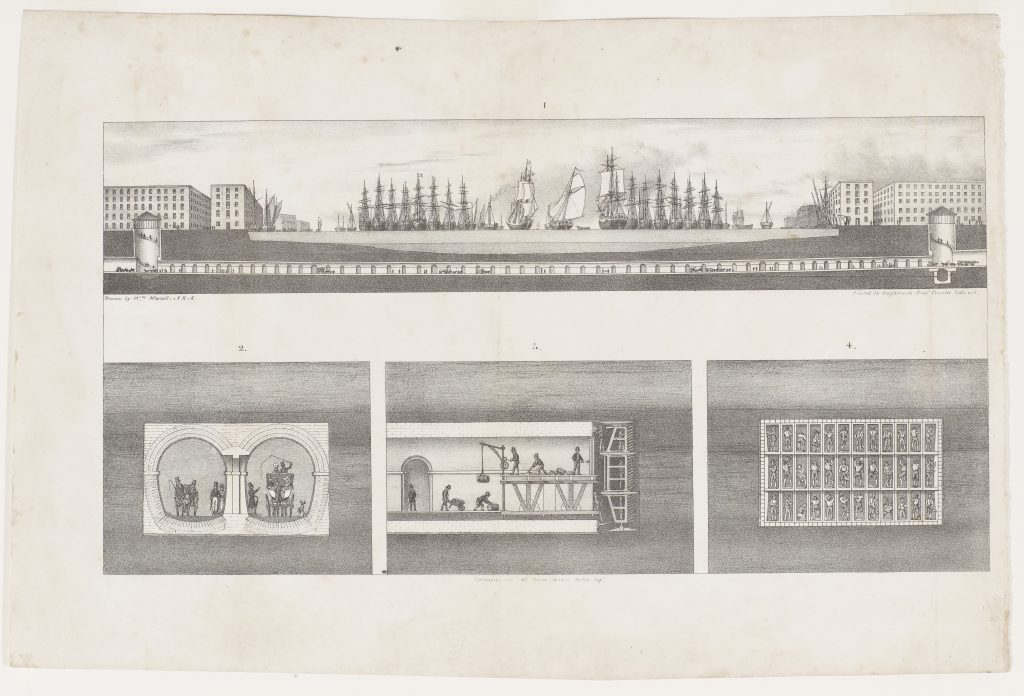

This group of four lithographic drawings was drawn by William Westall (signed Wm. Westall A.R.A.) in 1827. Published both individually and separately, they were an important tool for promoting one of the most complex and challenging engineering projects ever undertaken.

The uppermost drawing (no. 1) envisions the Tunnel in its entirety when completed, something which would not occur until 16 years later in 1843. Later versions of this drawing published after September 1835 would show the Tunnel’s current progress. On the lower left (no. 2) is a cross-sectional view of the Tunnel in use by pedestrians and horse-drawn carts. The idea of pedestrians or horses crossing the Thames without walking over a bridge would have been a very novel concept, and is undoubtedly a large part of why the project attracted so much public interest. These drawings also serve as an interesting reminder of the Tunnel’s troubled construction: when it finally opened, there would be no horses or carriages passing through as the land required to make entry and exit ramps had not been purchased following several bouts of financial difficulties.

In the lower middle (no. 3) is a drawing that bears several similarities to LDBRU:2017.8, albeit with miners at work. This piece shows clearly the process of excavating the earth and laying the brickwork, reminiscent of the teredo navalis shipworm which inspired Brunel’s design. Lastly, the lower right (no. 4) shows a cross-sectional view of the tunnelling shield with miners in their individual sections. The shield itself was central to the entire project and was another key point of interest.

Visitors to the Tunnel were numerous and in some regards shaped its legacy. Beginning in 1827, these four drawings were widely reproduced in all editions of the tunnel guidebooks named Sketches Of The Works For The Tunnel Under The Thames, From Rotherhithe To Wapping. These booklets were sold as souvenirs at the Tunnel for a price of one shilling, updated and published over a dozen times, and translated into five languages in order to capitalise on interest in the Tunnel’s construction and Brunel’s work. They also included fold-out pages, and the image of the tunnelling shield came with an overlay showing the brickwork.

Each drawing provides a unique perspective on the Tunnel and distils the project into very visually-comprehensible terms for a lay audience. The wide longitudinal view of the Tunnel was also printed on a silk kerchief sold as a souvenir of the Thames Tunnel. The deliberate approach of appealing to the general public is characteristic of many engineering projects in this period and structures many of the images which Brunel and the Thames Tunnel Company published.

Throughout the Industrial Revolution (circa 1750-1900), technical drawings became popular as an effective way of communicating designs and functionality. However, by the early 1800s, their importance in shaping public perception and bringing engineering to the masses was beginning to be understood. Drawings for the workplace would have included many more technical details, but pieces like these were made for a very different purpose. They favoured a more artistic approach with pictorialist lighting, contained no technical annotations, and were easily reproduced.

Brunel and the Thames Tunnel Company directors clearly understood and appreciated the importance of public perception to a project so ambitious yet prone to disaster as this one. Appealing to the public would be a way of not only growing an audience, but developing Brunel’s reputation and of giving the Tunnel the best possible chance of success.

If you’d like a print of the artwork displayed above, you can purchase one from the ArtUK online shop.