In our latest blog, Collections Volunteer Arran Saunders provides new insights into the Thames Tunnel Designs acquired by the Museum in 2017, following a period of cataloguing and research. Calling into question received ideas about artistic attribution and highlighting new archival discoveries about the production of the Designs and their purpose, the project has developed a far greater understanding of the Designs and unlocked new interpretations of both individual images and the collection as a whole.

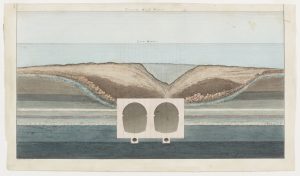

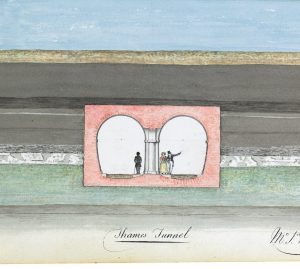

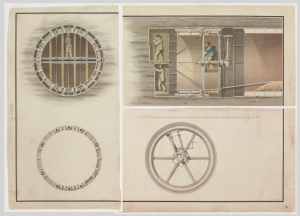

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.23. Watercolour of Shaft and Cross-Section of Tunnel. Probably Joseph Pinchback, 1826.

To engineers like Marc Brunel in the early 1800s, being the first to build a tunnel under the Thames was an alluring prospect. Not only had it never been done before, following two failed attempts by Ralph Dodd and Robert Vazie in 1799 and 1807 respectively, but it promised a practical solution to over-congestion on the river benefiting the public, trade, and even the military. This guaranteed considerable public interest in the project that the Thames Tunnel Company quickly took advantage of: perhaps more visual media was produced than any other engineering project during and after the almost two decades it took to build the Thames Tunnel.[1]

This mass publicisation proved crucial to the Tunnel’s eventual success, be it through securing funding or cultivating public interest.[2] A collection of 33 designs for the Tunnel, acquired by the Brunel Museum in 2017 and which date from before Brunel’s patent in 1818 to after the Tunnel’s completion in 1843, offers a new opportunity to contextualise and better understand the role visual materials played in the project. By taking a closer look at original designs side-by-side, we can spot details, draw parallels, and identify differences that reveal clues as to their dating, authorship, intended audiences, material history, and purpose.

When were they produced?

The designs were predominantly produced between 1818 and 1837. The earliest designs therefore date from the period of Marc Brunel’s patent Forming Drifts and Tunnels Underground which was submitted in January 1818, and they continue right throughout the first round of tunnelling and hiatus years of 1828 to 1836 caused by flooding in the Tunnel. Thanks to this, the collection provides a unique visual chronology of how Brunel’s tunnel designs evolved, how funding challenges and repeated floods shaped the project, and how the Tunnel was ultimately carved out from beneath the Thames.[3]

Who made them?

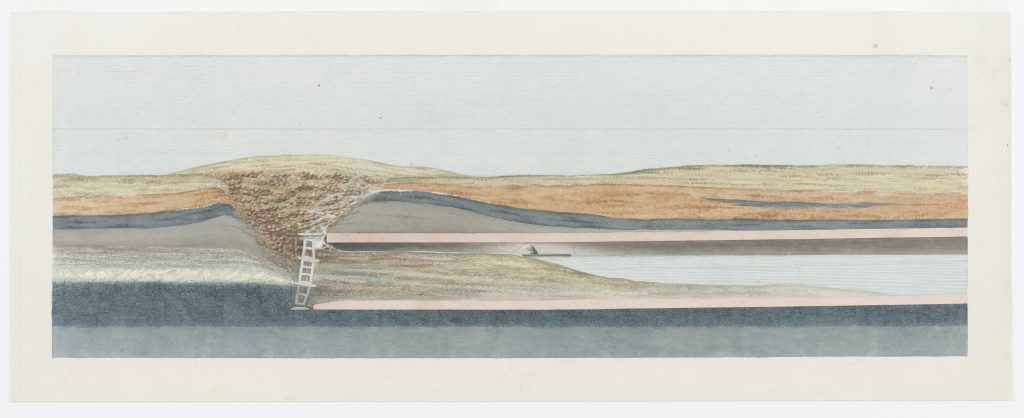

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.16. Cross-Section of the Thames Tunnel and Displaced Ground. Joseph Pinchback, 1827.

The collection is composed of a variety of watercolours, drawings, and sketches of the Thames Tunnel at various stages of completion. The first thing this variety offers is an insight into the engineers and draughtsmen who produced them.

We know from Marc Brunel’s diaries that he frequently worked on designs for the Tunnel, albeit not necessarily in the form of drawing or painting, and had support from several employees who were given varying degrees of attribution.[4] Key among them is Joseph Pinchback, Brunel’s chief mechanical draughtsman. Several pieces in the collection are signed by him or share subtle visual similarities implying at least some level of involvement. There are also pieces produced by others, such as Richard Beamish, resident engineer at the Tunnel, or William Warrington, an engraver and printer who worked with the Thames Tunnel Company.

Interestingly, the collection lacks any pieces directly attributable to some of the more junior draughtsmen, such as Henry Law and Frederick Finlay. There are two possible explanations for this. The first is that the designs were often worked on by several people, as we learn from the diaries of one of Brunel’s employees, Gilbert Blount, who worked at the Tunnel as superintendent from 1841-42. On 7 March 1842, Blount wrote that:

[Marc Brunel] told me to put in the elevation of Rotherhithe shaft to [Joseph] Charlier’s drawing. I washed out the old elevation put in by [Joseph] Pinchback.[5]

This diary entry even shows, perhaps surprisingly, that the Thames Tunnel Company’s Clerk, Joseph Charlier, was involved in the designs. Other diary entries indicate that drawings by Blount and others were subsequently checked and signed by Marc Brunel.[6] Apart from showing that a single design may have had many versions throughout its life, and emphasising that Brunel’s signature is not evidence of his authorship, it also helps us understand why some of the most polished (and perhaps highly-iterated) designs do not have any signature or obvious author.

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2001.2. Watercolour of the Thames Tunnel, signed by Marc Brunel, 1835 (detail)

This finding has even enabled us to question previous assumptions made about the particularly well-known watercolour of the Tunnel and river above, acquired in 2001 and formerly assumed to be the work of Marc Brunel alone due to his signature appearing on the image.

The second reason could be due to working practises at the time.[7] Many drawings that junior draughtsmen created would be focused on smaller, less outwardly attractive elements of the project more useful internally than for any sort of public viewing. Compared to the visual appeal and grandeur of so many of the pieces that have survived the past two centuries, it is not hard to imagine why fewer of these were preserved or promoted at the time.

Certain designs in this collection also bear striking resemblance to those that appear in Thames Tunnel guidebooks (which were re-published more than a dozen times over 35 years), broadsheets, and souvenir prints. That the same design was published in all these different forms further implies close partnerships between engineers, draughtsmen, and engravers, and makes it harder to suggest sole authorship.

While all this certainly complicates attributing individual drawings, it is symptomatic of the field of engineering undergoing significant changes in the early to mid-1800s. A relationship emerged between the layman, for whom these designs were a predominant and effective way of informing themselves in a rapidly evolving world, and engineers like Marc Brunel, for whom they were an invaluable and necessary promotional tool.[8] The role of the draughtsman was at the core of this relationship.

What were they used for?

The late 1700s through to the mid-1800s saw shifts in the way engineers presented their work, as more technical drawings gained popularity in both the workplace and public domain. Frances Robertson has identified three distinct types of drawing emerging from this period: working designs, technical drawings, and presentation pieces.[9] Each has a set of distinct visual characteristics that are inherent to their purpose and help us better understand how they were used.

In the workplace

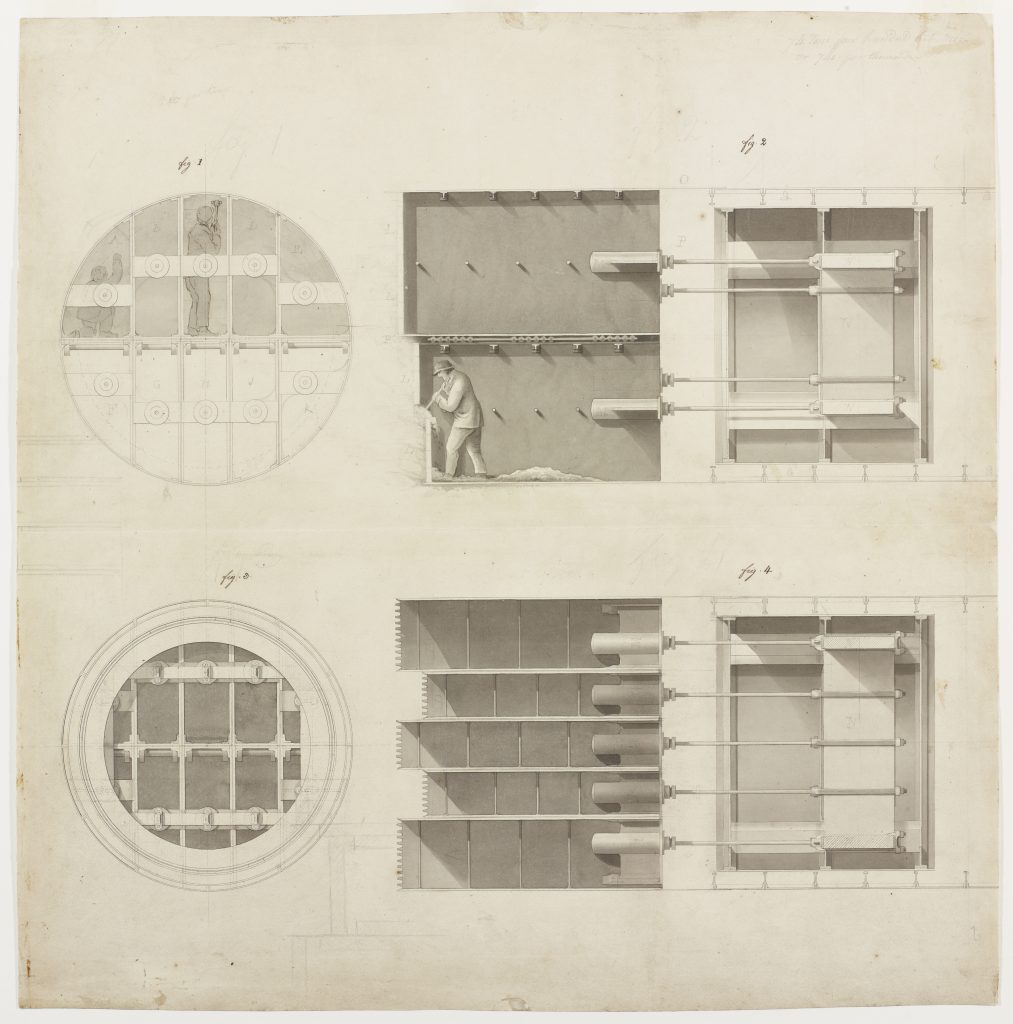

Engineers like Marc Brunel used technical drawings to propose new designs and bring them to life in the workplace. While few specifically technical drawings have made their way into the Museum’s collection, we can see many of their characteristics in the patent drawings such as the below:

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.10. Four view of the Tunnelling Shield, probably by Marc Brunel, 1818

Most obvious here is the lack of colour, but the image above also omits the pictorial shadowing seen in the others and all are views of the shield difficult to understand without some engineering knowledge. This makes perfect sense considering their intention was to translate the technicalities of a new design into a patent, not bring them into public discourse.

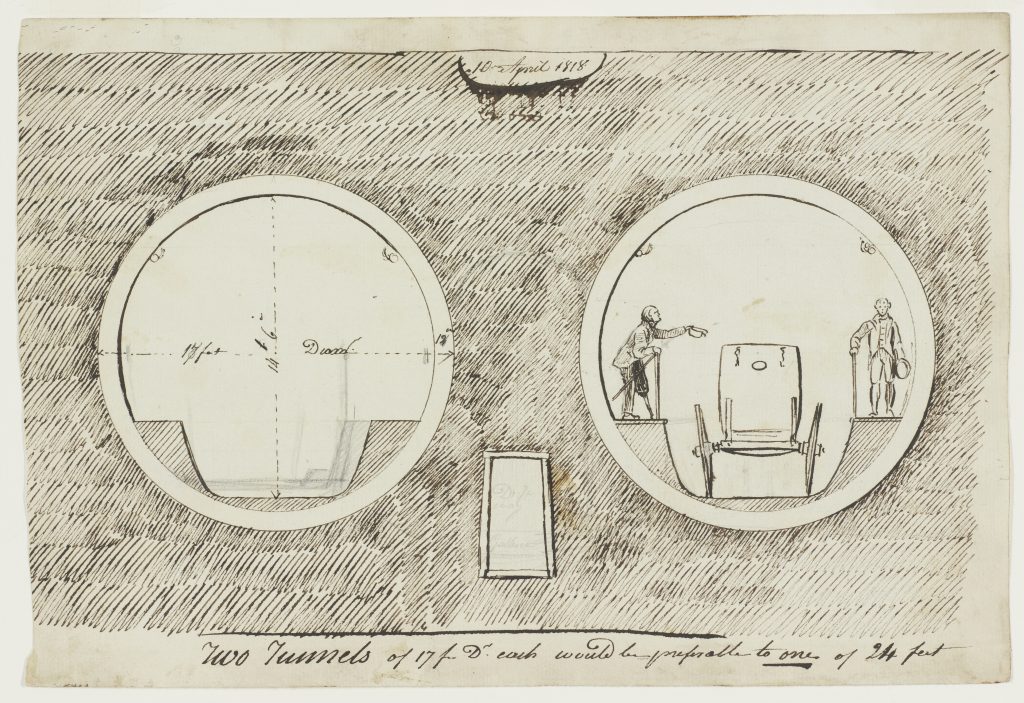

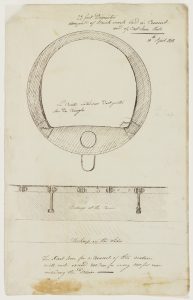

To sketch ideas and events

The Museum’s collection contains several working sketches that provide a snapshot into the ‘mind’s eye’ of key individuals behind the Tunnel project. For example, Marc Brunel’s drawings of a circular tunnel dated April 1818 (above, and left) offer a great insight into the progression of the Tunnel’s design. While care has been taken in these pieces to draw a geometric circle, it is accompanied by rough shading and loose annotations in both French and English that suggest it may have been revisited at a later date and perhaps shared with a French speaker.

Meanwhile, William Hawes’ illustration of the poling boards after a flood (below) shows a preoccupation with recording and presumably sharing the effects of key events, and the status of recovery efforts.

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.4. Sketch of damage to the Thames Tunnel following flooding. William Hawes, probably 1828.

To share to the public

Making up the bulk of the Museum’s collection, presentation drawings intended for public consumption are far more polished pieces of work. Still retaining the central aesthetic of a technical drawing, they employ watercolours and pictorial rendering to give them an artistic flair, distilling complex designs into something more approachable to non-specialist audiences.

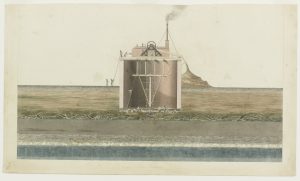

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.7 Watercolour of the Rotherhithe Shaft. Probably Joseph Pinchback, 1824/5.

For example, we know these designs were shown to shareholders and other important individuals who were connected, but not directly involved, with the Tunnel. Blount noted in his diary on 1 March 1842 that:

[Henry] Law and I finished repairing long section of Tunnel which was sent to Town for the annual meeting of the shareholders held this day[10]

These designs of the Tunnel undoubtedly played a crucial role in the process of securing funding from high-profile individuals and investors, and were almost certainly shown to ambassadors, royalty, and other such special visitors. For example, in 1834, Marc Brunel showed drawings and models to members of the Royal Society on a visit to the suspended Tunnel works.[11] At the same time, records indicate that these images were periodically shown to the wider public. For example, on 2 March 1825, at the ceremony of the commencement of work on the Tunnel, Marc Brunel had shown a curious crowd of local Rotherhithe residents designs of what the project would entail.[12]

Even many years later, long after the Tunnel was completed, these drawings were in use to explain to wider audiences how it had been achieved. In 1884, Henry Law gave evidence before a parliamentary committee and showed watercolours to explain the methodology.[13] Law used this specific piece in particular, a depiction of the investigation of damage following the first flood of 18 May 1827:

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.17. Side View of the Flooded Thames Tunnel. Possibly by Joseph Pinchback, 1827

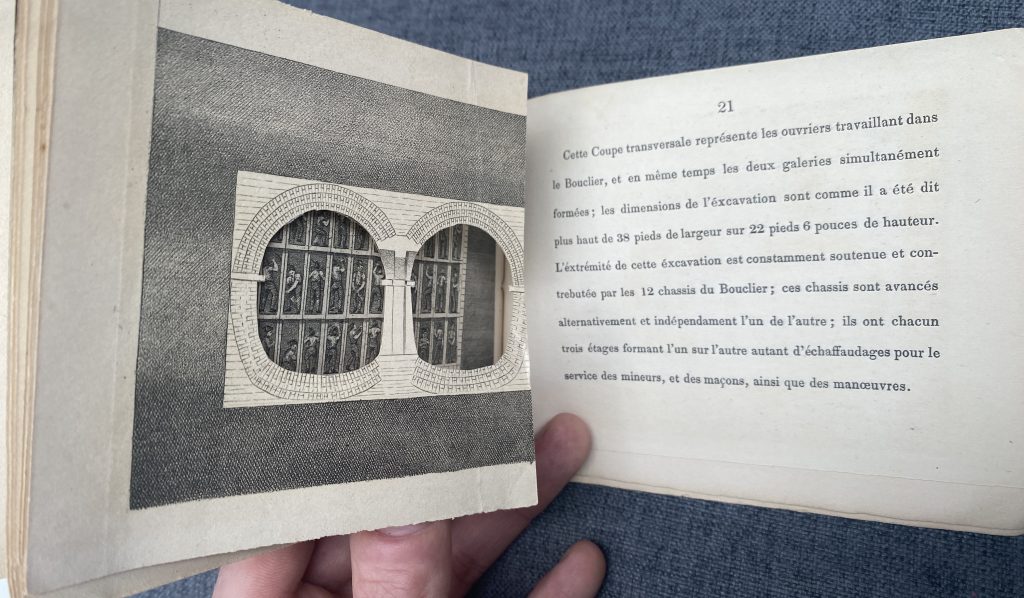

But perhaps the clearest example of a presentation piece in the collection is the cross-sectional view of the tunnelling shield with a brickwork overlay (LDBRU:2017.9). This design was clearly made to be interactive and demonstrate how the tunnelling process was being carried out.

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.9. Section of Tunnel (with Overlay), probably by Joseph Pinchback, around 1827.

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.9. Section of Tunnel (without Overlay), probably by Joseph Pinchback, around 1827.

The interactive overlay must have been considered to work well, since guide books were printed with a very similar overlay which could be lifted to reveal the Shield:

To engage the public through promotional media

A common thread running through all of these pieces is their reproducibility: their clean geometric lines and pictorial rendering translated extremely well into engraved plates for mass printing. Within the collection there are several examples of where presentation pieces have been engraved and then published across guide books, souvenir prints, industry publications, and broadsheets (see e.g. the below).

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.3(a). Watercolour of one frame of the Shield. Richard Beamish, c. 1835.

Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.3(b). Print of one frame of the Shield. William Warrington, after 1835.

A concoction of previously failed attempts, outright difficulty, and promised public benefits meant that the Tunnel aroused considerable public curiosity. These images were a great way for Marc Brunel to not only develop his reputation as one of Britain’s best engineers, but to sustain public interest as the years passed.[14] To this end, the Thames Tunnel Company was clearly aware of how important it was to keep the public’s support and placed significant emphasis on the public benefits the Tunnel would bring.[15] For the first round of funding, which came in the form of share capital, the images would have been useful visual references and were likely shown in places such as the first public general meeting on 19 February 1824.

In 1828, as the Tunnel was bricked up following a major flood, a second round of funding was announced in the form of debentures and annuities to be repaid with tolls charged to visitors to the Tunnel. Given that the importance of attracting visitors to the Tunnel therefore only increased, it’s easy to see why the Tunnel Company doubled-down on mass media— in which, perhaps surprisingly, they did not shy away from disasters like the floods, but instead used them as a talking point and an opportunity for a show of heroism in the face of adversity (e.g. the image of Richard Beamish scrambling amongst the debris in the flooded tunnel, seen above).

What do we know about their material history?

Over the past two centuries, the images have made quite the journey before being acquired by the Brunel Museum. It is clear that many, now catalogued as individual images, were cut from larger sheets. We have been able to reconstruct one sheet digitally:

Digital composite reconstruction of a now-fragmented sheet, made up of Brunel Museum, London, LDBRU:2017.5, LDBRU:2017.19, and LDBRU:2017.20.

This reconstruction, and the possibility of further reconstructions in future, opens up new interpretative possibilities.

A selection of archival material related to the 1984 exhibition of the images held at Brunel University Library, kindly donated to the Brunel Museum in 2025 by Liz Chapman MBE.

While it is unclear why the sheets were cut, we do know that they were kept in a series of three sketchbooks since the 1800s and had been cut to fit the books. Research for this project has further discovered that, in 1984, in preparation for an exhibition at Brunel University Library these images were removed from the sketchbooks in which they had been kept, underwent conservation treatments and were then mounted by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

They underwent further conservation after being acquired by the Brunel Museum, funded by the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust.

Conclusion

Above all, the Tunnel Company’s pioneering use of illustrations reflects the evolving field of engineering in the early to mid 1800s. On the one hand we have a collection of artistic illustrations which we now know were put together by a team of draughtsmen in a workshop-like structure —in spite of many having been long-believed to be done by Brunel’s own hand—and, on the other, a highly-successful draughtsman, Joseph Pinchback, being awarded an individual bronze Telford medal in 1838 for his images of the tunnelling shield and overall ‘beauty of the drawings.’[16]

By the time the Tunnel had opened, draughtsmen had solidified their specialist role in the industry distinct from architects, designers, and engineers, and been recognised for their contributions. The public-facing uses of these watercolours proved instrumental in the eventual success of the Tunnel, right from the initial phase of developing interest and public support through to using them as promotional tools to attract visitors and sustain funding.

References

[1] Julia Elton, ‘The Tunnel in Print,’ in Michael M. Chrimes, Julia Elton, John May, and Timothy Millett, The Triumphant Bore: A Celebration of Marc Brunel’s Thames Tunnel (London: Institution of Civil Engineers, 1993), pp. 25-32 (p. 25).

[2] Ibid.

[3] The comparable collection (TT/DRA/1-4) held at the Institution of Civil Engineers [ICE], London, contains many more technical drawings of use or interest to predominantly engineers.

[4] See e.g. ICE TT/BD/2, fol. 15r (25 March 1826): ‘Engaged in the early part on the Drawing for the improvements of some parts of the Shield’

[5] Brunel University Library Special Collections, London, BLT/2/1, fols 10v-11r (7 March 1842).

[6] BLT/2/1, fol. 8v (23 Feb 1842): ‘Finished the drawing of shoes etc which was signed by Sir Isambart [i.e. Marc Brunel] and sent’

[7] Frances Robertson, ‘Ruling the Line: Learning to Draw in the First Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (PhD Thesis, Glasgow School of Art, 2011), p. 24.

[8] Robertson, ‘Ruling the Line,’ pp. 93-94.

[9] Ibid, pp. 93-94.

[10] BLT/2/1, fols 9r-9v (1 Mar 1842).

[11] ‘The Thames Tunnel,’ The Guardian, 31 March 1834, p. 3.

[12] ‘The Thames Tunnel,’ The Times, 3 March 1825, p. 3.

[13] Reports from the Select Committee on Metropolitan Board of Works (Thames Crossings) Bill, &c.; Together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendix (London: Henry Hansard and Son, 1884), p. 118 (Evidence of 22 May 1884).

[14] Robertson, ‘Ruling the Line,’ p. 134

[15] See e.g., with suggestive subtitle, The Origin, Progress, and Present State of the Thames Tunnel; and the Advantages Likely to Accrue from it, both to the Proprietors and to the Public, 4th edn. (London: Effingham Wilson, 1827).

[16] Robertson, ‘Ruling the Line,’ p. 164; The Mechanic’s Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal and Gazette, vol. 30 (London: W.A. Robertson, 1839), p. 333.