Though the Thames Tunnel, the world’s first tunnel beneath a navigable river, was an engineering marvel, it was a financial failure. Almost two centuries later, it is a vital north-south rail link as part of London Overground’s Windrush Line. In our latest blog, Mark Kleinman tells the story of how a white elephant became the Windrush Line.

In 1865, the Thames Tunnel was sold to the East London Railway (ELR), and four years later in 1869, steam trains, carrying both people and freight, began their subterranean journeys. Railway services through the Tunnel have continued ever since. But it took almost a century and a half – 141 years to be precise – for the line to become a major part of London’s mass transport system. The delayed coming of age of the East London Line was just fifteen years ago today, on 27 April 2010, when the line became part of the London Overground system, connecting Highbury and Dalston in the North with Crystal Palace, West Croydon, and a little later Clapham Junction, in the South. Around 60,000 people a day now travel through Marc Brunel’s Thames Tunnel, completed almost 200 years ago!

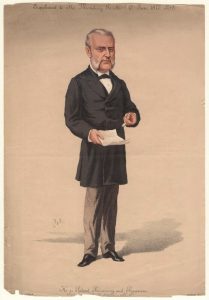

The East London Railway Company never owned its own trains or ran its own services. Instead, it provided a means by which several railway companies, running services either north or south of the Thames, could run through services using the Tunnel. But the ELR always struggled financially. The ELR was initially chaired by William Hawes (1805-85), the former chairman of the Thames Tunnel Company, who was related by marriage to the Brunels. But only 13 years after its inception, in 1878, the Board was re-organised and came under the control of Sir Edward Watkin (1819-1901), a true 19th-century Railway Baron.

Edward Watkin, 1877, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D4644

Watkin was chair or chief executive of several railway companies, including the Metropolitan Railway, the world’s first underground railway, and thought big. He dreamed of running through services from Manchester via London and a Channel tunnel to Paris – and beyond. It wasn’t just dreaming – Watkin succeeded in building about a mile of his tunnel under the Channel in the 1880s. And it was political and military fears about invasion from the Continent, rather than any technical issues that forced him to stop. Did Watkin see the Thames Tunnel as a key part of the infrastructure for his Manchester to Paris railway? There is no clear evidence of this, but it is tempting, and fun, to think so.

The East London Line continued to struggle in the early part of the 20th century. It was late to electrify, and through services from west to south London were gradually withdrawn, leaving a very limited service from Shoreditch via Whitechapel to New Cross. By the time the line was taken over by the London Passenger Transport Board (forerunner of today’s Transport for London) in the early 1930s, it could perhaps be described as an Ugly Duckling compared with its brothers and sisters in the rapidly expanding, and stylish, London Underground. One senior manager, writing to the Vice-Chairman of the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933 talked about ‘being saddled with this additional responsibility,’ referring to the ELR, and an internal report in 1937 described the stations on the line as ‘generally…uninviting and far below the general standards of the Underground…The stations at Rotherhithe, Wapping and Shoreditch are remote from main thoroughfares and the station buildings are poor and unobtrusive.’[1]

An East London Line train entering Surrey Docks, now Surrey Quays, station. Private collection of Jim Connor.

East London Line directional signs at Rotherhithe station. Private collection of Jim Connor.

Over the next 60 years, the Underground network expanded greatly, but the East London Line remained the same, a small stub of a line, coloured Magenta on the tube maps, like its much bigger and more important brother the Metropolitan Line.

Medal issued at the closure of the former East London Line in 2007. Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2007.3

Towards the end of the century and into the beginning of the 21st Century, this began to change. London was expanding, in both people and jobs, particularly in East London, an area that was poorly served by the existing Underground network. More transport infrastructure was needed, and was provided – an extension to the Jubilee Line, the Docklands Light Railway, and later the Elizabeth Line. The Thames Tunnel had been re-lined in the 1990s. Finally, the East London Line could come into its own. Brunel’s wonderful, and still serviceable Thames Tunnel could become the heart not just of a short line from New Cross to Whitechapel, but of a major North-South connection, with large, modern trains running on a tube-like frequency, as part of a re-branded London Overground.

Just as in Hans Christian Anderson’s story, the Ugly Duckling was transformed into a beautiful swan. Re-branded again as the Windrush Line, this vital artery now carries workers and shoppers to Canada Water and Canary Wharf; hipsters and clubbers to Hackney and Shoreditch; and football fans to Arsenal, Millwall, and Crystal Palace. And of course, it brings visitors from across London, and across the world, to the Brunel Museum here in Rotherhithe.

References

[1] Memorandum from C.S. Louch and J.P. Thomas to Frank Pick, 7 July 1933; and anonymous report addressed to managers of the LPTB, the Southern Railway, and the London North Eastern Railway, 12 February 1937, both Transport for London Corporate Archive, London, LT000462/001.