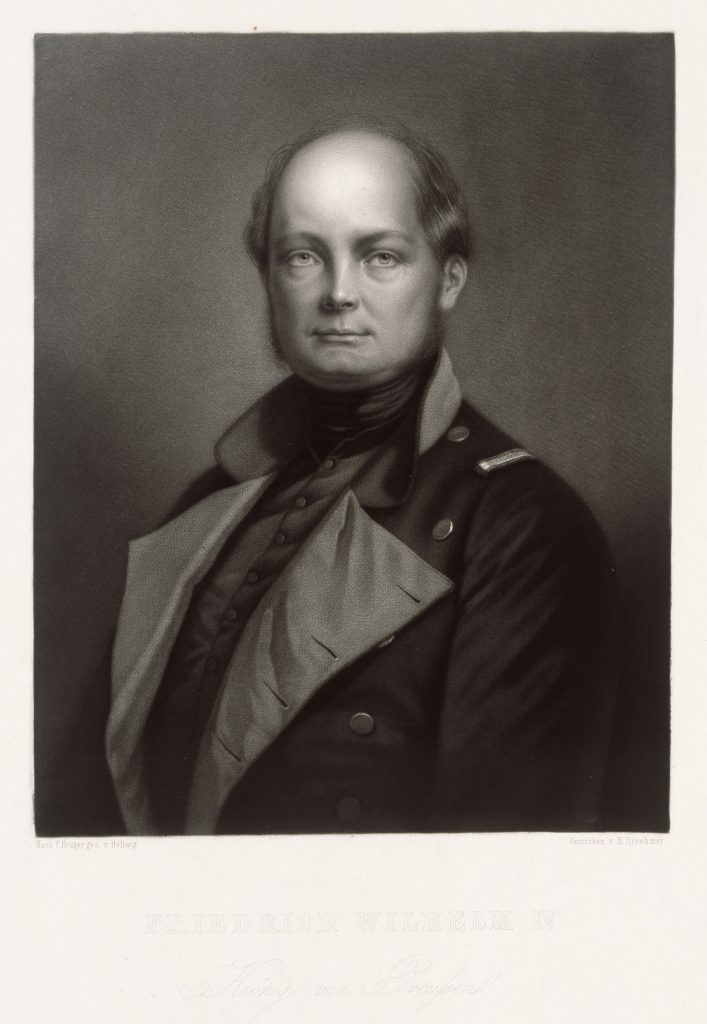

King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia

On February 2nd 1842, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia visited the Thames Tunnel, meeting with Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his brother-in-law Benjamin Hawes.

One German newspaper gave an account of the royal visit as follows:

‘At the entrance to the Tunnel, His Majesty received the engineer, Sir Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the chairman of the Board, Mr. Benjamin Hawes, and, though it was early in the morning, a considerable number of members of the nobility and gentry. When they reached the bottom of the stairs, where one can see down the Tunnel’s two corridors lit with gas lamps, the King exclaimed with surprise: “How beautiful this is!”. Shaking the engineer’s hand again, he added in English: “Your work surpasses everything I have previously heard. I thought the reports exaggerated, but now I see the printed descriptions fall short of reality. How much water lies above us, Sir Isambard?”.’

[Augsburger Tagblatt. Dreizehnter Jahrgang (Augsburg: G. Geiger, 1848), p.178]

Motilal Singh

In 1850, Motilal Singh, a Nepalese soldier persuaded to move to Britain by an English Captain, visited the Tunnel.

‘…A long distance then we went, through a thickly- populated town, smelling of tan, till we came again to the river-side, where, descending by winding stairs till we lost the light of day, we entered the place called ” Tunnel.” The English are so fond of variety that, being tired of going over the Thames on bridges, they resolved to pass under it through holes. For this reason they lured a clever French- man to construct them a road under the water. It cost them many millions of their money, and now that it is finished they make no use of it for the purpose for which it was intended. There are many other things in London that, in this respect, resemble the ” Tunnel.”

Motilal Singh is considered to be the first Nepalese individual to have visited London.

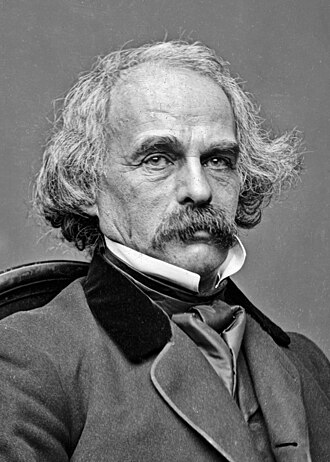

Nathaniel Hawthorne

By the 1850s, the Thames Tunnel had developed a reputation as a place where pickpockets operated, and earnt the nickname the ‘Hades Hotel’. Visiting in 1855, the American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote that the Tunnel:

…consisted of an arched corridor of apparently interminable length, gloomily lighted with jets of gas at regular intervals […]. There seem to be people who spend their lives here, and who probably blink like owls, when, once or twice a year, perhaps, they happen to climb into the sunshine. All along the corridor […] we see stalls or shops in little alcoves, kept principally by women […] they assail you with hungry entreaties to buy some of their merchandise. […] So far as any present use is concerned, the tunnel is an entire failure.

[The Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, vol. 6 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1896), pp. 273-74]

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

In 1861, the then-21 year old Tchaikovsky – future composer of world-famous works including the ballets Swan Lake and The Nutcracker – was visiting London as part of a tour of Europe. As well as visiting the Crystal Palace and Houses of Parliament, Tchaikovsky walked through the Thames Tunnel, describing it in a letter to his father as ‘so stifling that I almost became sick’! By that time, the Tunnel had gained a reputation as the ‘Hades Hotel’, but Tchaikovsky’s visit shows that it was still a must-see for tourists visiting London.

[Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Letters to His Family. An Autobiography, trans. by Luis Sundkvist (London: Dobson Books, 1981), pp. 7-8]

The Brunel Museum tells the story of the Thames Tunnel, and continues the tradition of welcoming visitors to the Museum. What will you make of it?

We’re planning to include a lot more stories of the people who visited the Thames Tunnel in our Brunel Museum Reinvented project. Donate today to help us tell those stories.