During World War II, the Thames Tunnel was a key transport asset across the Thames. With its strategic location close to the London Docks, it was vulnerable to enemy action. As the tide of war changed in favour of the Allies, neighbouring areas and perhaps the Tunnel itself played a key role in the eventual victory in Europe. Today, on VE Day, Mark Kleinman, Tour Guide and Museum Ambassador at the Brunel Museum looks back at the Thames Tunnel and World War II.

Well before war started on 3 September 1939, both the Government and London Transport had started making preparations for protecting London’s transport network in the event of war. In early 1939, the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) set up an Air Raid Precautions Committee, and activities increased after the ‘Munich Crisis’ of 1938. The LPTB were greatly concerned about the danger of flooding in the tube system if any of the under-river tunnels were breached.[1] The tunnels at risk included those on the Bakerloo Line, on the two branches of the Northern Line – and of course, the Brunels’ Thames Tunnel, then carrying the East London Line, part of the Underground network as well as being a freight route. To prevent such a catastrophe, floodgates were installed in all of these tunnels – including in the Thames Tunnel, at that point nearly 100 years old.

At a meeting of the LPTB Engineering Committee on 27 March 1939, it was agreed to proceed with a scheme to install floodgates in the ‘air shaft’ of the East London Line, on the south side of the Tunnel at Rotherhithe, and also to provide a concrete cover for the shaft.[2] The cost was estimated at around £10,000 – about £557,000 in today’s money. The Ministry of Transport agreed to meet the cost, and an order for the floodgates was placed with Messrs Glenfield & Kennedy of Kilmarnock, Scotland.[3] Tenders for the installation work were sought, and Balfour Beatty were successful in winning the contract.[4]

A year later, in May 1940, the Ministry of Transport sent the LPTB a copy of a report on the inspection of the floodgates by Lieutenant Colonel E. Woodhouse.[5] Colonel Woodhouse’s report, dated 2 May 1940, describes twin gates which can be both electrically operated (with two sources of supply) or hand-operated. He stated that in order to guard against seepage through ‘the old tunnel brickwork, which is not in too good condition,’ both tunnels had been lined with a steel skin for a short distance. Woodhouse recommended that the gates be tested regularly – perhaps three times a week. He realised that this was more complicated for the Thames Tunnel than it was for the tube lines, where those floodgates were closed each night and then opened the following morning, because there was all-night freight traffic on the East London Line, unlike on the District Line or on the tubes. But the freight was only about half-hourly at most, so Woodhouse considered that regular inspection was both possible and necessary.

Woodhouse’s report refers also to the 2 foot 6 inch reinforced concrete cap – now of course supporting the Brunel Museum’s garden! – ‘which was provided over the shaft at the time of the Munich crisis and which was pierced to enable the component parts of the gates to be lowered into position, has been made good and forms the roof of the machinery chamber’.[6] This suggests that the concrete roof was installed first, ahead of the floodgates being ready.

The Norwegian Church, Rotherhithe

May-June 1940 was a critical and immensely difficult time for Great Britain. On 10 May, Germany invaded France, Belgium and the Netherlands. On the same day, Winston Churchill replaced Neville Chamberlain as the British Prime Minister. On 29 May, the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk began. On 7 June, King Haakon VII of Norway, the Norwegian Royal Family, and the Norwegian Government were evacuated from Tromso on the British cruiser HMS Devonshire. In London, a Norwegian Government-in-Exile was set up. In London, the Norwegian Royal Family are said to have often worshipped at St. Olavs, the Norwegian Church in Rotherhithe, and that the King made broadcasts to the Norwegian people from the Church.[7]

Rotherhithe and Wapping suffered very badly, along with the rest of the East End from extensive bombing by the Luftwaffe, especially during the ‘Blitz’, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941. The London Docks were a prime target; one remarkable photograph shows a Heinkel 111 Luftwaffe bomber high above Rotherhithe, almost directly over the tunnel shaft.

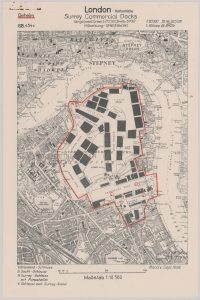

Indeed, the Luftwaffe produced dossiers for its pilots, marked ‘Secret’ (‘Geheim’), which showed targets in Rotherhithe’s Surrey Commercial Docks circled in red.

Target Dossier for London-Rotherhithe, 1938, US National Archives, Washington, D.C., 261887646

Bomb maps make clear the extent of their damage and show the scale of attacks in the area. In one attack, on 11 September 1940, the warehouse adjoining Wapping station was set on fire by high-explosive and incendiary bombs, and the surface buildings of the station were destroyed.[8]

Colour-coded map showing effects of bombing, 1945, via Layers of London (https://www.layersoflondon.org)

The Luftwaffe bombing campaign from 1940 – like the Allied bombing of Germany later – had less effect on civilian morale than had been anticipated before the war[9] — ‘to a remarkable degree, the population of Britain learned to get on with its business amid air bombardment’[10] — but bombing brought homelessness, both temporary and permanent.

‘Children of an eastern suburb of London, who have been made homeless by the random bombs of the Nazi night raiders, waiting outside the wreckage of what was their home’, Sept. 1940, US National Archives, Washington, D.C., 541920

In recognition of the money raised by the people of Bermondsey and Rotherhithe for the war effort, four American B-17 bombers were named after Rotherhithe, Bermondsey or London.[11] ‘Rotherhithe’s Revenge’ in the photo below survived the war; at least one of the other planes was lost with all crew.[12]

‘Rotherhithe’s Revenge’ Bomber, 15 Feb. 1944, US National Archives, Washington, D.C., 204848025

Through the Blitz and through the War, the East London Line (mostly) kept running, but there were of course impacts on services. The minutes of the East London Railway Joint Committee in April 1941 show that finances were affected both by the general decline in passenger traffic in London resulting from the War, and from the closure of the line between 9 September and 3 November 1940.[13] An additional factor was the ‘suspension of services during air raid “alerts” consequent upon the closing of the Rotherhithe floodgates.’[14]

The same set of minutes also shows details of damages to properties, bridges, tunnels and the permanent way along the line, referring to ‘considerable damage’ between September 1940 and February 1941 as a result of enemy action. The minutes of this meeting show that although the line was closed for two months from September 1940, freight trains ran through the Tunnel in order to move coal from the north to the south side of the Thames.

It was a similar story the following year (1941/42). Due to damage from enemy action, the line was closed from 11 May to 9 June, and the Operating Manager reported continuing low level of traffic as a result of evacuations of people and businesses, decreased shipping in the docks, and damage from enemy action.[15]

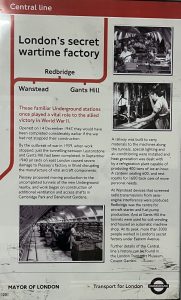

As the war progressed, improvements and innovation in the production to tanks, aircraft and other military equipment was essential to the ability of the Allies to turn the tide. One remarkable example was located in a neighbouring part of East London in a more recent tunnel that had been completed but not opened as part of the Central London Line extension. This unused tunnel was turned into a working factory. Plessey’s factory in Ilford in Essex had been heavily bombed in September and October 1940 during the Blitz. Plessey manufactured equipment that was vital for the war effort, and so a new and safer location was required.[16] They therefore made use of unopened tunnels between Leytonstone and Gants Hill, which were converted into an underground factory in March 1942 at a cost of £500,000, giving Plessey 300,000 sq. ft. of factory space.[17]

The factory produced shell and bomb casings, aircraft parts and radio components.[18] There were around 2,000 workers, mostly women, working in shifts 24 hours a day. The artist and sculptor Frank Dobson painted a striking image of these workers descending an escalator to begin a shift. The single figure on the ‘Up’ escalator is carrying a bicycle – foremen were issued with bicycles to supervise the workers along five miles of tunnel.

Did the Thames Tunnel and the East London Line play a significant role in moving people and freight in the period before and after D-Day in 1944? Some railway historians are clear that it did: ‘during the period leading up to D-Day, vast quantities of armour and ammunition passed to the forward assembly areas through the tunnel’.[19] Mitchell and Smith write similarly: ‘The route carried heavy military traffic in both World Wars.’[20] However, no primary sources are given in either of these books. It does seem plausible that a relatively quiet line that connected with many other lines, e.g. at Whitechapel and at New Cross, was in close proximity to the London Docks, and avoided the congestion (and attention) of central London might have an important role in the logistics of D-Day and the Normandy campaign that followed. But in the absence of direct evidence, this remains speculation.

We do know that another part of Rotherhithe did play a vital role in D-Day, however. The Normandy beaches did not contain any ports or harbours through which the huge quantities of men and material could be safely landed after D-Day. The Allies’ solution was bold and ingenious – to build modular harbours in the UK and take them across and assemble them in situ, just off the Normandy beaches.[21] The artificial harbours would act as breakwaters, giving calmer waters in which troops and equipment could be disembarked onto artificial jetties. One key part of the Mulberry Harbours were the Phoenix caissons – huge blocks of concrete that could float, and which were towed across the Channel to the Normandy beaches. These were built in the South Dock, right next to the Thames Tunnel and what is now the Brunel Museum.

Following D-Day and the Allies’ invasion of Western Europe, Germany responded with its ‘secret weapons’ – V1 and V2 attacks on London. The first V1, a flying bomb, was launched on 13 June 1944, and the first V2, a longer-distance ballistic missile, was launched on 8 September 1944. The attacks continued for months. In all, Rotherhithe and Bermondsey were hit by 30 V1 and seven V2 rockets.[22]

The worst single attack in terms of lives lost happened not far from Rotherhithe in New Cross. On the 25 November 1944, a busy shopping Saturday, a V2 struck the Woolworths store in New Cross Road. 168 people were killed and many more injured.[23]

On 7 May 1945, Germany formally surrendered and the war in Europe was over. The following day, 8 May, was declared Victory in Europe (VE) Day, and a public holiday. There were street parties all over Great Britain, including this one in Southwark Park Road:

A victory party in Southwark, Southwark Archives, London, PB2340. ©Southwark Archives

When the war ended, the Thames Tunnel was just over a century old. Over the course of the 80 years since then, there have been huge changes in the area. The London Docks closed and the whole of the Docklands has been transformed from an industrial and goods-handling centre to a service-based and residential area. But the Thames Tunnel is still here, fulfilling the Brunels’ original vision of connecting London on both sides of the Thames. Indeed more people travel through the Tunnel today, on the Windrush Line, than did at any time in its history.

With thanks to Southwark Archives for generous permission to reproduce an image from their collection.

References

[1] Charles Graves, London Transport at War 1939-45 (London: Oldcastle Books, 1989).

[2] Extract from Minutes of LPTB Engineering Committee (No. 245), 27 March 1939. Archival material cited below is from Transport for London’s Corporate Archives.

[3] East London Railway Joint Committee, 19 April 1939.

[4] Letter to Balfour Beatty from the Office of the Chief Engineer (Civil) LPTB, 12 May 1939.

[5] Letter to Secretary of the LPTB from Ministry of Transport, 4 May 1940.

[6] Report by E. Woodhouse ‘East London Railway Rotherhithe Floodgate,’ 2 May 1940.

[7] London Remembers https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/king-olav-v-of-norway; The Bridge December 2009/January 2010 https://web.archive.org/web/20130928095639/http://southwark.anglican.org/thebridge/0912/0912p8.pdf

[8] See Charles Lee, The East London Line and the Thames Tunnel: A brief history (London: London Transport, 1976).

[9] R.A.C.Parker, The Second World War, A Short History, chapter 10.

[10] M.Hastings, All Hell Let Loose, p.93

[11] https://bravescout.com/war-effort/bermondsey-b-17-aircraft/

[12] https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/aircraft/42-39895

[13] ELRJC Minutes, 2 April 1941, item 4231.

[14] ELRJC Minutes 2 April 1941, Appendix A.

[15] ELRJC Minutes, 15 April 1942, Appendix A.

[16] See London Transport Museum ‘Plessey: the tube’s secret wartime underground factory’.

[17] See IanVisits ‘70th anniversary of an aircraft factory hidden in a tube tunnel’ https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/70th-anniversary-of-an-aircraft-factory-hidden-in-a-tube-tunnel-6408/

[18] https://www.jrsaville.co.uk/wanstead_plessey.htm

[19] Lee, The East London Line and the Thames Tunnel.

[20] V. Mitchell and K. Smith, East London Line (Midhurst: Middleton Press, 1996).

[21] A. Byrnes, ‘A Rotherhithe Blog: Mulberry Harbours at Rotherhithe’s South Dock in the Second World War’; and ‘Brave Scout: WW2 in Bermondsey – Mulberry Harbours Construction’.

[22] See https://www.flyingbombsandrockets.com/V1_summary_se16.html

[23] Zoe Melabianaki and Dominic Hewitt, ’80 Years On: the V Weapon Attacks on Britain’, Imperial War Museum Blog, 10 Oct. 2024.