Today marks 180 years since the grand opening of the completed Thames Tunnel on 25th March 1843. As a Victorian tourist attraction it was a huge success, receiving fifty thousand visitors on its opening day. Visitors came from all over the world to marvel at the novelty of walking under a river and it became a recognised London landmark. The Thames Tunnel’s popularity is reflected in the commemorative souvenirs that survive in museum collections. This blog will explore two examples in the Brunel Museum collection, a cotton/linen handkerchief and silk kerchief. They are fascinating products of Victorian souvenir culture and the Thames Tunnel at the height of its popularity.

The printed handkerchief originated as a practical accessory but developed into a souvenir product. While mass-produced, the images printed on commemorative handkerchiefs were ephemeral in nature for a specific and often short-lived market (Schoeser:1988).[1] It was not only handkerchiefs used as souvenirs. In the Brunel Museum collection are a variety of commemorative plates, mugs and peep shows with views of the Thames Tunnel. Contemporary accounts describe the Thames Tunnel as a like a shopping arcade for souvenirs:

“Ladies, in fashionable dresses and with smiling faces, wait within and allow no gentleman to pass without giving him an opportunity to purchase some pretty thing to carry home as a remembrancer of the Thames Tunnel. The Arches are lighted with gas burners, that make it as bright as the sun; and the avenues are always crowded with a moving throng of men, women and children, examining the structure of the Tunnel, or inspecting the fancy wares, toys, &c., displayed by the arch-looking girls of these arches […] It is impossible to pass through without purchasing some curiosity. Most of the articles are labelled – “Bought in the Thames Tunnel” – “a present from the Thames Tunnel”.

–William Allen Drew (1852)[2]

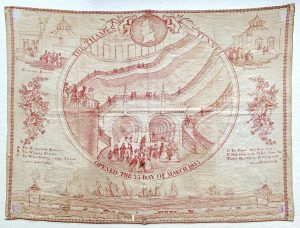

From this description of the interior of the Thames Tunnel, it is wonderful to have surviving souvenirs as a material connection to the experience of the Victorian visitors to the tunnel. One of the Brunel Museum handkerchiefs is cream cotton/linen cloth printed in red: ‘The Thames Tunnel opened the 25th day of March 1843.’ The handkerchief has a compilation of views of the attraction; including Rotherhithe entrance, Wapping entrance, the grand staircase and a labelled diagram of the tunnel. The quality of the handkerchief suggests it was a mass-produced, relatively cheap souvenir for visitors. This can be seen in the red border design, which has been folded into the hem, cutting off the design on the top and bottom. This was a result of the mass-production of handkerchiefs, as they were printed on a continuous length of fabric and then cut and hemmed. By cutting off the design slightly the manufacturer could save fabric, this was worthwhile when printing in large quantities.

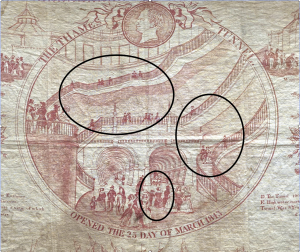

Most of the handkerchief is taken up by a large central illustration of the grand staircase, which was a frequently drawn perspective of the attraction. An illustration by Thomas H. Ellis has a close similarity, with its view of the grand staircase and several identical figures in the scene. To compare these copied figures from the Ellis engraving, I have circled the matching figures on the Brunel Museum handkerchief. It is likely the artist who designed this handkerchief adapted and stitched together several different artists work to create its design, probably to save money and time. It was a known practice for textile manufacturers to copy each others designs as they sought to make profitable products.

The second kerchief is a much more luxurious souvenir. It can be termed as a kerchief, rather than handkerchief due to its much larger size, being about a metre square. It is a red and cream silk kerchief with printed decoration in black, and additional colours of yellow, red and grey. This would have been a more expensive souvenir due to the silk material and the more laborious production process. The additional colours of yellow, red and grey were been applied by hand to the figures in the central illustration. This was termed ‘penciling’ which was the practice of hand painting elements to finish a printed textile design (Greene: 2014).[3]

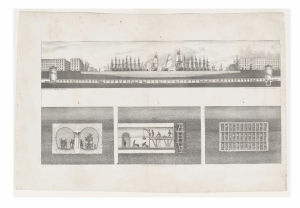

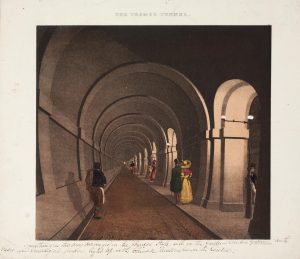

The kerchief has a border design section of the whole tunnel repeated on all four sides and tall ships on all four corners. The illustration of whole tunnel is comparable to one by William Westall that is in the Brunel Museum collection. A similar image can be traced back as early as 1828 in the book ‘Sketches and Memoranda of the Works for the Tunnel under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping’, which contains drawings supplied by Marc Brunel’s workshop. The design also has a central square illustration of the interior of the Thames Tunnel. Like the other handkerchief design, variations of this interior of the tunnel can be seen in many contemporary artworks. After looking through many different versions of the same interior scene, I was delighted to discover the illustration by James D. Harding, which is an exact match for the central illustration on this kerchief. Unlike the other handkerchief that adapted an artist’s illustration, this design seems to have been a true copy of the Harding illustration.

Souvenirs, while mass-produced, signify a personal experience, a material carrier for the memory of an event (Hunt: 2017).[4] For the Thames Tunnel, souvenirs were symbolic of the unique experience had inside the tunnel. Accounts of the experience walking through the Thames Tunnel reflect how unusual the site was for Victorian visitors:

“The sensations experienced as one sits here are very peculiar. A thin brick ceiling over head, covered with a few feet of mud, and many feet of water, with water trickling from the ceiling and through the walls;- and steamers, ships and barges sailing along far above you!- Many bright eyes of timid beauties, and ominous glances of frightened old men, have I seen directed to the walls and ceiling as the crowd hurried along.”

–W. O’Daniel (1859)[5]

It is no wonder after having that experience visitors wanted a souvenir to capture the memory of walking under the River Thames. Souvenir handkerchiefs as practical objects for use or display in the home brought these unusual experiences into familiar, everyday life and domestic interiors. A home decoration guide titled ‘The Drawing Room, Its Decoration and Furniture’ published in 1877 comments on the use of souvenirs to decorate Victorian homes. The writer criticises the “not unfreuquently seen,” home decor of “coal-scuttles ornamented with highly-coloured views of, say, Warwick Castle…screens graced by a representation of ‘Melrose Abbey by Moonlight,’ with a mother-o’-pearl moon” (Orrinsmith: 1877).[6] This suggests a culture of decorating interiors with souvenirs, that the inhabitants likely visited personally.

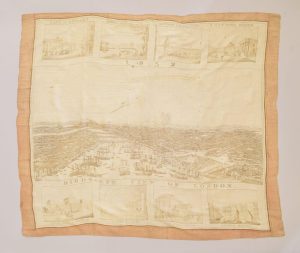

Thames Tunnel souvenirs were not only available within the tunnel. It is clear from extant examples that it became a symbol of London and handkerchiefs with an image of the tunnel were available for tourists to the city more generally. A ‘Birds-eye view of London’ silk handkerchief in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection includes the Thames Tunnel in its eight sights of London. Another example is the spiral game handkerchief of ‘London Sites or All Around St Pauls’ in the Foundling Museum collection that features the Thames Tunnel. In the design the tunnel is described as: “This great excavation is known very well, was planned by the great engineering Brunel” (Foundling Museum: 2022).[7] It is great fun to look at these Victorian tourist attractions and see which ones are still considered so. Moreover, this use of the Thames Tunnel in general London souvenir handkerchiefs reflects its status as a recognisable landmark.

The Brunel Museum collection is a reflection of Victorian consumption and fascination with the engineering marvel of the Thames Tunnel. The contemporary accounts of the tunnel are testament to the unique sensory and emotive experience of travelling under the Thames that visitors wanted to capture with a material souvenir. However, the Thames Tunnel’s popularity as a tourist attraction was short lived. Its reputation diminished over time and was eventually sold to East London Railway in 1869. It was at one point an iconic landmark of London that is now a lost experience. The closest we can get as modern visitors is to visit the surviving tunnel shaft at the Brunel Museum and perhaps buy a tea towel at the shop on the way out!

About the author:

Katie May Anderson has been a volunteer at the Brunel Museum since September 2020. She is currently studying MLitt: Dress and Textile Histories at the University of Glasgow.

This blog was part of a student research project generously funded by the Madeleine Ginsburg grant from the Association of Dress Historians.

References

[1] Schoeser, Mary. Printed Handkerchiefs. London: Museum of London, 1988. https://archive.org/details/printedhandkerch0000scho/mode/2up

[2] Drew, William. Glimpses and Gatherings During a Voyage and Visit to London and the Great Exhibition in the Summer of 1851. Boston: Homan & Manley, 1852. https://archive.org/details/glimpsesgatherin1852drew/page/n3/mode/2up

[3] Greene, Susan W. Wearable Prints, 1760-1860 : History, Materials, and Mechanics. Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2014. https://www.kentstateuniversitypress.com/2011/wearble-prints/

[4] Hunt, Verity. “A Present from the Crystal Palace: Souvenirs of Sydenham, Miniature Views and Material Memory.” In After 1851, 24–. 1st ed. Manchester University Press, 2017. https://academic.oup.com/manchester-scholarship-online/book/19075/chapter-abstract/177489837?redirectedFrom=fulltext

[5] O’Daniel, William. Ins and Outs of London. Philadelphia: S. C. Lamb, 1859. https://archive.org/details/insoutsoflondon00odan

[6] Orrinsmith, Lucy. The Drawing-room; Its Decorations and Furniture. Macmillan and Company, 1877. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_Drawing_room.html?id=g84DAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y

[7] Foundling Museum. “Online Talk | Forgotten Sights of Victorian London – A Pocket Handkerchief Tour” Youtube, 24 June 2022, 53:22, youtube.com/watch?v=Vqm6fbJK5Mc